Carbon-rich exoplanets may be made of diamonds

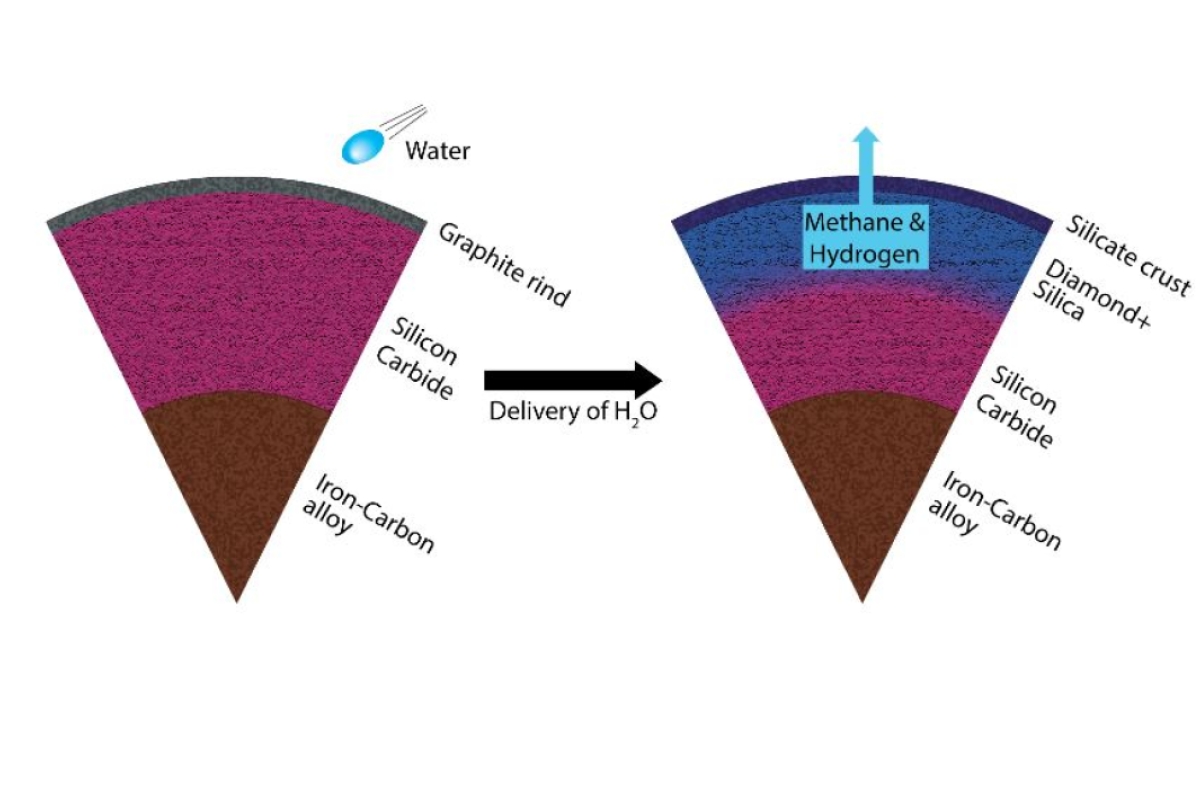

Illustration of a carbon-rich planet with diamond and silica as main minerals. Water can convert a carbide planet into a diamond-rich planet. In the interior, the main minerals would be diamond and silica (a layer with crystals in the illustration). The core (dark blue) might be iron-carbon alloy. Credit: Shim/ASU/Vecteezy

Editor’s note: This story is being highlighted in ASU Now’s year in review. Read more top stories from 2020.

As missions like NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, TESS and Kepler continue to provide insights into the properties of exoplanets (planets around other stars), scientists are increasingly able to piece together what these planets look like, what they are made of and if they could be habitable or even inhabited.

In a new study published recently in The Planetary Science Journal, a team of researchers from Arizona State University and the University of Chicago have determined that some carbon-rich exoplanets, given the right circumstances, could be made of diamonds and silica.

“These exoplanets are unlike anything in our solar system,” said lead author Harrison Allen-Sutter of ASU’s School of Earth and Space Exploration.

Diamond exoplanet formation

When stars and planets are formed, they do so from the same cloud of gas, so their bulk compositions are similar. A star with a lower carbon-to-oxygen ratio will have planets like Earth, comprised of silicates and oxides with a very small diamond content (Earth’s diamond content is about 0.001%).

But exoplanets around stars with a higher carbon-to-oxygen ratio than our sun are more likely to be carbon-rich. Allen-Sutter and co-authors Emily Garhart, Kurt Leinenweber and Dan Shim of ASU, with Vitali Prakapenka and Eran Greenberg of the University of Chicago, hypothesized that these carbon-rich exoplanets could convert to diamond and silicate, if water (which is abundant in the universe) were present, creating a diamond-rich composition.

Diamond-anvils and X-rays

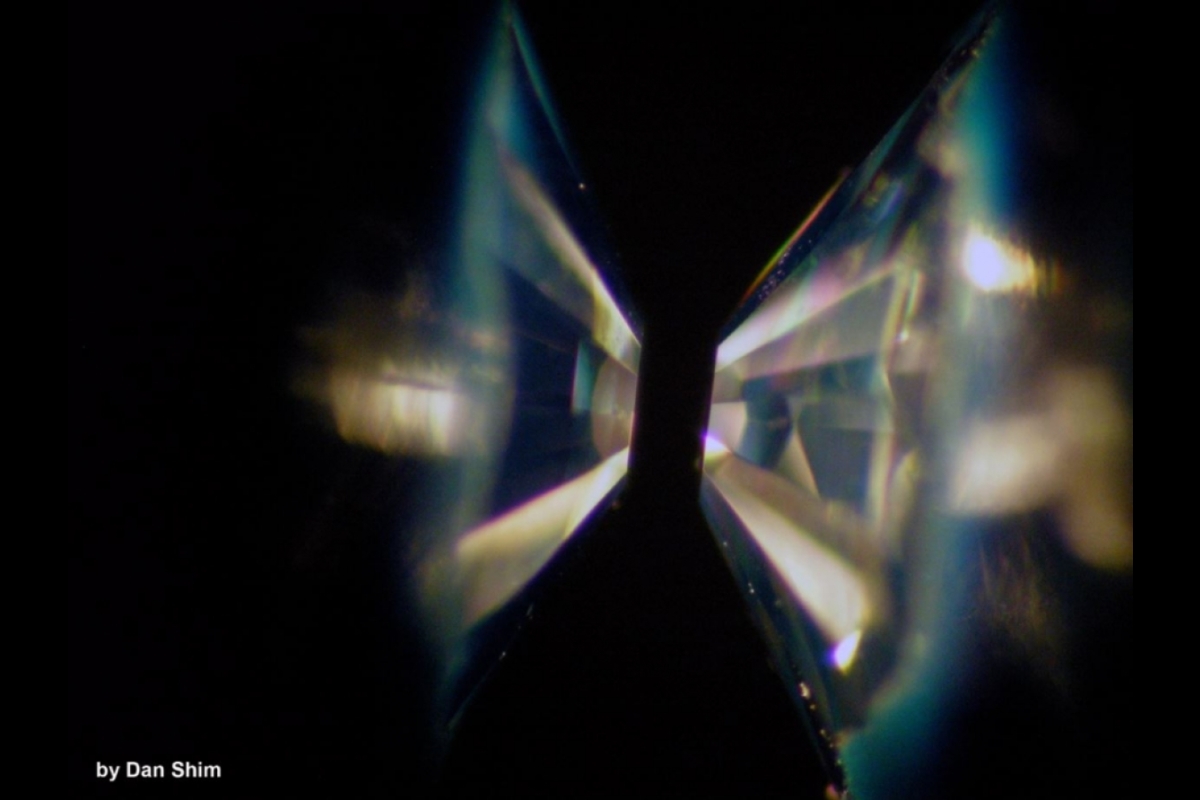

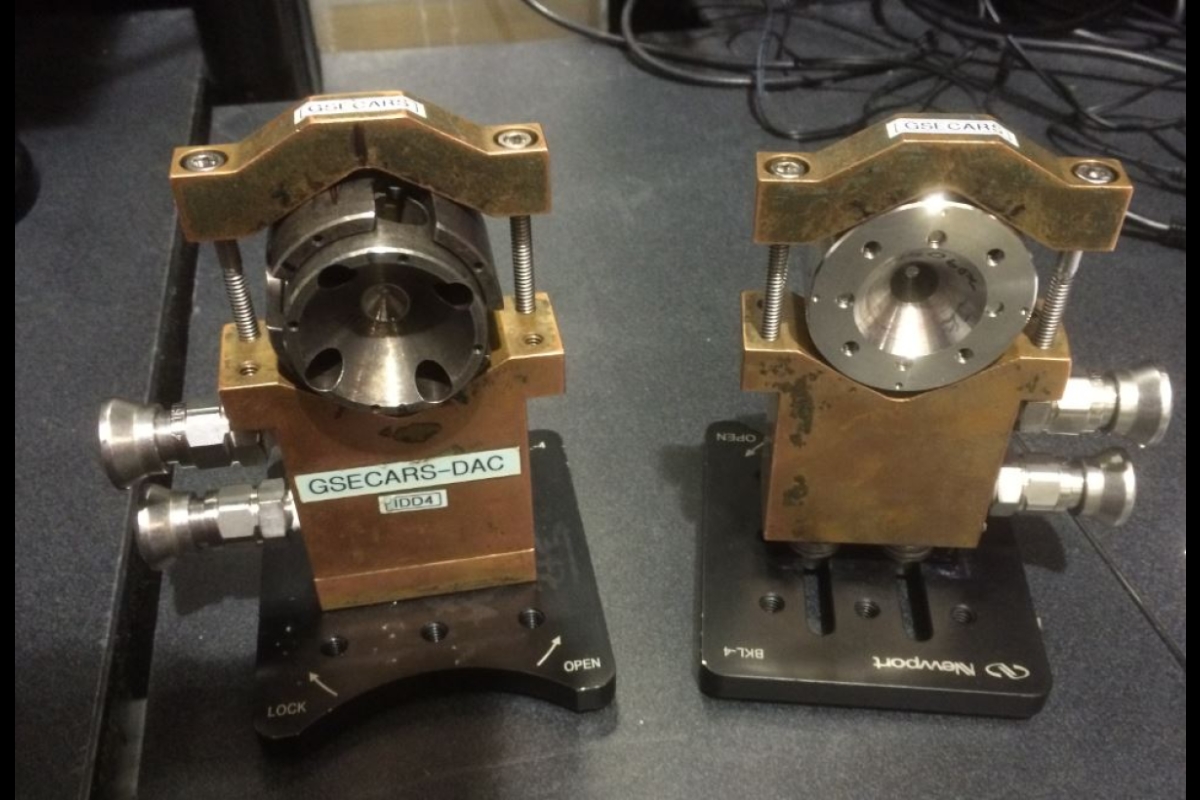

To test this hypothesis, the research team needed to mimic the interior of carbide exoplanets using high heat and high pressure. To do so, they used high pressure diamond-anvil cells at co-author Shim’s Lab for Earth and Planetary Materials.

First, they immersed silicon carbide in water and compressed the sample between diamonds to a very high pressure. Then, to monitor the reaction between silicon carbide and water, they conducted laser heating at the Argonne National Laboratory in Illinois, taking X-ray measurements while the laser heated the sample at high pressures.

As they predicted, with high heat and pressure, the silicon carbide reacted with water and turned into diamonds and silica.

Habitability and inhabitability

So far, we have not found life on other planets, but the search continues. Planetary scientists and astrobiologists are using sophisticated instruments in space and on Earth to find planets with the right properties and the right location around their stars where life could exist.

For carbon-rich planets that are the focus of this study, however, they likely do not have the properties needed for life.

While Earth is geologically active (an indicator of habitability), the results of this study show that carbon-rich planets are too hard to be geologically active and this lack of geologic activity may make atmospheric composition uninhabitable. Atmospheres are critical for life as it provides us with air to breathe, protection from the harsh environment of space and even pressure to allow for liquid water.

“Regardless of habitability, this is one additional step in helping us understand and characterize our ever-increasing and improving observations of exoplanets,” said Allen-Sutter. “The more we learn, the better we’ll be able to interpret new data from upcoming future missions like the James Webb Space Telescope and the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope to understand the worlds beyond our own solar system.”

More Science and technology

Breakthrough copper alloy achieves unprecedented high-temperature performance

A team of researchers from Arizona State University, the U.S. Army Research Laboratory, Lehigh University and Louisiana State…

4 ASU researchers named senior members of the National Academy of Inventors

The National Academy of Inventors recently named four Arizona State University researchers as senior members to the prestigious…

Transforming Arizona’s highways for a smoother drive

Imagine you’re driving down a smooth stretch of road. Your tires have firm traction. There are no potholes you need to swerve to…