Ancient rocks provide clues to Earth’s early history

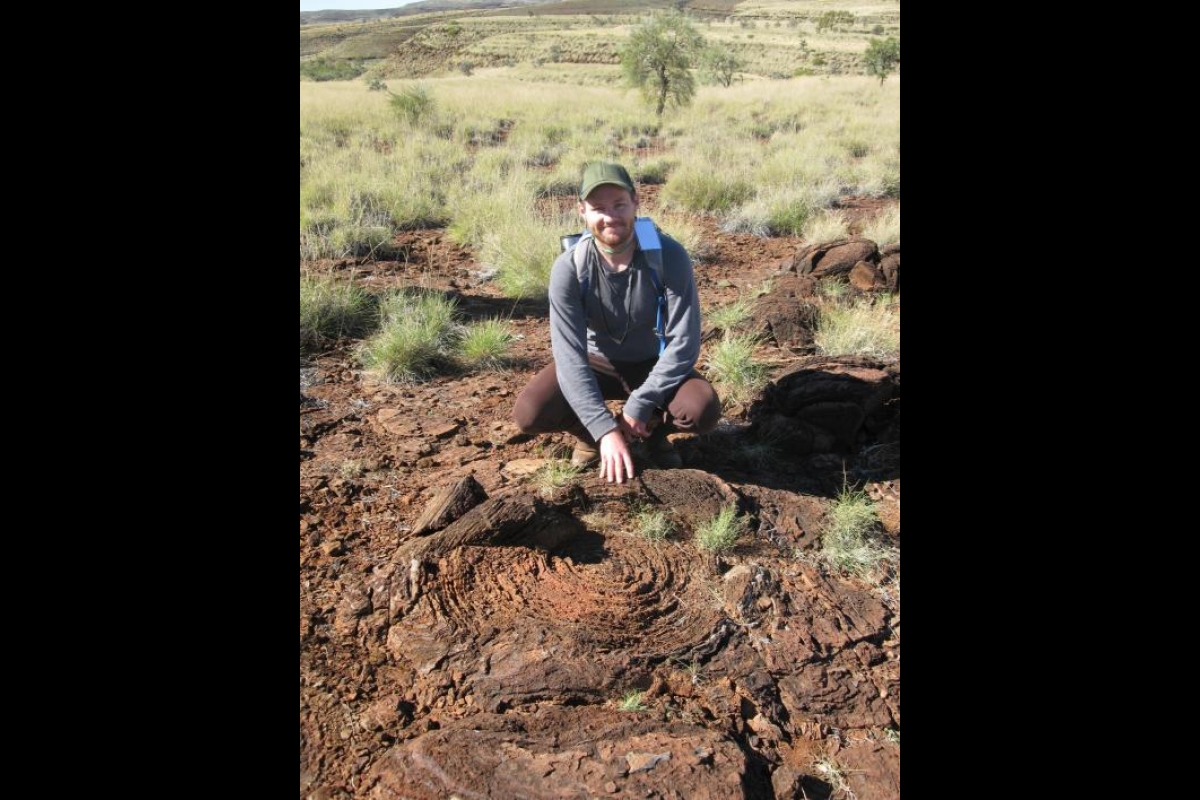

Stromatolite in Shark Bay, Western Australia. These stromatolites are thought to be some of the most ancient forms of life on Earth and are comprised of organisms that probably contributed to the O2 scientists are inferring existed on ancient Earth (i.e., cyanobacteria). Credit: Ariel Anbar, ASU

Oxygen in the form of the oxygen molecule (O2), produced by plants and vital for animals, is thankfully abundant in Earth’s atmosphere and oceans. Researchers studying the history of O2 on Earth, however, know that it was relatively scarce for much of our planet’s 4.6 billion-year existence.

So when, and in what environments, did O2 begin to build up on Earth?

By studying ancient rocks, researchers have determined that sometime between 2.5 and 2.3 billion years ago, Earth underwent what scientists call the “Great Oxidation Event” or “GOE” for short. O2 first accumulated in Earth’s atmosphere at this time and has been present ever since.

Through numerous studies in this field of research, however, evidence has emerged that there were minor amounts of O2 in small areas of Earth’s ancient shallow oceans before the GOE. And in a study published recently in the journal Nature Geoscience, a research team led by scientists at Arizona State University has provided compelling evidence for significant ocean oxygenation before the GOE, on a larger scale and to greater depths than previously recognized.

For this study, the team targeted a set of 2.5 billion-year-old marine sedimentary rocks from Western Australia known as the Mt. McRae Shale.

“These rocks were perfect for our study because they were shown previously to have been deposited during an anomalous oxygenation episode before the Great Oxidation Event,” said lead author Chadlin Ostrander, of ASU’s School of Earth and Space Exploration.

Shales are sedimentary rocks that were, at some time in Earth’s past, deposited on the sea floor of ancient oceans. In some cases, these shales contain the chemical fingerprints of the ancient oceans they were deposited in.

For this research, Ostrander dissolved shale samples and separated elements of interest in a clean lab, then measured isotopic compositions on a mass spectrometer. This process was completed with the help of co-authors Sune Nielsen at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (Massachusetts); Jeremy Owens at Florida State University; Brian Kendall at the University of Waterloo (Ontario, Canada); scientists Gwyneth Gordon and Stephen Romaniello of ASU’s School of Earth and Space Exploration; and Ariel Anbar of ASU’s School of Earth and Space Exploration and School of Molecular Sciences. Data collection took over a year and utilized facilities at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Florida State University and ASU.

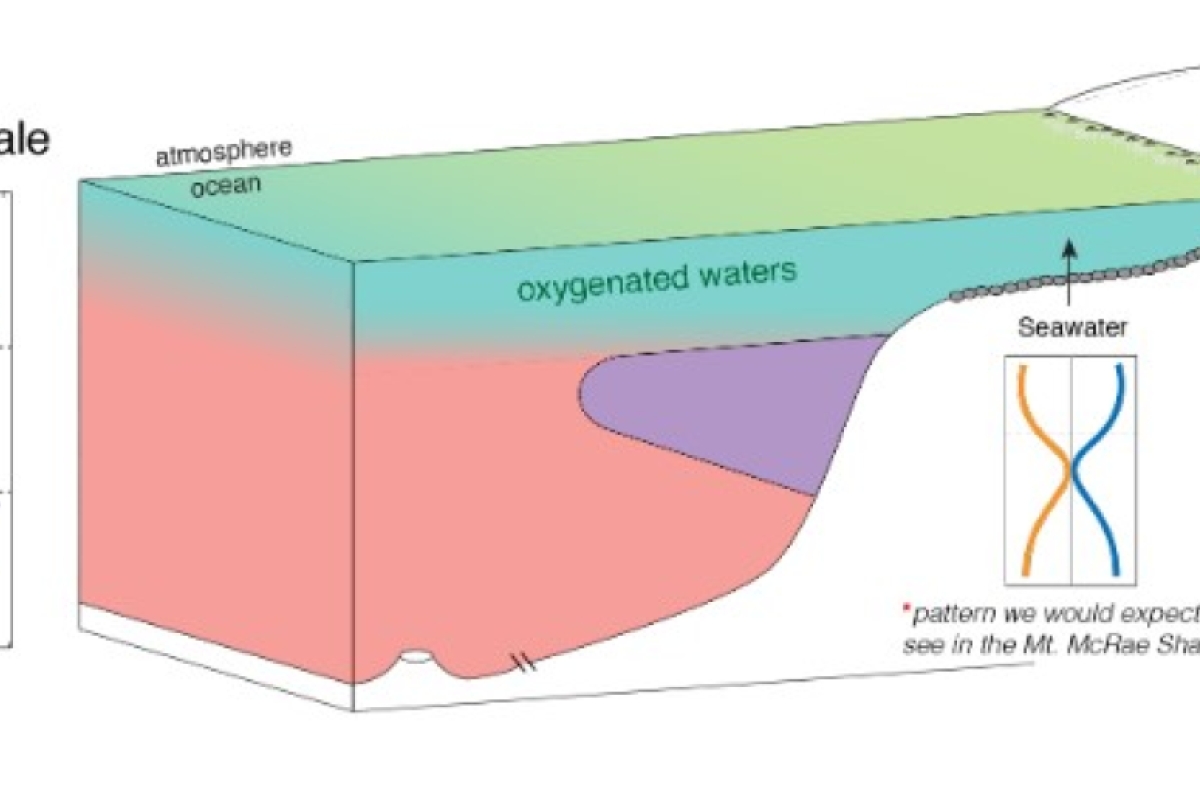

Using mass spectrometers, the team measured the thallium and molybdenum isotope compositions of the Mt. McRae Shale. This was the first time both isotope systems had been measured in the same set of shale samples. As hypothesized, a predictable thallium and molybdenum isotope pattern emerged, indicating that manganese oxide minerals were being buried in the sea floor over large regions of the ancient ocean. For this burial to occur, O2 needed to have been present all the way down to the sea floor 2.5 billion years ago.

These findings improve scientists’ understanding of Earth’s ocean oxygenation history. Accumulation of O2 was probably not restricted to small portions of the surface ocean prior to the GOE. More likely, O2 accumulation extended over large regions of the ocean and extended far into the ocean’s depths. In some of these areas, O2 accumulation seems to have even extended all the way down to the sea floor.

“Our discovery forces us to rethink the initial oxygenation of Earth,” Ostrander said. “Many lines of evidence suggest that O2 started to accumulate in Earth’s atmosphere after about 2.5 billion years ago during the GOE. However, it is now apparent that Earth’s initial oxygenation is a story rooted in the ocean. O2 probably accumulated in Earth’s oceans — to significant levels, according to our data — well before doing so in the atmosphere.”

“Now that we know when and where O2 began to build up, the next question is why,” said ASU President’s Professor and co-author Anbar. “We think that bacteria that produce O2 were thriving in the oceans long before O2 began to build up in the atmosphere. What changed to cause that buildup? That’s what we’re working on next.”

More Science and technology

Breakthrough copper alloy achieves unprecedented high-temperature performance

A team of researchers from Arizona State University, the U.S. Army Research Laboratory, Lehigh University and Louisiana State…

4 ASU researchers named senior members of the National Academy of Inventors

The National Academy of Inventors recently named four Arizona State University researchers as senior members to the prestigious…

Transforming Arizona’s highways for a smoother drive

Imagine you’re driving down a smooth stretch of road. Your tires have firm traction. There are no potholes you need to swerve to…