Editor's note: This story is being highlighted in ASU Now's year in review. Read more top stories from 2018 here.

Dogs — they’re our best friends but there’s still a lot we don’t know about them: what they daydream about, if they’re really smiling, why they’re scared and how we can help. And until Dug the dog’s magical speaking collar from “Up” becomes available on the mass market, we’ll have to use other means to find out.

ASU psychology doctoral candidate Lisa Gunter has spent several years doing just that. A researcher at the university’s Canine Science Collaboratory, Gunter’s work focuses on improving the welfare of shelter dogs. She recently wrapped up three studies on the topic.

The first study found positive effects related to short-term fostering, the second confirmed a relationship between presumed stress behaviors and dogs’ physiological responses, and the third dispelled myths about shelter dog breeds. The latter is currently under review to be published by the open-access scientific journal Plos One.

“I think the aim of sheltering in general is to be doing things that improve the dogs’ well-being or that help them find a home,” Gunter said. “But a lot of times in shelters, we just don’t know a lot about the dogs. And I think if we know more, we can better help them.”

Sleepovers: Not just for kids

The first of Gunter’s recent studies was a larger-scale roll-out of an earlier study in which dogs from a single shelter spent one night away with a volunteer “foster parent.” In the initial study, cortisolCortisol is a hormone involved in the stress response. levels were measured in samples of the dogs’ urine taken at three separate points in time: at the shelter before the sleepover, during the sleepover and back at the shelter after the sleepover.

That study found that one night away from the shelter significantly reduced the dogs’ cortisol levels.

In the larger-scale roll-out, Gunter’s team, which included Erica Feuerbacher of Virginia Tech, received a grant from Maddie’s Fund to expand the study to include dogs from four shelters across the U.S.: the Arizona Humane Society in Phoenix; the Humane Society of Western Montana in Missoula; DeKalb Animal Services in Decatur, Georgia; and the SPCA of Texas in Dallas.

This time around, dogs spent two nights away from the shelter in the home of a volunteer foster parent, and their cortisol levels were measured before they left the shelter, on each day of their time away and for two days after they arrived back at the shelter.

Researchers wanted to look at the two-day post-intervention baseline cortisol level — as opposed to just the one-day post-intervention level — because there was some concern after the initial study that following the intervention, the dogs’ stress may actually increase over the next few days to levels higher than it was before they left the shelter, due to the shock of getting a break and then having to return.

“Some people were like, ‘Well yeah, they get to go spend time in a home but then they have to come back!’” Gunter said.

However, Gunter and her team found that two days post-intervention, the dogs’ cortisol levels were no higher than before they left the shelter for the sleepover. And at all four sites, they found reductions in cortisol levels during the sleepover.

“Our interpretation of [the results] is that these sleepovers are kind of like a weekend to the work week,” Gunter said. “It doesn’t make all the dogs’ stress go away but it lets them go to a house, take a breather, rest and recharge. And then come back to the shelter ready to find their forever home.”

One additional interesting finding was a difference in stress levels of dogs between shelters. What that suggests is that there may be best practices for running shelters that can make them less stressful environments.

Factors such as a lack of social interaction and high noise levels can have a huge effect on dogs’ well-being. According to Gunter, one study even found dogs who had spent six months or more in a shelter showed signs of damage to their hearing.

“The fact that we saw the sleepover intervention working despite the differences in the shelters suggests to us that it would be a useful practice [for shelters to implement],” she said.

Panting and howling? Sure signs of distress

We might think that when a dog pants it needs water or that when it howls it’s just admiring the moon, but we don’t actually have scientific proof of why it’s acting that way. So for another of Gunter’s recent studies, carried out at the Arizona Humane Society and funded by PetSmart Charities, she set out to identify behavioral indicators of welfare by linking them to dogs’ physiological responses.

She and her team analyzed footage of 62 dogs in their kennels over a four-hour period, noting various behaviors throughout. They then compared their findings to physiological data taken from the dogs, including cortisol levels, heart rates and amount of movement, to determine which behaviors were indicative of increased stress.

Behaviors such as barking, howling, pawing at the kennel and panting were shown to be associated with a more engaged stress response.

Though Gunter stressed the results are only preliminary, behaviors such as the dog scratching itself or stretching, which were associated with a less engaged stress response, could be indicative of the dog actually coping with stress.

Taking physiological measurements was key in this study, as it allowed researchers to get a more complete picture of the dogs’ stress response. The better we understand that, the better we’ll be able to intervene and help, through practices like the sleepover intervention.

“If we can find the behaviors that are related to stress or welfare, then we can really start looking at not only how they’re doing in the shelter but what can we do to improve their welfare,” Gunter said.

More than just pit bulls and Chihuahuas

Gunter has two dogs, one of which, Sweetie, is half Chesapeake Bay retriever, a quarter American Staffordshire terrier, an eighth rottweiler and an eighth German shepherd.

“We know that from DNA analysis,” Gunter said. “I never knew what she was for so long, and I totally thought I knew. And I was wrong.”

What she found in the final study was that quite often, so are shelters.

For her master’s degree work, Gunter looked at how labeling a dog as a certain breed can influence people’s perception of its personality and whether or not it gets adopted. For this latest study, she took that a step further.

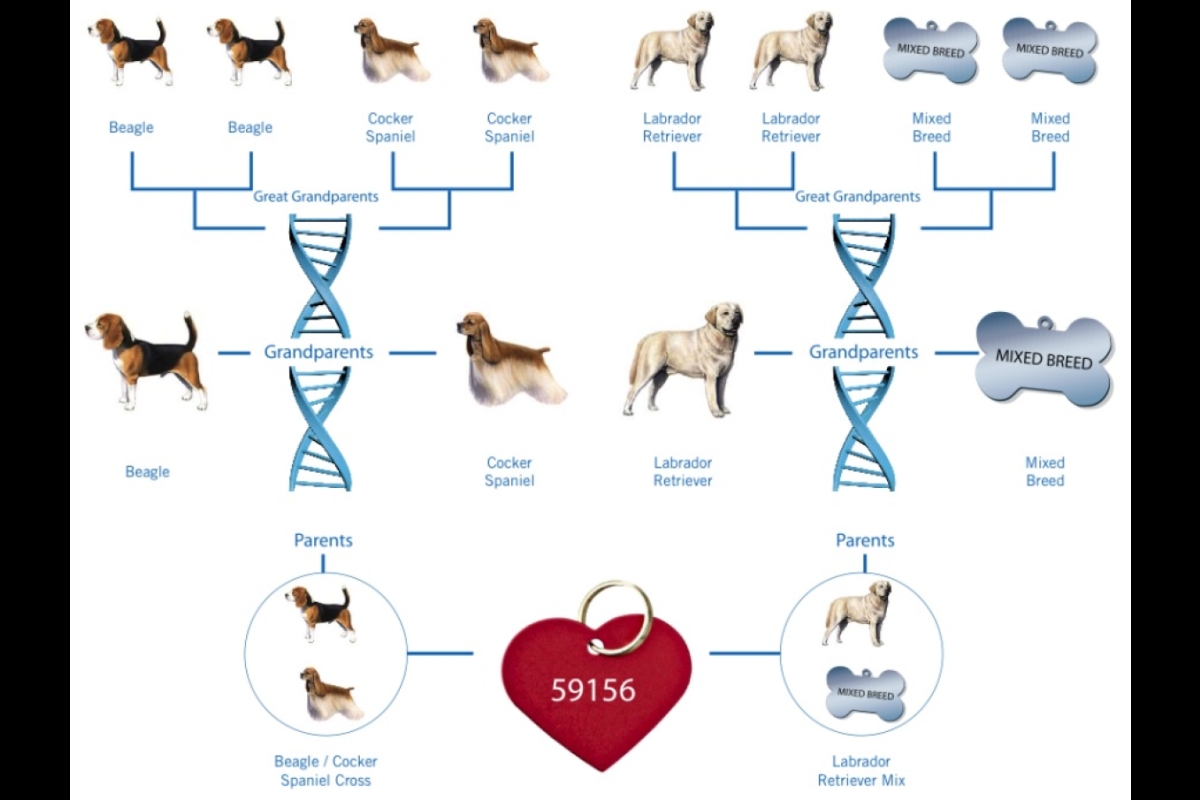

Gunter and her team performed a DNA analysis on nearly 1,000 dogs from two shelters: the Arizona Animal Welfare League and the San Diego Humane Society.

Some key findings:

• Less than five percent of the dogs in the shelters were purebreds.

• Most often dogs had at least three breeds in their heritage, and sometimes as many as five.

• Over 125 breeds were identified across the nearly 1,000 dogs. More than 90 of those breeds were shared between dogs at the San Diego and Arizona locations.

“So we’re kind of selling dogs short when we’re thinking they’re all Lab mixes and border collie mixes or pit mixes or Chihuahuas,” Gunter said. “Shelter dogs are way more interesting than that. There’s a lot of variability in breed and in combinations.”

One dog she and her team came across, Bruce, turned out to be a beagle, cocker spaniel and Labrador mix.

“Previous research that’s been done suggests that one reason why folks don’t go to the shelter is because they don’t perceive that the type of dog they’re looking for is there. And I think what that says is, well, maybe (they are) though,” Gunter said.

Researchers addressed what Gunter calls “a common refrain on the West Coast,” that shelters only have pit bulls and Chihuahuas. What they found was that "pit bull-type“Pit bull-type” breeds include American Staffordshire terriers, Staffordshire bull terriers, American bulldogs, bull terriers, etc., each of which is its own separate breed." breeds and Chihuahuas only accounted for about 50 percent of dogs in the shelters.

They also looked at how accurate shelter staff were at identifying dog breeds, based on the dogs’ DNA analyses. When it came to picking out one breed in the dog’s overall makeup, the staff were right about two-thirds of the time. When staff was asked to pick out more than one breed (which most dogs in shelters are), they were right only about 10 percent of the time.

“That that has nothing to do with the expertise of staff,” Gunter said. “I think that has everything to do with [the fact that] it’s a really hard job to just look at a dog and know what it is.”

She added that we don’t really know how multiple breeds in an individual dog influence its behavior anyway.

“Just because a dog is a border collie-Lab mix doesn’t mean it’s going to herd and swim well,” she said. “At the end of the day, it just matters if they’re a good fit for your home and for your life and for your family. And that’s something that you’ve just got to take on a dog-by-dog basis.”

Top photo: ASU psychology doctoral candidate Lisa Gunter play with Cera, a mixed breed, at the Arizona Humane Society Sunnyslope campus in Phoenix. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

More Arts, humanities and education

Local traffic boxes get a colorful makeover

A team of Arizona State University students recently helped transform bland, beige traffic boxes in Chandler into colorful works of public art. “It’s amazing,” said ASU student Sarai…

2 ASU professors, alumnus named 2025 Guggenheim Fellows

Two Arizona State University professors and a university alumnus have been named 2025 Guggenheim Fellows.Regents Professor Sir Jonathan Bate, English Professor of Practice Larissa Fasthorse and…

No argument: ASU-led project improves high school students' writing skills

Students in the freshman English class at Phoenix Trevor G. Browne High School often pop the question to teacher Rocio Rivas.No, not that one.This one:“How is this going to help me?”When Rivas…