Working through school violence in youth literature

Visiting author Tom Leveen, ASU Professor James Blasingame address the value of representing real-life trauma in YA fiction

“Gunfire Erupts at a School. Leaders Offer Prayers. Children Are Buried. Repeat.”

The title of Dan Barry’s Feb. 15 New York Times column following the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, may seem callous, but its message rings true: Perhaps the most shocking thing about school shootings in America is that they are no longer shocking.

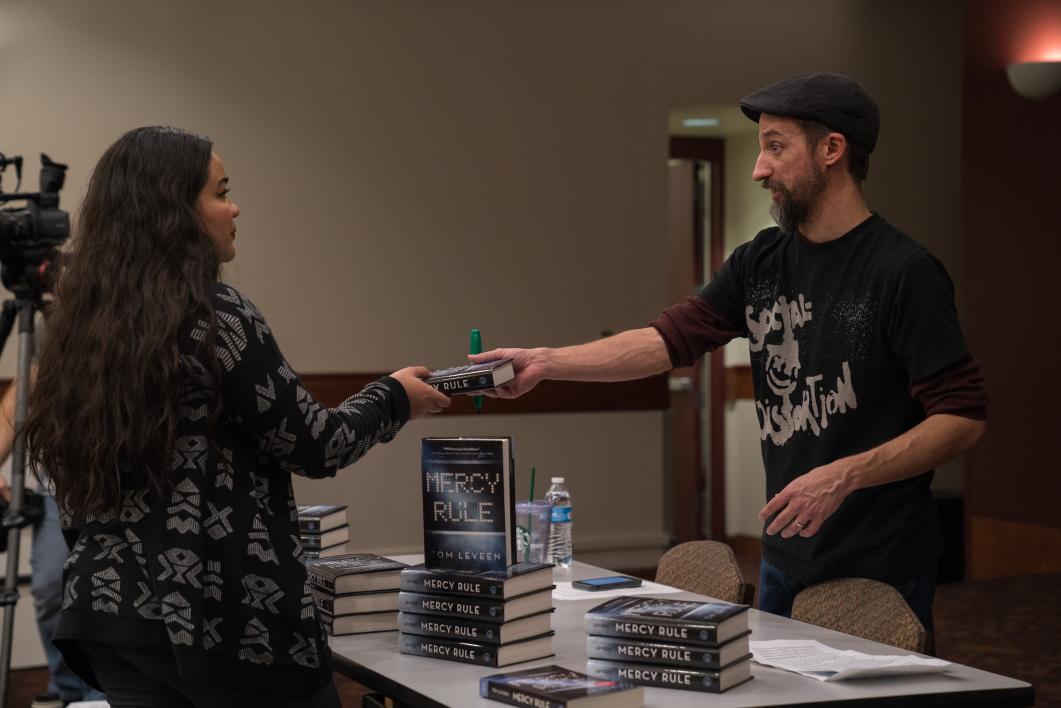

“We grew up post-Columbine. This is normal for us. We’ve never had a time where we didn’t have lockdown drills,” Kyra Sciabica said. The psychology and English undergrad shared her thoughts on the subject at a recent event at Arizona State University's Memorial Union, where local young adult author Tom Leveen appeared to promote the release of his latest young adult fiction novel, “Mercy Rule,” which culminates in a school shooting.

Leveen, who graduated from high school in 1992, remembers a time before Columbine. The timing of his latest book release and the nightmare that unfolded in Parkland just a week earlier were purely coincidental — he began writing “Mercy Rule” three or four years ago — but he can’t say he was surprised.

“When [Columbine] happened, it was a tragedy,” he said Feb. 21. “It rocked our world, but it was an isolated thing. And now it’s not.” The Parkland shooting “was just statistically likely at this point. And that’s the hell of it. That’s the maddening thing.”

Before Leveen spoke last week, Sciabica and other students in Professor James Blasingame’s English 471: Literature for Young Adults course gathered in small groups to discuss their assigned reading, “It’s Kind of a Funny Story,” a 2006 novel by Ned Vizzini in which the 16-year-old main character is hospitalized for depression.

It’s one of hundreds of examples of young adult literature that deals with real-world issues faced by teens every day, Blasingame said. Another is the book “Speak,” by Laurie Halse Anderson, which deals with rape.

It wasn’t until after Columbine, though, that we really saw a rise in books involving school shootings. Since then, we’ve seen “Give a Boy a Gun” by Todd Strasser, “Whale Talk” by Chris Crutcher and “Nineteen Minutes” by Jodi Picoult, just to name a few.

And if you ask Blasingame, “a well-written young adult novel can save a life.” He has interviewed scores of authors who have told him time and again how often they receive letters and emails from students who tell them their book changed their life for the better because it validated their personal experience and made them feel less alone.

Still, some approach with caution the proliferation of books that depict violence as commonplace.

“While reading about a character successfully coping with such an event could promote well-being, particularly if this is accompanied with a conversation with a caring adult, there is also concern that it may unnecessarily create fear,” said Sarah Lindstrom Johnson, an assistant professor in ASU’s T. Denny Sanford School of Social and Family Dynamics.

Some research seems to suggest that the value of books like “Mercy Rule” is their ability to teach kids about warning signs, what could lead to violence in schools and how to prevent it.

In a 2009 study out of Iowa State University, researcher Jill Hathaway found that when students read books about teen violence, particularly school shootings, they had a higher level of cognizance of what caused the violent behavior.

According to Blasingame, bullying is a big cause, but so are unhealthy relationships, whether romantic, platonic or familial. That all hearkens back to what Leveen had in mind when he was writing “Mercy Rule.”

A lot of the things that happen in the book are stories he heard from real students at schools he has visited. The thread that seemed to tie all their experiences together was the theme of dismissal, whether they were dismissed by peers in the form of bullying or by friends and family who didn’t take the time to sit and really listen to their problems and concerns.

“I used those stories because I wanted to draw characters that we could all relate to and that would surprise us, and make us think differently and realize that we need to listen and have conversations,” Leveen said.

“That’s what’s missing, I think, not only [in our everyday lives] but also on a larger scale. … We’re venturing into another discussion about gun control, and that’s great. But do we know how to talk about this? Or have we completely abandoned any sense of procedure, any sense of meeting someone in the middle and actually working on some kind of solution, or are we just completely blocking each other out?

“So I hope this book will make people be more considerate about how they engage with people in the future.”

More Arts, humanities and education

Small presses dealt big blow

A mighty rumble reverberated throughout the publishing industry late last month with the abrupt closure of a well-known book distributor. Small Press Distribution, which has distributed books for…

'Living dress' wins Eco-Chic sustainable fashion contest

When Elena Marshall is done showing off her award-winning “living dress,” she’ll bury it in her backyard. The dress, a chic design with a strapless bodice and flouncy skirt, is made of recycled…

ASU Symphony Orchestra welcomes visionary conductor Jonathan Taylor Rush

Guest conductor Jonathan Taylor Rush will join Arizona State University’s Jason Caslor, director of bands, to lead the ASU Symphony Orchestra in their final concert of the season, “Trailblazers,” on…