ASU psychologists at the Children’s Museum of Phoenix exhibit how children think

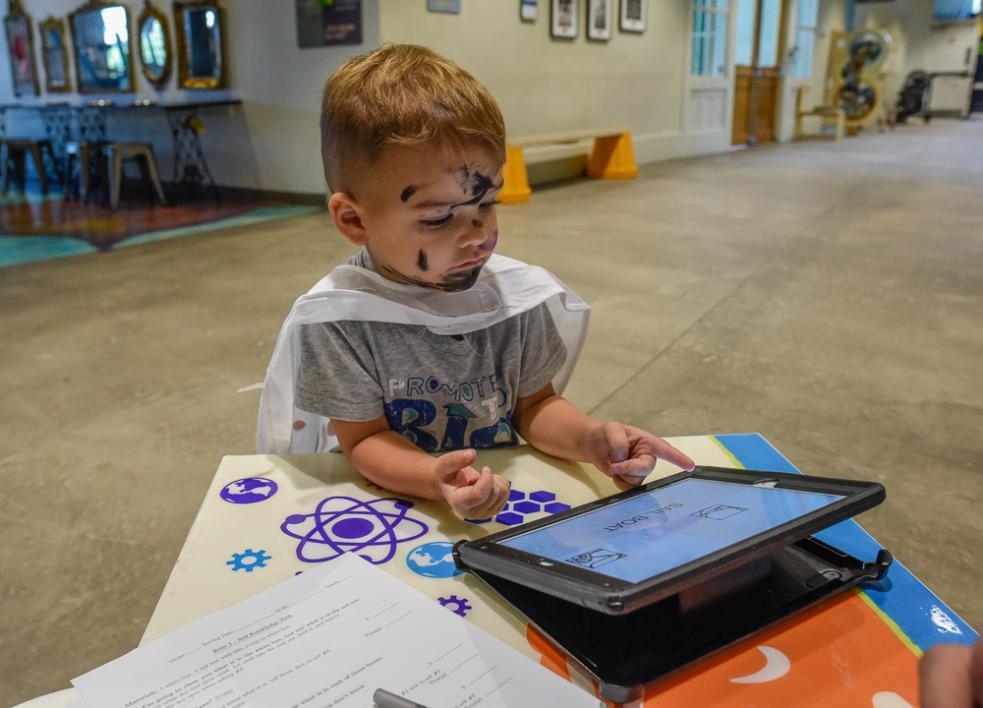

Quenten Benner, undergraduate student researcher in the Department of Psychology, explains the theory of a mind research experiment to a child at the Children's Museum of Phoenix. Photo by Jack Guckian

On the first floor of the Children’s Museum of Phoenix, an Arizona State University scientist from the Department of Psychology sits across a table from a 2-year-old child. The child’s father stands nearby. There are four boxes on the table: red, blue, green and white. One at a time, the boxes open and the child looks at what is inside. The green, white and blue boxes are empty, and the red box holds a ball. All the boxes close, and the psychologist asks the child where the ball is. The children’s answers often surprise both researchers and parents.

William Fabricius, associate professor of psychology, and his lab study how children think about what they know and what other people know.

“It is really interesting every time to see the parents’ reactions to what their kids know and don’t know,” said Quenten Benner, a junior who conducts research in the Fabricius lab as a student volunteer.

“No one has tested children of this age in these simple search tasks. We just assumed they knew,” Fabricius said. “We think they are imitating adults hiding the object, and that may be how they learn which visual cues to use in a search.”

This study sheds light on how children learn. It also suggests when the brain’s motion and visual systems start to work together. Fabricius said the study findings could be useful for robotics and artificial intelligence limb biomechanics.

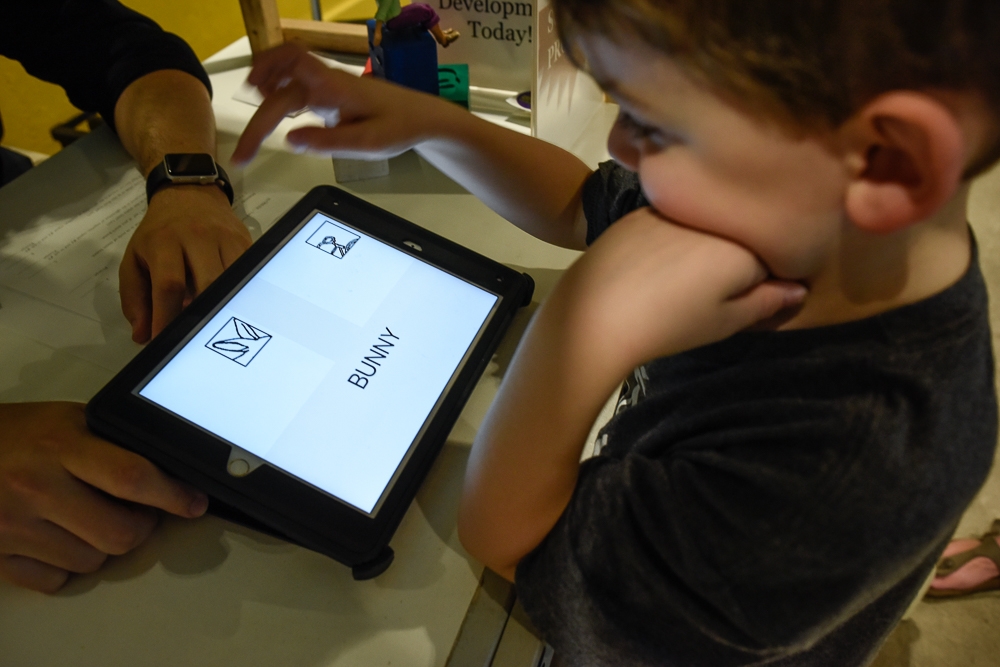

Gonzales also ran a different version of the box experiment to test what children know about the thoughts of others. The psychologist held a doll that looked into each box at the same time as the child. After the boxes closed, the psychologist asked the child where the doll thinks the ball is. Gonzales discovered when children are about 3 1/2 to 4 years old, they can answer correctly for themselves but not for the doll.

“For a long time, developmental psychologists thought that kids understood what they know at the same time as they understood what others know,” Gonzales said. “We showed that kids learn about themselves first, before they understand what others think.”

Gonzales, Fabricius and Anne Kupfer, who directs the Child Study Lab in the psychology department, recently published this finding in Child Development.

Partnership between research and education

Experiments with young children can be difficult to do on a college campus. Developmental psychology research groups like the Fabricius lab often conduct experiments off campus, out in the community. Christopher Gonzales, a graduate student in the psychology department, suggested to Fabricius that running experiments at the museum would be an easy way to reach study participants.

“He had to convince me that this would be a great place to test kids,” Fabricius said. “Two years and over 1,000 kids later, I have to admit he was absolutely right.”

When Gonzales first contacted the museum, he said he was met with open arms. He started running experiments on folding tables with an ASU psychology department banner. The museum has since adopted the educational model of the National Living Laboratory, an organization that works to increase public access to science by placing researchers in local museums. Funds from the Living Laboratory have provided a moveable exhibit that encourages interaction between ASU scientists and museum visitors.

“We engage with families and ask them if they want to help a scientist and learn about children with hands-on activities,” Gonzales said. “We can show them a demo, or they can participate in the scientific process.”

The presence of ASU psychologists in the museum benefits both scientists and the public. The scientists have participants that represent the community. The public learns firsthand what ASU researchers are studying. Fabricius and Gonzales said that over 1,000 families have chosen to participate in experiments so far, and they have explained their research to at least twice as many families.

Experiments at the museum also benefit scientists worldwide because the lab archives data with Databrary, a video library for research on development. When parents choose to participate in an experiment, they can also agree to allow the video recordings to be used by other scientists.

To date, the Fabricius lab experiments at the museum have contributed data for two undergraduate honor’s theses. Museum experiments have also provided undergraduate research opportunities to almost two dozen students, like Benner, with the Fabricius lab.

“We have had about 12 to 24 undergrads working with us, spending 10 to 15 hours a week to help at the museum,” Gonzales said. “We go in and test on the weekends, and during the summer, we tested every day.”

The groundwork Gonzales laid at the museum will continue to link ASU scientists with the public for the foreseeable future, said Melanie Martin, early childhood specialist with the Children’s Museum of Phoenix.