Arizona State University archaeology student Claudine Gravel-Miguel went into her field of study 10 years ago simply for love of travel. Now, after falling in love with the science as well, her research has taken her to the Caverna delle Arene Candide in Italy, where she made a surprising discovery that is changing the way scientists look at human culture in the Paleolithic.

Gravel-Miguel, a doctoral student in the School of Human Evolution and Social Change, freely admits that she initially chose to study archaeology because she wanted a job that would let her see new places. But after her first class, it was questions about people — past and present — that soon captured her interest.

Her research focuses on using new tools like computational modeling to see how climate change and geography impacted prehistoric human mobility and social networks. Although that's not as effused with Hollywood glam, Gravel-Miguel argues that this is the reality of 21st-century archaeology.

“It may be cliché, but I think there is still a misconception that archaeologists do all their work in the field,” she said. “One of the first things I tell people when I talk about my work is that most of us spend more time in the lab and on computers than out on the terrain.”

This ability to bring new perspectives to old archaeological puzzles is exactly what led Gravel-Miguel to a recent, groundbreaking discovery in the Caverna delle Arene Candide.

ASU archaeology student Claudine Gravel-Miguel documents pebbles on a beach near the site. Photo by Genevieve Pothier Bouchard

This site, a cave high up a limestone cliff, was made famous in the 1940s when researchers found the remains of around 20 hunter-gatherers who were buried there 13,000–11,000 years ago. Throughout decades of excavation, archaeologists have found (and mostly ignored) pieces of small oblong-shaped stones. But Gravel-Miguel and the site director, Julien Riel-Salvatore, noticed that the stones were out of place in the cave — they had smooth surfaces like river rocks and all shared the same long, flat shape.

When she expressed interest in these peculiar stones, Riel-Salvatore encouraged her to investigate them further.

“The pebble project actually almost fell in my lap,” she said. “To be honest, I thought it would be a very simple study.”

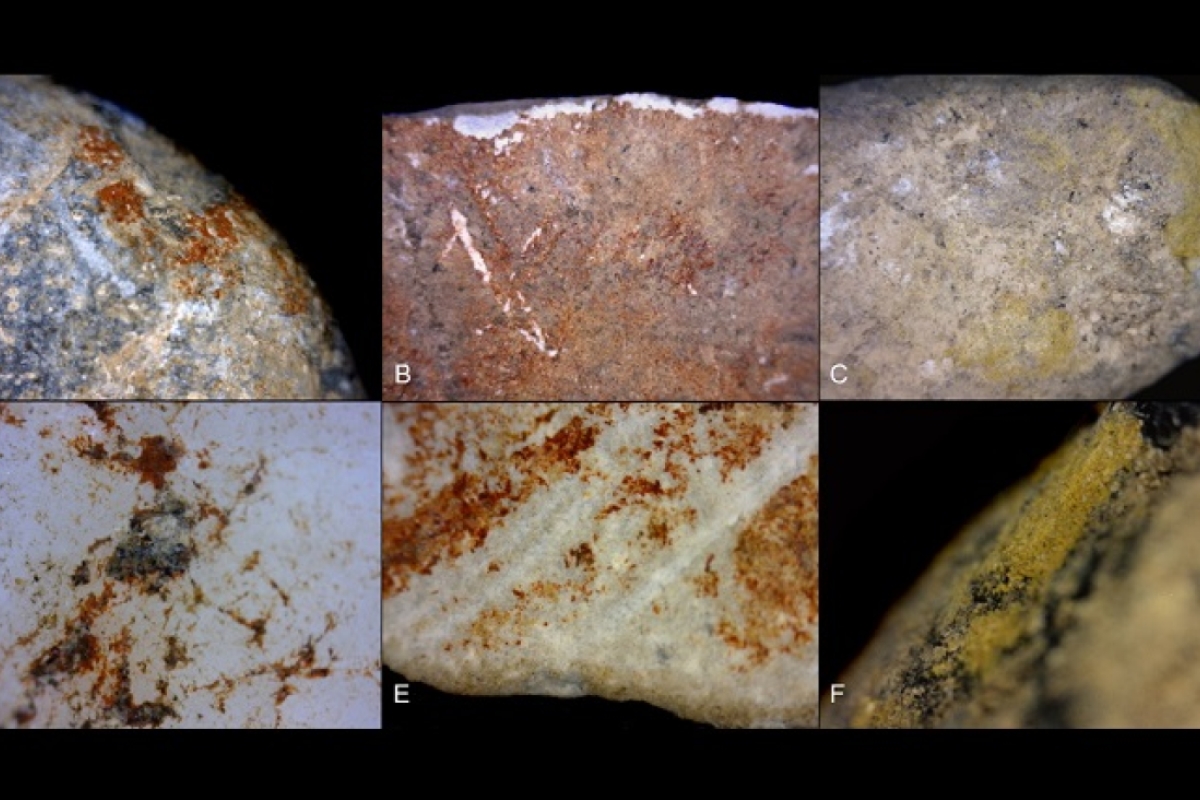

Gravel-Miguel and her team quickly deduced that the hunter-gatherers had looked for and specifically chosen these stones from nearby beaches. However, microscopic analysis also revealed that the stones held traces of ochre, a red pigment frequently used by prehistoric people to paint the bodies of the deceased.

So why were the majority of these stone application tools carefully selected, only to wind up broken in a cave some distance away? In her recently published paper, Gravel-Miguel proposes that people smashed them intentionally after use.

“One would have had to handle the pebble by wrapping the hand around it, which should have prevented a break along the short axis,” she said. “Therefore, the shape and use wear of the piece tell us that the pebbles were not likely broken by accident while they were being used.”

The intention behind the breaks suggests it was likely part of a ritual act that symbolically killed the stones’ power over the dead. Such practice has been documented in the Neolithic, but never before in the Paleolithic, making this case the oldest example ever recorded.

Additionally, Gravel-Miguel found that each broken stone the team excavated had pieces missing from its fragments. She found only two refitting parts, but these gave her a clue about the fate of the other absent pieces.

“The two pieces of one refitted pebble have very different patinas,” she explained. “One is red and the other white. This shows that the two pieces were not discarded in the same place after the break, which suggests that the break may have had some meaning and that some of the pieces may have been curated.”

In her paper, Gravel-Miguel uses this data to support a hypothesis that one piece of each stone was left at the cave, while another was taken by a loved one as a way to remember and connect with the dead.

“This research reveals a new dimension of the burial rituals that took place this far back in time and strengthens our assumption that death has always been a very important component in the life of the living,” she said.

One of the next steps for this project is to expand research into other nearby archaeological sites from the same time period. This will help the team figure out if the practice of stone-smashing and fragment-keeping is something that was done locally by one group, or something that was part of a broader culture shared throughout the region.

Gravel-Miguel has also been left curious about whether the ritually broken stones were deposited as grave goods — that is, intentionally placed in the burial — or if they were just tossed away after the ritual. To find out, she will need to go back to the artifact collection of the archaeologist who excavated the site in the 1940s.

“There’s a lot more work to be done on this topic. It’s exciting,” she said.

Top photo: Public-domain photo of cliffs on the coast of Liguria, Italy.

More Arts, humanities and education

Local traffic boxes get a colorful makeover

A team of Arizona State University students recently helped transform bland, beige traffic boxes in Chandler into colorful works of public art. “It’s amazing,” said ASU student Sarai…

2 ASU professors, alumnus named 2025 Guggenheim Fellows

Two Arizona State University professors and a university alumnus have been named 2025 Guggenheim Fellows.Regents Professor Sir Jonathan Bate, English Professor of Practice Larissa Fasthorse and…

No argument: ASU-led project improves high school students' writing skills

Students in the freshman English class at Phoenix Trevor G. Browne High School often pop the question to teacher Rocio Rivas.No, not that one.This one:“How is this going to help me?”When Rivas…