Professor uncovers lost stories of Cesar Chavez, United Farm Workers movement

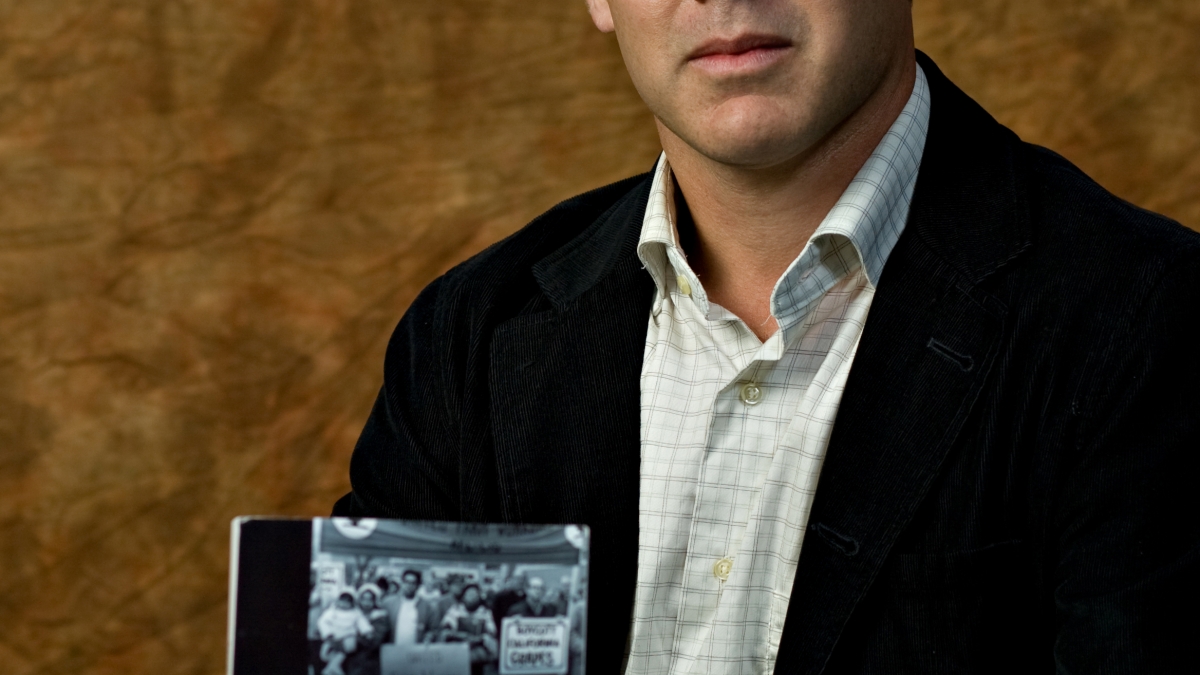

Cesar Chavez – the man, the myth and the legend – helped bring the plight of farm workers into the international spotlight at a time when all hope seemed lost. But Matt Garcia, the director of ASU’s School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies, says the story of Chavez and the farm worker movement is not so simple.

In his new book, titled “From the Jaws of Victory: The Triumph and Tragedy of Cesar Chavez and the Farm Worker Movement” (University of California Press), Garcia brings to light the individuals who helped Chavez in making the organization succeed and also uncovers some of Chavez’s secrets, which he believes directly contributed United Farm Workers (UFW) decline.

In 1962 Chavez, Gilbert Padilla, Dolores Huerta and many others worked together to create the UFW to raise awareness about the deplorable conditions and wages for hard-working farm laborers. They successfully organized many boycotts, including the infamous grape boycott, which hit growers and suppliers extremely hard. In fact, it was this strategy that made Chavez a household name. But Chavez didn’t do this work alone.

To bring the boycott from the rural fields to the urban cities, hundreds of college students took time away from their studies to fight for the farm workers they would never meet. In fact, Garcia says he found that young people of all races worked together to put pressure on the grape growers, consumers and politicians, resulting in the creation of official labor contracts in 1970. Garcia says his research dispels the popular perception that the movement was carried out primarily by Mexicans, and to a lesser extent, Filipinos.

“The story of the boycott demonstrates that youth of all backgrounds can work together to change the world. It shows that when young people decide that there is something worth achieving, they can do it,” Garcia says. “While the UFW ultimately didn’t achieve its goal of becoming an effective voice for all farm workers in this country, for a time it did. It was amazing – in five years, it went from no movement to the first contracts for farm workers in the state of California.”

The most shocking discovery he unearthed in his research was Chavez’s intent to turn the UFW into an “intentional community.” Following the path of Chuck Dederich, who started The Synanon, Chavez fixated on building a community “that revolved around his Chavez’s beliefs and values.” According to Garcia, in an attempt to accomplish this task, Chavez moved the UFW headquarters to La Paz, Calif., and began asserting his will over other leaders in the organization. Garcia’s findings reveal that Chavez was suspicious of anyone who shared opposing political views and purged members who questioned him.

So what prevented Chavez from turning the UFW into a cult-like organization? Garcia says that some members of the executive board fought against changes on the inside, while former members whom Chavez purged from the UFW began to communicate their opposition from outside the organization.

“The existence of former boycott volunteers was critical to the formation of checks against Chavez’s power,” Garcia says. “In interviews, members of the inner circle told me that the boycott was critical in preventing UFW from going the way of other intentional communities of the 1970s.”

While Garcia uncovered many unknown facts about the UFW, his favorite discoveries were of the inspiring people who helped Chavez advance the movement – people like Elaine Elinson, who singlehandedly extended the grape boycott to England, and Jessica Govea, a farm worker’s daughter who extended the grape boycott to Canada – all because they believed in the cause.

Gilbert Padilla, Chavez’s right-hand man, also played a large role in the creation and success of the movement, yet remains largely unknown. Recruited by Chavez, Padilla was vital in developing and implementing many strategies that caused the movement to progress and succeed.

“He deserves as much recognition as Chavez for starting the movement,” Garcia says. “In fact, when he stood up at the first meeting among Mexican and Filipino farm workers in Delano, people mistook him for Chavez because he is such a charismatic person.”

It is Garcia’s hope that his book will not only paint a more accurate picture of Chavez, but also reveal the stories of complexity and heroism of the many men and women who helped create the union.