In memory: senior research scientist Russell LoBrutto

Russell LoBrutto, a senior research scientist at ASU’s School of Life Sciences, in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, died peacefully, March 25, surrounded by his family. A memorial service will take place at 4 p.m., April 15, at the Valley Unitarian Universalist Congregation, 6400 West Del Rio Street, in Chandler.

LoBrutto was born in 1952 to Frank and Louise LoBrutto. The second of five children, he grew up in his parent’s home in Buffalo, New York. He received his bachelor's degree at Cornell University and his doctorate in biophysics at the State University of New York (SUNY) at Buffalo. This was followed by postdoctoral studies at SUNY at Albany, and then at the University of Pennsylvania in the Johnson Foundation prior to becoming an assistant professor of physics at Northeastern University in Boston.

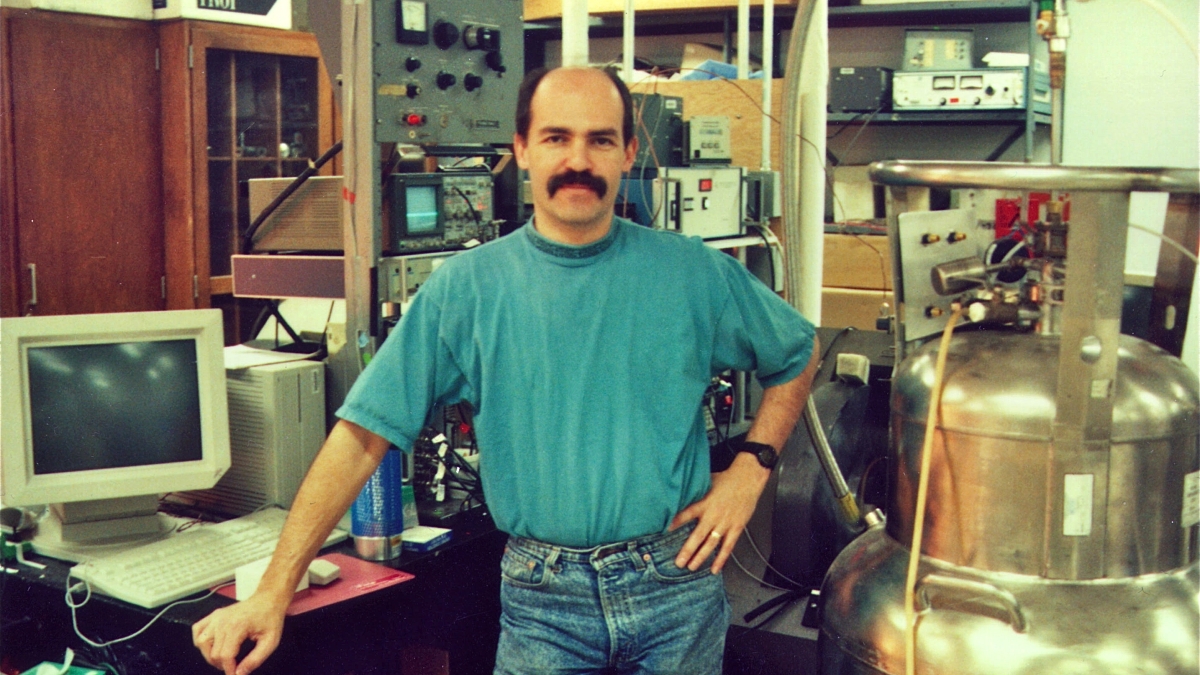

In 1991 he moved to Arizona with his wife Kellie Walker to manage the new Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) Spectroscopy Facility in the ASU Plant Biology Department. A National Science Foundation (NSF) grant awarded to faculty in the ASU Center for the Study of Early Events in photosynthesis provided the first EPR spectrometer, which is an essential tool in studying photosynthesis. At the time, the only other plant biology department in the nation to have an EPR facility was UC-Berkeley.

“We were so lucky to have Russ take charge of the EPR facility because of his extensive experience in this complex technology,” Frasch said about his colleague. Frasch and LoBrutto worked extensively together on several projects. “Russ was very easy-going and a sincere scientist. He loved to discuss ideas and interpret data and took great joy in the whole process of discovery.”

LoBrutto, an expert in the area of a sophisticated EPR technique known as electron spin-echo envelope modulation (ESEEM) spectroscopy, had built his own pulsed EPR instrument from the ground up. By bringing his ESEEM spectrometer to ASU, he greatly expanded the capabilities of the facility. A few years later, he obtained NSF funding allowing him to expand the EPR facility further to include, among other things, electron-nuclear double resonance spectroscopy (ENDOR).

“Russ embodied what transdisciplinary means,” Frasch said. “He worked on many projects while he was here, some of them not in photosynthesis. He had strong collaborations with the faculty at the University of Wisconsin’s Enzyme Institute, and across the country he was highly respected in his knowledge of EPR spectroscopy.”

George Reed, a professor of biochemistry at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, met LoBrutto 30 years ago. The two became close friends when they collaborated at the University of Pennsylvania during the time that LoBrutto built the pulsed EPR spectrometer.

“Russ was an ‘Angus MacGyver’ in putting together sophisticated spectroscopic instrumentation,” Reed said. “I remember the excitement we shared in telephone conversations about the experimental results we obtained. Russ was kind, considerate, loyal and had a terrific sense of humor,” he added.

LoBrutto taught a course for graduate students on how to use EPR spectroscopy, which for many scientists, is an intimidating and complex technology. Working with scientists in a variety of fields, he also taught others about the potential benefits of using EPR technology in chemistry, biochemistry and engineering.

While colleagues describe him as a brilliant scientist, they also said he was a strong family man. Married for nearly 24 years, the couple met through a mutual friend at a house-painting party.

“Russ was very interested in the world of ideas. He was well-read and enjoyed talking about ideas, literature and theatre. He was a very good conversationalist,” said his wife, Kellie. “As a scientist, he didn’t get discouraged. If things didn’t work out, he would try a new way. And as a father, he was unfailingly kind, positive and protective. He always said, even with cancer and the Parkinson’s, he felt lucky because he had a career he loved, was able to contribute to science, and take care of his family.”

LoBrutto leaves behind his wife and their three children Ben, 21; Bryan, 19; and Jolie, 14.

Several years ago, Parkinson’s disease forced LoBrutto to retire early from his research. However, he kept up his love of astronomy. He purchased a high-powered telescope to take in the night skies and frequently hosted viewing parties at his home with friends and family. Late in 2010, he was diagnosed with cancer and succumbed following a valiant fight. Donations may be made in his memory to help further Parkinson’s disease research.