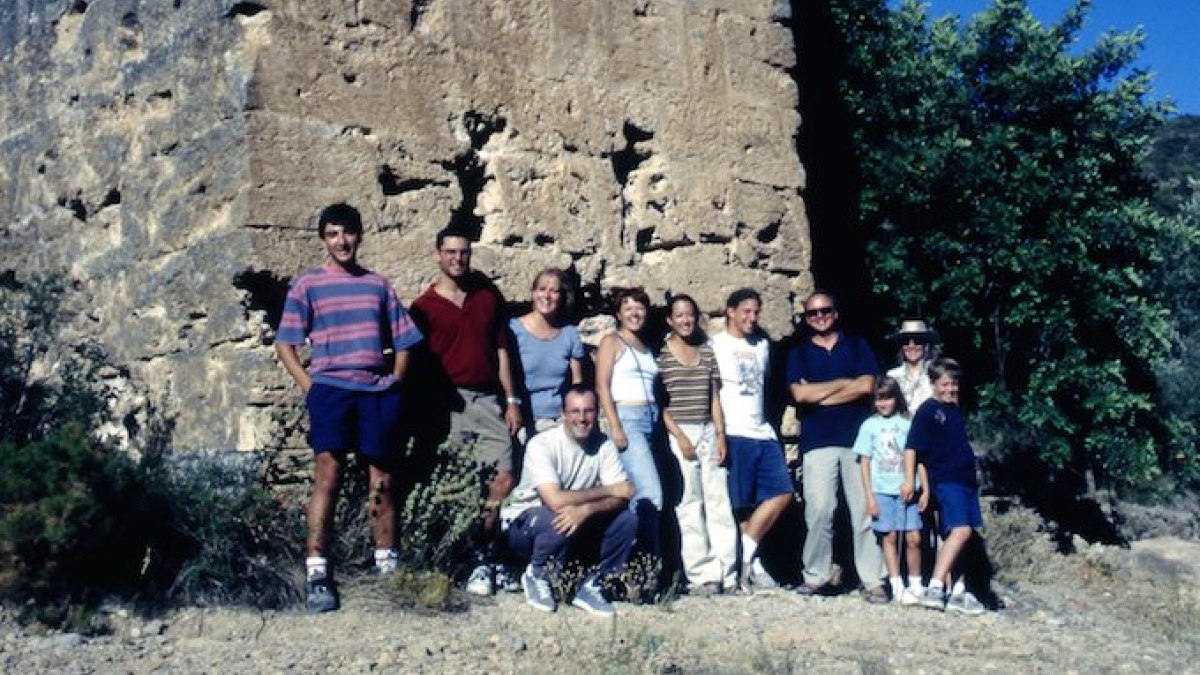

Innocents abroad: ASU fieldwork with family

Editor's Note: Growing up, ASU student Erin Barton and her brother often accompanied their archaeologist parents on research excursions. Here, Barton shares stories about bringing families into the field – and the challenges and rewards that come with it.

It was always hot. It was always dry. We were always covered in dust.

I stole rolls of neon-colored field tape to tie things up with; my brother preferred the duct tape. I tried to make spears out of Spanish Daggers. My brother carved bows and arrows. We both tried to make stone knives like the crewmembers did and, when that failed, we tried to find out exactly how sharp a trowel could be.

I sat on many piles of dirt and asked, “Is this is a shard? Is this a shard?” Once, I sat on a cactus that had been hidden under a pile of dirt.

My archaeologist parents and their intrepid crew rarely left us behind when they went on excursions. My mother says this led to many “comical situations, which involved the children, [and are still] recounted in social settings.” It also led to my brother and me collecting a number of equally comical tales about the various exploits of Our Parents and the Crew. We also still recount them.

On one occasion, the Tonto National Forest caught on fire while we were in it. This did not stop the fearless team of archaeologists. Our parents and the crew kept right on excavating. They just got firefighter radios so they could keep abreast of the fire’s progress, and passes to get them through barricades.

On another occasion, the old masia where we stayed in the Valencian countryside of Spain became infested with ticks. I had to stop playing with the three dogs that lived there because they were infested. Fortunately, the Spanish members of our crew all carried lighters, as the best way to kill the parasites was to set them aflame. At every gathering it became a common sight to see one of the crew lean down to roast an arachnid. I took great joy in yelling, “tick!” and pointing out the next to be executed.

'Faculty brats'

These were just some of the experiences I had as the child of two ASU affiliated researchers. My father, Michael Barton, is a professor in the School of Human Evolution and Social Change. My mother, Margaret MacMinn-Barton, worked as a research affiliate and co-investigator on several of his research grants. My brother and I were what’s known in less proper parlance as "faculty brats" – children who grow up within the cloisters of academia, or for a lucky few, being carted about the globe on various fieldwork projects.

Rachel McKenny describes the experience eloquently in her article, “Faculty Bratitude,” in the Chronicle of Higher Education: “Being a ‘faculty brat’ meant joining in on adult conversations early. It meant cookouts on warm summer evenings with the jargon of politics flowing as fast as the beer. It meant that the faculty became a familiar cast of characters throughout my childhood.”

Although growing up in an academic family has unique aspects, they’re not uniform. Not all faculty travel for research, for instance, and some may choose not to bring their family.

Jim Elser, a limnologist in ASU’s School of Life Sciences, a unit within the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, is one researcher who, like my parents, brought his children to a number of research sites starting when they were very young. One place they visited frequently was an experimental lake research facility in central Ontario, Canada.

“That was kind of a cool place because the field station was in the middle of nowhere and they’d give you sort of a rustic little cabin to live in,” Elser says. “So the kids sort of had the run of the place. They would have a good time, and we’d take them out sampling in the boats ... that was always an adventure for them.”

Elser also took his family to field sites in Norway, Japan, Colorado and Mexico. Sometimes his sons helped with the fieldwork; Tim Elser helped far more than my brother and I ever did.

“I translated for him [Jim Elser] on a research trip to Cuatro Cienegas, Mexico,” writes Tim in an email. “My summer job after leaving high school was collecting water samples for one of his projects in the Rocky Mountains.”

However, Tim says that despite the good experiences he had on his father’s trips, the biggest impact they had was to show him what he did not want to be when he grew up.

“The most direct impact on my professional development didn't really come from going along into the field,” he writes. “It was the pre-teen/teen summers spent bored out of my mind in his lab that turned me off of natural sciences.”

Tim is now nurturing a love for applied math as a data scientist in San Francisco.

Adventure – and 'bored out of our minds'

Being bored in the lab may be a common thread among children of faculty. As a child, I often skulked about the halls of what is now ASU's School of Human Evolution and Social Change and frequented my father’s basement office. (We joked that, as an archaeologist, he had to live underground.)

The place smelled like dug-up earth and dust. There, I hid from graduate students, and played with the plastic dinosaur skeletons my father kept for me. When not re-enacting battles, they sat next to countless dissertations, bone-dry academic texts and histories with very long titles. I thought their molded death grins made the whole place more cheerful.

Although we often visited dig sites, my brother and I were still frequently “bored out of our minds” there, as well. Not being archaeologists, we could only spend so long walking about and staring at rocks before being overtaken by a great ennui, causing us to lie down despairingly in the dust.

Whenever anyone asked (and everyone always asked) whether we wanted to be archaeologists when we grew up, the answer was always delivered bullet-fast. “No!”

But I share another experience with Tim, which is the memory of many halcyon summer days spent running wild.

“Going out to research stations as a child was pretty idyllic – fishing, swimming, frogs to catch, berries to eat and lots of dogs to play with,” he writes. Experiences like these made all the boredom worth it.

Like Tim and many other children of researchers, I had no desire to follow in my parents’ footsteps; however, there were many things about their research that fascinated and inspired me. Perhaps it is not surprising then that I did end up working in a research lab for a time as a college student. I even dug a few holes (ecological, though, not archaeological).

Frequent international travel, plus hosting a constant rotation of professors and graduate students from all over the world, taught me how to adapt to new situations and cultures. I also tend to pay attention to what's going on in multiple parts of the world because I have many places that I care about, with friends and acquaintances spread all across the globe. I am a “citizen of the world."

Family-friendly

According to my mother, the anthropology department never gave her or my father any trouble over the fact that they took us with them into the field. Their experiences defy the common narrative that academia is unwelcoming to researchers with families.

The idea that it is difficult to balance an academic lifestyle (particularly one involving fieldwork) with a family is one that crops up often in higher education media. Being a parent is widely viewed as an inconvenience, or even a career killer, particularly for women.

The situation, however, seems to vary at different universities, and even between schools within a university. Although balancing work and family presents difficulties for parents in any field, the researchers I interviewed did not feel unduly burdened by their unique circumstances.

Abigail York, a political scientist at ASU, says that the School of Human Evolution and Social Change has been a welcoming environment for her and her family.

“Family is very well supported, generally, for people who are research intensive. And unlike what some of the articles have argued, that [faculty], especially women, have trouble balancing research and family, we have so many people here that are just doing phenomenal work and are mothers. For me, it was never a question that I could do good work and have children,” she says.

York also says she is surrounded by other families in the School of Human Evolution and Social Change. They were all happy to give her tips when she chose to take her 15-month-old daughter with her to Nepal.

“There are quite a few people here who have taken their kids into the field,” she says. “And so it was a little less intimidating to do. I was able to talk to people about the logistical things that are small but actually can be really stressful.”

Most surprising to York was discovering that having her daughter with her actually benefited her research. As a social scientist, part of her work necessitates talking to people and getting them to open up to her about their lives. Because of this, she thinks social science research in particular can actually be enhanced by the presence of a child.

“It opened up conversations with people about their households and how they were using the forest,” she says. “I think they saw me as maybe being more similar – me being a mother and having my daughter there enabled them to see me in a different light than if I was just a researcher coming in as an outsider.”

In fact, York’s daughter became something of a celebrity amongst the Nepalese with whom she worked.

“For a while as I was going and talking to different people in the village, we had this trail of people following us just wanting to catch a glimpse of her. It was pretty fun,” she says.

The role of icebreaker and diplomat is one that my brother and I also frequently played. Whether at home or abroad, we were representatives of our culture, and a constant source of conversation.

My mother comments that having children in the field provided “a source of comic relief in the research setting,” and that “internal tensions typically experienced within a crew of researchers can be dissipated or relieved by the presence of children.”

Key to success

All of the parents I interviewed agreed that the biggest factors in successfully coordinating fieldwork with family are support and planning. Elser, York and my parents had spousal help while in the field.

“I don't think I could have done it without my husband or setting up local childcare,” says York. My mother also commented that the experience of a single parent researcher might be very different from her own.

“Having two parents enabled us to work together as a team to resolve family and group issues, as there was one person usually freed up to handle one or the other. A single parent researcher, with children, will face different challenges, and may have to find different ways to address these challenges,” she says.

Being adequately prepared is also crucial. York prepared by consulting other researchers about the logistical challenges she would face in bringing a toddler into the field, such as insurance and what to pack.

Families need to be psychologically prepared as well as logistically. As my mother notes, if you are working with a crew and you bring your family, your family will be “on public display 24/7.” Despite these challenges, everyone I interviewed believes that bringing their children with them was a rewarding experience for all involved.

Tim Elser comments, “It's hard to imagine that there would have been a substantially better way for me to have spent my summertime,” and I know that neither my brother nor I would have traded those trips for anything.

Written by Erin Barton, Office of Knowledge Enterprise Development