Early humans had 'jaws of steel'

Computer simulation shows early humans had jaws to eat diet of hard seeds and nuts

Your mother always told you not to use your teeth as tools to open something hard, and she was right. Human skulls have small faces and teeth and are not well-equipped to bite down forcefully on hard objects. Not so of our earliest ancestors, say scientists. New research published in the February 2009 issue of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences reveals nut-cracking abilities in our 2.5-million-year-old relatives that enabled them to alter their diet to adapt to changes in food sources in their environment.

Mark Spencer, an Arizona State University assistant professor, and doctoral student Caitlin Schrein in ASU's School of Human Evolution and Social Change, are part of the international team of researchers who devised the study featured in the article "The feeding biomechanics and dietary ecology of Australopithecus africanus." Using state-of-the-art computer modeling and simulation technology - the same kind engineers use to simulate how a car reacts to forces in a front-end collision - evolutionary scientists built a virtual model of the A. africanus skull and were able to see just how the jaw operated and what forces it could produce.

"We started with a CT scan of a skull that is one of the most complete specimens of A. africanus that we have," said Spencer, researcher in ASU's Institute of Human Origins and a lead investigator on the project, which was funded by the National Science Foundation and European Union. This would be a later ancestor of Lucy - STS5 - who is affectionately known as "Mrs. Ples." The skull, discovered in 1947, has struts on the side of the nose, but no teeth. "We meshed those data with another specimen with teeth to make the virtual model of the bone and tooth structure.

"Then we looked at chimpanzees, who share common features with Australopithecus, and took measurements of how their muscles work and added that to the model. We were able to validate this model by comparing it to a similar model built for a species of monkey called macaques," Spencer explained.

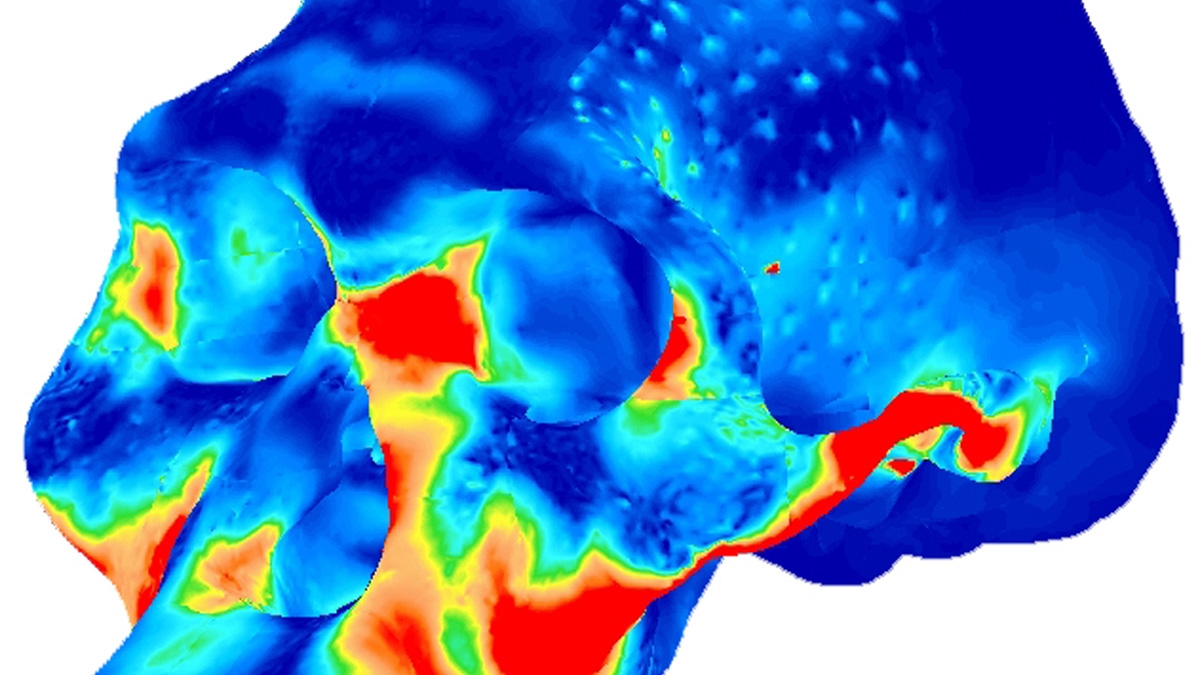

The result - a rainbow colored virtual skull that illustrates forces absorbed by the cranial structure in simulated bite scenarios and how their unusual facial features were ideally suited to support the heavy loads of cracking hard nuts.

"It was like watching ‘Mrs. Ples' come to life," Spencer said.

"This reinforces the body of research indicating that facial specializations in species of early humans are adaptations due to a specialized diet," said Spencer. "The enlargement of the premolars, the heavy tooth enamel and the evidence now that they were loading forcefully on the premolars suggest the size of the objects were larger than the previously hypothesized small seeds and nuts.

"These ‘fall back' foods - hard nuts and seeds - were important survival strategies during a period of changing climates and food scarcity," he added. "Our research shows that early, pre-stone tool human ancestors solved problems with their jaws that modern humans would have solved with tools."

The Institute of Human Origins in ASU's College of Liberal Arts and Sciences is renowned for its ground-breaking research on our earliest human ancestors. Don Johanson, the institute's founding director and discoverer of "Lucy," recently completed a new book co-authored with Kate Wong, writer and editor at Scientific American. Due to hit the shelves in March, the book "Lucy's Legacy: The quest for human origins" picks up where Johanson's previous work, "Lucy: The beginnings of humankind," left off, exploring the latest thinking on human species evolution and the current state of paleoanthropology.