Does religion turn weak groups violent?

Although David was famously successful at slaying Goliath, most people wisely avoid picking fights with more-powerful opponents.

But new research by a team of Arizona State University faculty has uncovered one factor that increases the likelihood that weak groups will engage in conflict with stronger groups, despite the likelihood of defeat. That factor is religious infusion, or the extent to which religion permeates a group’s public and private life.

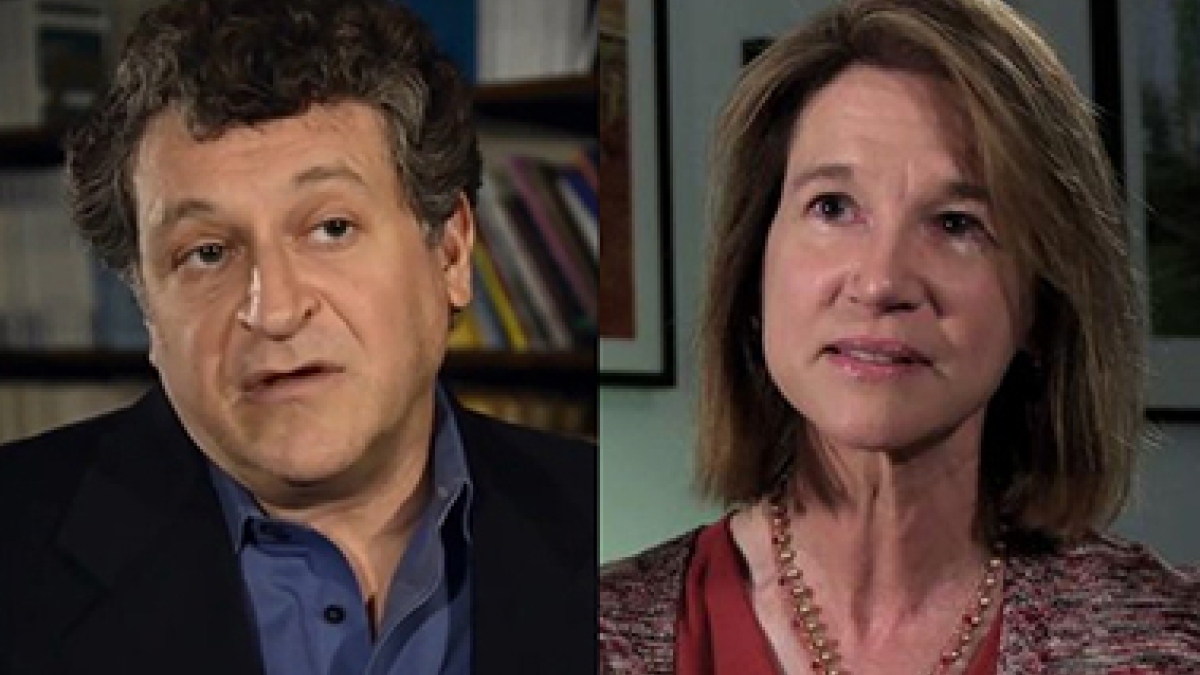

“Under normal circumstances, weak folks don’t try to beat up on stronger folks,” says Steven Neuberg, a psychology professor at ASU and the lead researcher on the project. “But there’s something about a group being religiously infused that seems to make it feel somewhat invulnerable to the potential costs imposed by stronger groups, and makes it more likely to engage in costly conflict.”

Their findings are published in the January issue of Psychological Science, the highest ranked empirical journal in psychology. Their work was also written about in the Huffington Post last summer.

The study Neuberg and his team undertook, part of the Global Group Relations Project, spanned five continents and included nearly 100 sites around the globe. The countries included in the project together account for nearly 80 percent of the world’s population.

“Our sites include the most populated countries of the world – China, India, USA, Brazil – as well as a wide range of others,” says Carolyn Warner, an ASU political science professor and a co-principal investigator on the project. “This breadth and diversity is rarely the case in studies of religion and conflict.”

Most research on group conflict employs one of two methods – the case study, which closely examines a particular location or situation in which conflict occurs – or a quantitative analysis of data pulled from existing studies.

For this project, researchers recruited a large, international network of social scientists with expertise on the sites selected for study. These “expert informants” responded to an Internet survey, answering a wide range of questions on a host of social, political, religious and psychological variables about the groups being studied.

Neuberg and his team examined the data to learn how religion might shape intergroup conflict around the world. They focused on two factors known to increase conflict: incompatibility of values and competition for limited resources.

They found that religious infusion was an important factor in predicting conflict in both situations. In cases where two groups held incompatible values, the groups tended to exhibit increased prejudice and discrimination against one another only if religion permeated their everyday lives.

More surprising, however, is the finding on how religious infusion affects groups competing for limited resources and power. Only the disadvantaged groups that are religiously infused are more likely to engage in violence.

“That’s a surprising finding, because the advantages and power held by the other groups should deter the weaker groups,” says Neuberg. “Remember, these weaker groups are likely to get clobbered, at least in the short term.”

Disadvantaged groups, as defined in the study, are those lacking access to sufficient food, water and/or land, as well as political power and educational and economic opportunities.

Religious infusion is not tied to specific religions or sets of beliefs. Any religion can be highly infused in a particular society.

“What we don’t want people to walk away thinking,” says Warner, “is that religious infusion is always bad or always makes group relations worse. Not all religiously infused weak groups engage in conflict. And high-power groups, when they’re religiously infused, aren’t increasing their aggression against low-power groups.”

So why would weak, religiously infused groups attack stronger powers? Some data from their project suggest that religious infusion may increase the motivation of weak groups to enhance their standing. Other data raise the possibility that religiously infused groups may have some advantages in mobilizing the resources they do have.

Warner and Neuberg will explore these possibilities, and the cause-and-effect relationship of their findings, in follow-up research.

“The amount of intergroup conflict in the world is costly and has huge and significant implications for national security and worldwide economic security,” says Neuberg. “To be able to better understand why this conflict occurs and predict it beforehand increases our chances of reducing its likelihood in the future. That should be important to all of us.”

The Global Group Relations Project grew out of an interdisciplinary faculty seminar series sponsored by ASU’s Center for the Study of Religion and Conflict, a research unit of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences that examines the role of religion as a driving force in human affairs. The center provided Neuberg and his colleagues with a seed grant to develop a proposal to the National Science Foundation, which funded the project.

Other faculty involved in the project included Ben Broome (Hugh Downs School of Human Communication), Roger Millsap (psychology), Thomas Taylor (School of Mathematical and Statistical Sciences), George Thomas (School of Politics and Global Studies), Michael Winkelman (School of Human Evolution and Social Change), and Juliane Schober (School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies). Graduate students who worked on the project included Stephen Mistler, Anna Berlin, Eric Hill, Gabrielle Filip-Crawford, Jordan Johnson, Hui Liu, and Prasun Mahanti.

Story by Barby Grant