CTI professor leads research for best practices in skill-transfer training

Military professionals are continuously finding new ways to improve their technology in order to ensure their missions are successful and completed at the most efficient level possible. Generally, the field of psychology is often unrelated to military technological advances, but one ASU psychology professor considers the contribution to be substantial.

Nancy Cooke, a professor in the Applied Psychology Department at the College of Technology and Innovation (CTI), is the science director for the Cognitive Engineering Research Institute on the Polytechnic campus. Cooke has been studying the collaborative dynamics of teams and how their interactions affect their functionality. Her research aims to measure a team’s cognition in order to find new ways to make teamwork more effective.

“Any group working toward a common goal can be considered a team: a basketball team, a military group, a surgical team,” Cooke said. “When we study how these teams communicate and reveal their group dynamics, we can potentially discover how to make that process an effective one.”

Part of Cooke’s research is studying the habits of Improvised Explosive Device (IED) detection experts and analyzing how they can best transfer their skills to novices through training. Considered vital to the military, IED detectors are responsible for remotely detecting explosive devices in an area. Detectors scan an area using satellite and video imaging in order to spot anything out of the ordinary and report it to ground officials.

With the support of research grants from the Air Force Research Lab, the project hopes to uncover cognitive underpinnings that demonstrate a marked difference in the detection abilities of experts versus the detection abilities of novices. Analysis of experts is expected to reveal ways to transfer expert skills to novices through training.

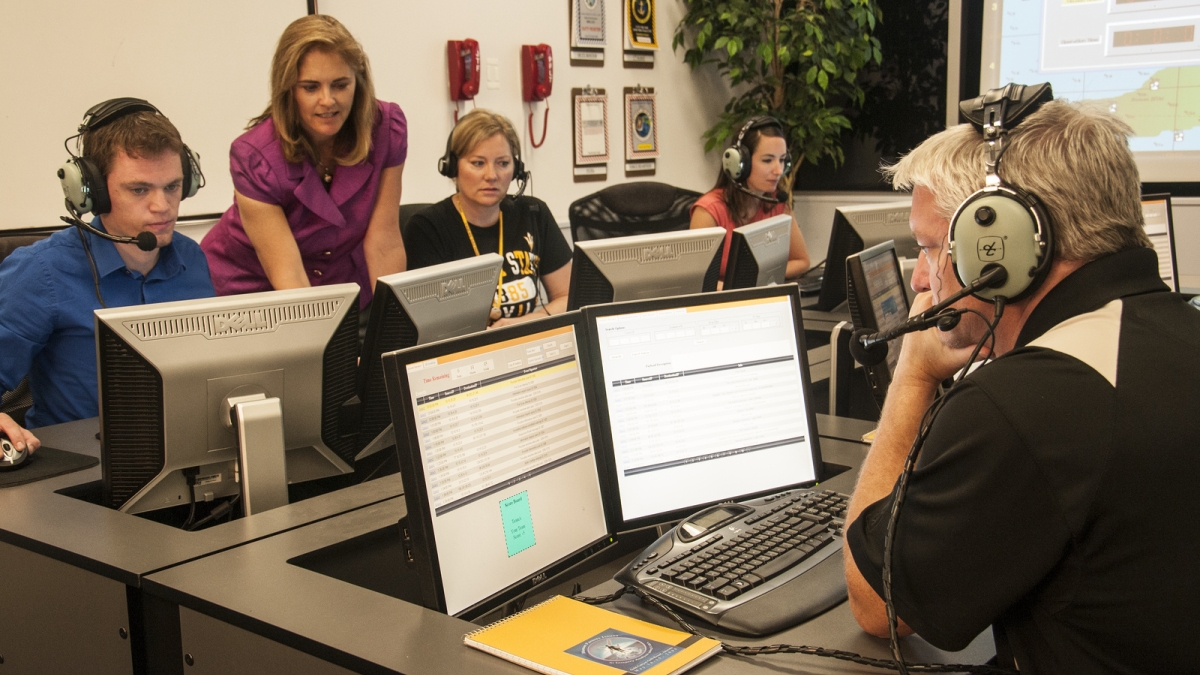

Participants are seated at a video screen where they are given various scenarios. Using eye tracking software, Cooke is able to verify what cues these experts are looking for and compare that to how novices are viewing an image.

“This work has the most potential to save lives because IEDs are not visible,” she said. “They are killing so many people, but they’re remotely controlled. Our work will hopefully improve how this training is occurring.”

Cooke says there will always be a need for IED detection experts because IED creators often find ways to hide an explosive device that can trick electronic IED scanners.

Cooke is also studying how to best train pilots for unmanned aerial systems (UAS), commonly known as drones. Currently, the Federal Aviation Administration allows limited UAS missions involving public interest, such as disaster relief, search and rescue, border patrol, military training and law enforcement missions, but the FAA is working to develop a path for safe integration of civil UAS into the airspace.

“There is such a need for UAS pilots, and I am studying the human factor side of UAS training which includes the design of workstations, integration of systems that include a human element and best practices for training pilots specific to this field,” Cooke said.

Experts suggest that the demand for UAS pilots will grow as the FAA begins integrating civil UAS flights into national airspace.

Written by Sydney B. Donaldson, College of Technology and Innovation