Chomsky discusses science, politics with ASU's Krauss

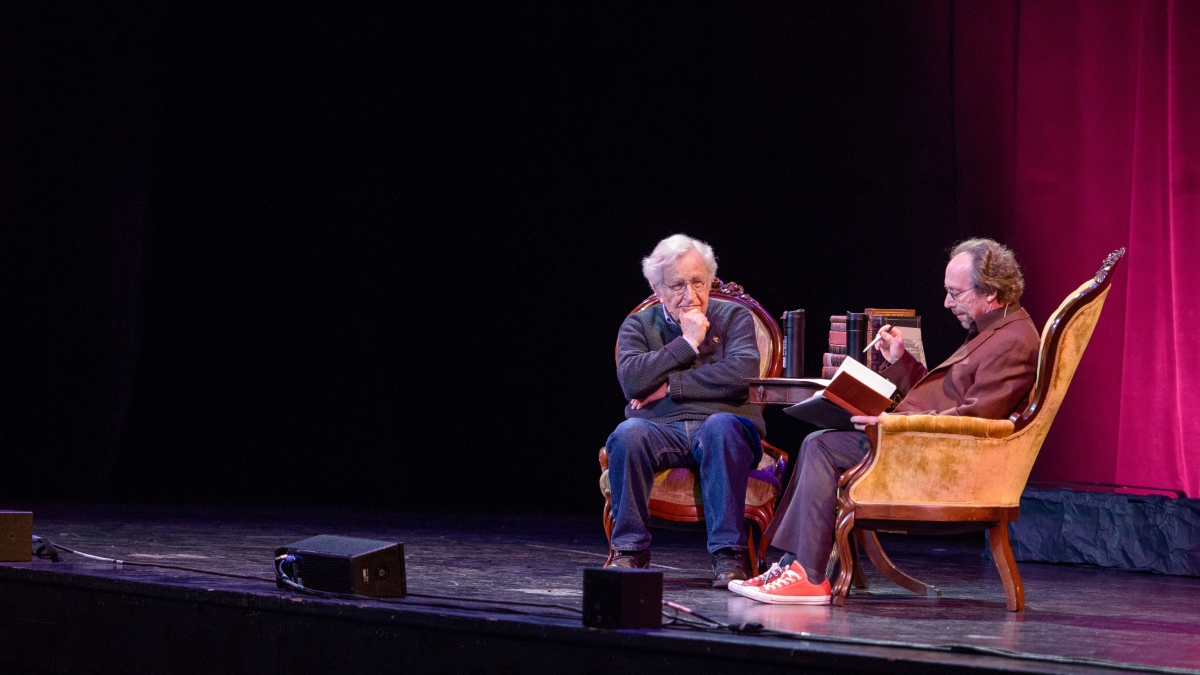

On March 22, intellectual giant Noam Chomsky took the stage at Arizona State University's Gammage Auditorium to thunderous applause from the sold-out audience. Physicist and ASU Origins Project director Lawrence Krauss joined him for the nearly three-hour discussion.

Krauss cited Chomsky and the physicist Richard Feynman as his two intellectual heroes. He went on to note that despite Chomsky’s prominence and enormous achievements, his ideas – so often against the grain of elite powers governing mainstream discourse – made him an outcast in almost all mainstream media, too subversive to expose the fragile public to.

Undaunted, Chomsky has informed and enlightened a vast global audience through countless interviews and debates, (most outside the boundaries of the mainstream media), as well as innumerable articles and over 100 books.

Language roots

Chomsky said that what drew him to linguistics was the idea that language offers access to the human mind. He outlined a history that regards language as the unique and distinctive property of human beings, setting our species apart from other animals. Here he stressed a fundamental point, central to some of his core ideas in linguistic theory, namely that analysis of the structure of particular languages is far less important than the unique human capacity to use language in a flexible, creative and unbounded manner, an innovation altogether different from animal communication.

He added that “probably 99 percent of your language use never gets expressed – it’s internal,” and emphasized language’s primary function, not as vehicle of communication but rather, an indispensible tool of human thought.

Language evolution

Chomsky was highly critical of writings on the evolution of language.

“Languages may change, but they don't evolve,” he said. “What evolves is the capacity for language and that’s a crucial difference. We know a few things about the evolution of this capacity, but really very little. One thing we do know is that the capacity for language is virtually identical across all humans. ”

As far as we can tell, Chomsky said, no further evolution in language capacity has taken place in the ensuing 50-60,000 years since early humans migrated from east Africa, an occurrence coinciding with the advent of complex tools, advanced social organization and symbolic representation.

“What developed in that brief window must be something simple and invariant – the same for all languages,” Chomsky said, a reference to his ideas about a Universal Grammar.

Politics by other means

Krauss urged Chomsky to speak about the highly developed modern systems of propaganda that obscure unpleasant realities and seek to prevent the public from discovering the true nature of state policy, thereby becoming engaged citizens. The topic is one Chomsky has devoted considerable thought to, including full-length works like "Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media" (Pantheon Books, 1988).

Bringing the issue of violence up to the present day, Chomsky echoed the widespread alarm about the rise of the Islamic State, “a monstrous development.” He credited the United States with helping to create this Frankenstein, both by fanning the flames of sectarian violence following America’s destruction of Iraq and lavish support for the chief funding agency for violent Islamic extremism, namely Saudi Arabia.

Where are we heading?

In closing remarks, Chomsky and Krauss examined the perils threatening human survival and prospects for addressing them before it’s too late. Chomsky insisted the world remains at grave risk of planetary annihilation due to nuclear weapons and is also heading toward an environmental abyss – the result of unchecked climate change coupled with massive degradation of the planet’s other life-sustaining systems.

Chomsky finished on a hopeful chord: “We as individuals have the capacity to modify and overcome the institutions that are driving us to disaster,” he said. “For those who have the technical and scientific knowledge, there’s a very high imperative, but the same applies to every one of us.”

Krauss echoed this by suggesting this was the new "Responsibility of Intellectuals," hearkening back to Chomsky’s famous 1966 essay by that name.

Following the discussion and questions from the audience, both speakers were available for a book signing, as the evening drew to a close.