Rattlesnakes and rain: A desert mystery

ASU engineer and evolutionary ecologist team up to solve slippery question

Summer monsoon rains have finally come to the Sonoran Desert. At first it’s a soft patter as rain drops raise puffs of dust, then the water comes quicker and quicker until it’s falling with the staccato of a typewriter on deadline.

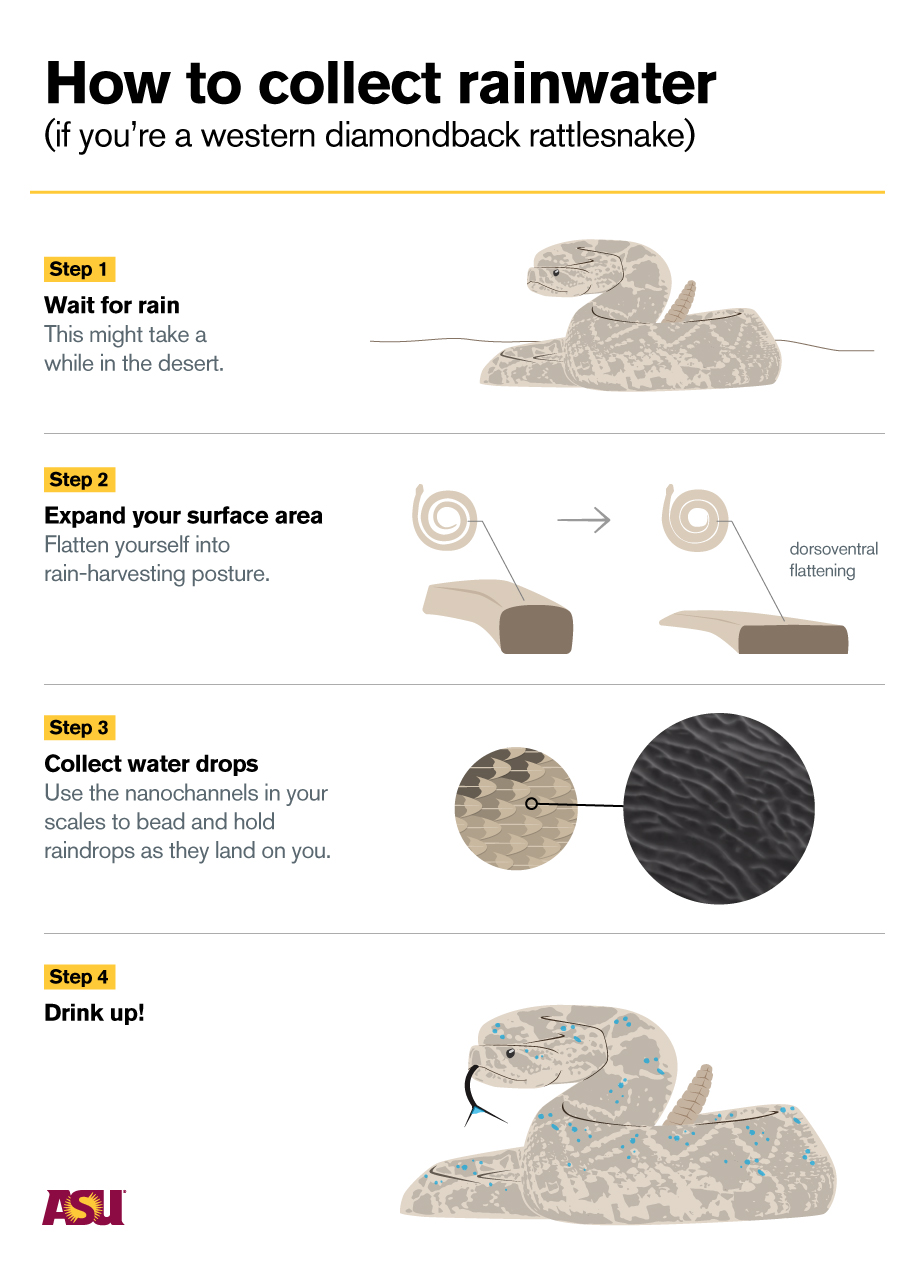

A rattlesnake undulates from its den and coils on a rock. Its body flattens out. Rain drops stick to its body and slide down into channels in its skin. The snake turns its head around and begins drinking.

“They use their body as a bowl,” said Konrad Rykaczewski, an engineer at Arizona State University.

Water droplets stick to their scales. But why would the droplets stick? Nothing sticks to snakes.

That was the question Rykaczewski and evolutionary ecologist Gordon Schuett set out to answer. Their discovery was highlighted in a recently published paper, which they discussed Wednesday in a Nature@Noon talk at ASU’s Biomimicry Center.

The Biomimicry Center at ASU addresses a variety of sustainability challenges using methodologies inspired by natural systems through research, education and outreach activities. By asking the question, “How would nature do this?”, biomimics around the world are creating products, processes, companies and policies that are well adapted to life on Earth over the long haul. Examples include turbine blades designed like whale fins to reduce drag and stronger fiber optics produced like sea sponges.

Schuett, the science director at the Chiricahua Desert Museum, has studied diamondback rattlesnake behavior for 16 years. He has seen this behavior many times in the desert, including one winter where a large number of rattlers lay on a shelf outside a den drinking snow off their bodies. (They were radio-tracked. The chances of running into a sight like that by luck are slim to none.)

But how does it work?

“We’re interested in the fundamental physics of why this happens,” Rykaczewski said.

Other snakes have been observed drinking rain from their bodies, but rain harvesting by rattlesnakes equates to survival in the Southwestern deserts, where temperatures can hit 122 degrees Fahrenheit and months can pass without rain. Rattlers can go 200 days without water. When it does rain, they need to make the most of it.

“If they’re spending the winter in a shelter, where are they going to get water?” Schuett asked.

“Imagine standing in the rain and trying to collect enough water to survive,” Rykaczewski said. “Good luck.”

How does the texture of rattler skin contribute to rain harvesting? Rykaczewski bored down on the scales of adult western diamondback rattlers and, for comparison, those of desert kingsnakes and Sonoran gopher snakes. The two latter species don’t harvest rainwater.

Rattlesnake skins are rough and highly water-repellent. They have a high contact angle and a dense labyrinthlike nanotexture. Grooves and channels run down the scales. The texture slows water down and collects it.

“Here we have another perspective of why snakes shed frequently,” Schuett said. “It’s to keep the nanochannels as efficient as possible.”

The Biomimicry Center funded the study. The next Nature@Noon lecture will be held on March 25.

Top image by Alex Cabrera, Media Relations and Strategic Communications.

More Science and technology

ASU author puts the fun in preparing for the apocalypse

The idea of an apocalypse was once only the stuff of science fiction — like in “Dawn of the Dead” or “I Am Legend.” However these days, amid escalating global conflicts and the prospect of a nuclear…

Meet student researchers solving real-world challenges

Developing sustainable solar energy solutions, deploying fungi to support soils affected by wildfire, making space education more accessible and using machine learning for semiconductor material…

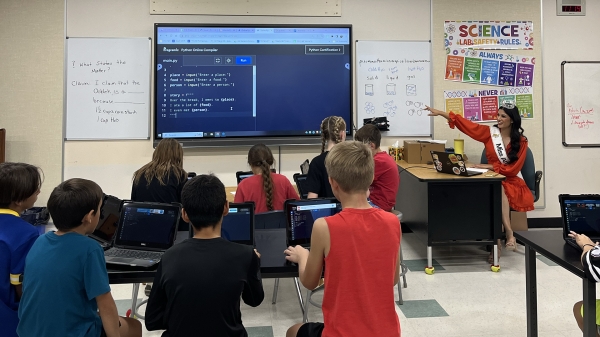

Miss Arizona, computer science major wants to inspire children to combine code and creativity

Editor’s note: This story is part of a series of profiles of notable spring 2024 graduates. “It’s bittersweet.” That’s how Tiffany Ticlo describes reaching this milestone. In May, she will graduate…