New satellite system can map tropical forest carbon emissions

High-resolution carbon monitoring will be able to quantify the cost of deforestation

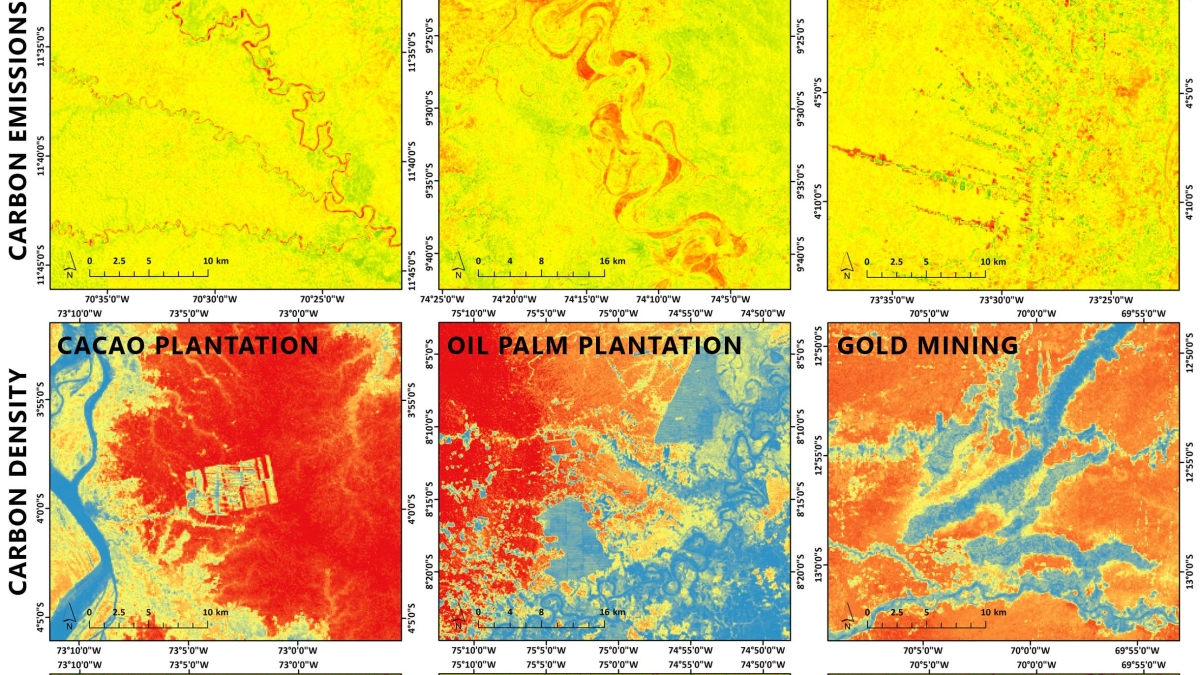

Examples of changes over time in aboveground carbon density estimates between 2012 and 2017 in Peru. Various patterns are shown, from intact forests and river meandering, to human-dominated sources of carbon emissions, represented by deforestation along the Iquitos-Nauta road in Loreto, aggressive cocoa plantation expansion near Iquitos, oil palm plantations near Pucallpa, Ucayali, and expansion of gold mining activities in Madre de Dios.

For the first time, scientists have developed a method to monitor carbon emissions from tropical forests with an unprecedented level of detail. The approach will provide the basis for developing a rapid and cost-effective operational carbon monitoring system, making it possible to quantify the economic cost of deforestation as forests are converted from carbon sinks to sources. The study was published in Scientific Reports on Nov. 28, 2019.

Researchers at the Arizona State University Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science (GDCS) worked with satellite imagery from Planet Inc., an Earth-imaging company based in San Francisco, to develop maps of carbon stocks and emissions for Peru by combining millions of hectares of airborne laser measurements of canopy height with thousands of high resolution Planet Dove satellite images.

“We combined advanced remote sensing data and machine learning algorithms to estimate aboveground carbon stocks and emissions throughout the highly diverse ecosystems of Peru," said Ovidiu Csillik, lead author of the study. "Our approach will serve as a transformative tool to quantify and monitor climate change mitigation services provided by tropical forests.”

Using this technology, the researchers were able to estimate a total of 6.9 billion metric tons of carbon stored aboveground in Peru’s diverse ecosystems, of which only 2.9 billion tons are found in protected areas. However, they also found that between 2012 and 2017, 80 million metric tons of new carbon were sequestered aboveground in forests, but another 96 million tons were emitted via logging, deforestation and other factors. This resulted in a net loss of forest carbon in the five-year study period.

The new high-resolution monitoring approach revealed the precise location of these carbon emissions, for example, in areas converted from forest to oil palm and cacao plantations, agricultural and urban areas and gold mines.

“Our study powerfully demonstrates a new capability to not only measure forest carbon stocks from space, but far more critically, to monitor changes in carbon emissions generated by a huge range of activities in forests,” said Greg Asner, director of GDCS and co-author of the study. “The days of mapping forests based simply on standing carbon stocks are behind us now. We are focused on carbon emissions, and that’s precisely what is needed to mitigate biodiversity loss and climate change.”

This research was supported with funding from Erol Foundation and Global Conservation.

More Science and technology

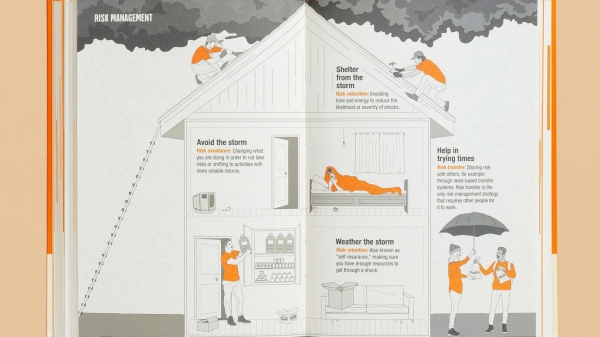

ASU author puts the fun in preparing for the apocalypse

The idea of an apocalypse was once only the stuff of science fiction — like in “Dawn of the Dead” or “I Am Legend.” However…

Meet student researchers solving real-world challenges

Developing sustainable solar energy solutions, deploying fungi to support soils affected by wildfire, making space education more…

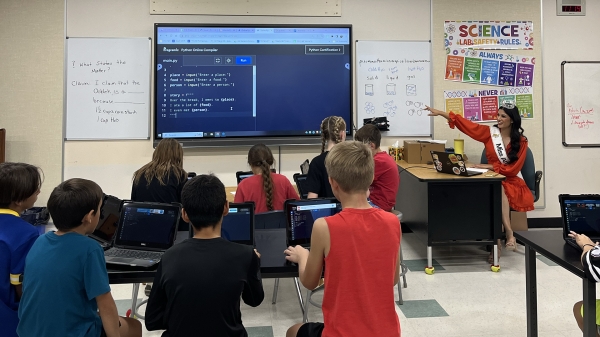

Miss Arizona, computer science major wants to inspire children to combine code and creativity

Editor’s note: This story is part of a series of profiles of notable spring 2024 graduates. “It’s bittersweet.” That’s how…