Studies probe the social communication challenges of aging with autism

ASU's Autism Brain Aging Laboratory works on studying age-related changes in adults with autism spectrum disorder

What makes us who we are and how does that change as we get older?

It’s a question Arizona State University College of Health Solutions Assistant Professor B. Blair Braden has been asking since childhood, when she spent much of her time at the nursing home owned and operated by her family.

Later, her focus narrowed to how aging affects individuals with autism after spending time with students in her sister’s special education class.

And just this month, Braden published a series of related studies in the scholarly journal Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders — two of which will be featured in the journal’s special issue on aging with autism — that probe the specific question of how social and verbal fluency change as individuals with autism age.

Braden and her team in the Autism and Brain Aging Lab found that older adults with autismBraden notes that a large percentage of people on the autism spectrum are nonverbal. The studies referred to in this story included only individuals on the spectrum who have verbal abilities. report more social communication difficulties than younger adults with autism, however verbal fluency does not appear to become more difficult with age. Using brain scans, they were also able to deduce that areas of the brain related to social communication, cognition and executive functions thinned more quickly with age in adults with autism than those without.

Video by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

“People with autism have a lot of these cognitive struggles and brain communication patterns that look more like what we know happens with aging,” Braden said. “So that really informed our hypothesis and, in this case, on a brain level, it panned out … and it correlated with their social communication difficulties. So we really feel like we have preliminary evidence for what the brain change is that is explaining the difficulties.”

In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate the number of children who have been diagnosed with autism at 1 in 59. That means, within a decade or two, there will be a population of about 1 million adults on the spectrum. Over their lifetime, treatment expenses, lost wages for themselves and lost wages for their caretakers can exceed $2 million.

“So there’s also a tax dollar reason to want to find effective ways of helping adults with autism integrate into society,” Braden said.

Robert Behr, a participant in Braden’s studies who was diagnosed with high-functioning autism in his mid-50s, has a master’s degree in computer science and a career as a software engineer. Despite his successes, he still sometimes struggles with the social aspect of communication, which he says has led to many a misunderstanding with girlfriends.

Fellow study participant Susan Golubock, also diagnosed with high-functioning autism later in life, has had somewhat less trouble in that area, thanks in part, she believes, to none other than Shirley Temple. As a child, Golubock learned to model her tone of voice and facial expressions after the saccharine child actor, which helped her master those nonverbal communication cues crucial to positive social interactions.

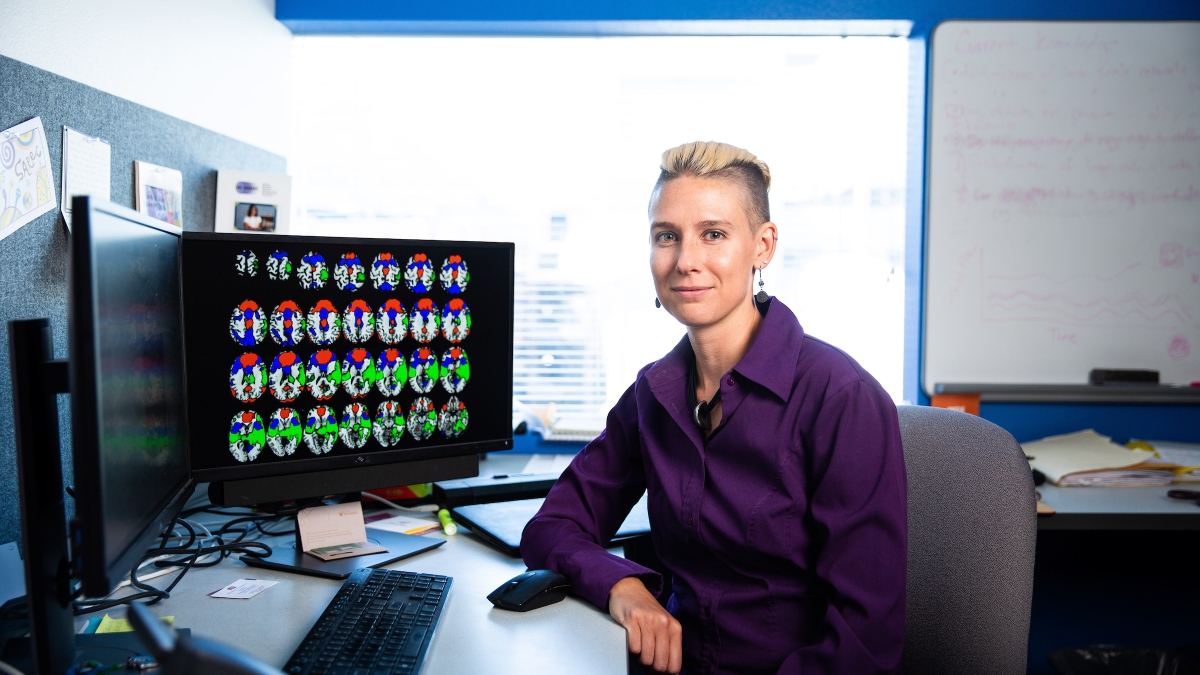

Assistant professor B. Blair Braden works with students in her lab to examine parts of the human brain as well as sheep brains in the Autism Brain Aging Lab in July 2018. Braden's lab works on studying age-related changes in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

“I felt these were things that people expected of me and I didn't know how to do them, so I taught myself,” she said.

Even so, Golubock still finds social situations overwhelming. When one researcher asked her what she learned about her friends on a recent lunch date, she had an epiphany.

“It was like, I had no clue that's why people did it (spent time interacting socially),” she said. “I was supposed to be learning something about them? With all that noise going on, and focusing on not aspirating and all the other things I had to focus on?”

That Golubock is successful at appearing outwardly adept in social situations while inwardly she feels stressed is evidence of a phenomenon known as camouflaging.

“Camouflaging is still a working definition,” Braden said. “It’s only something that's been talked about a lot in the last couple of years, but it’s the discrepancy between someone’s internal experience and their external output. … And that discrepancy is greater for women.”

Such nuances are good examples of why Braden is working diligently to ensure more women are involved in this kind of research.

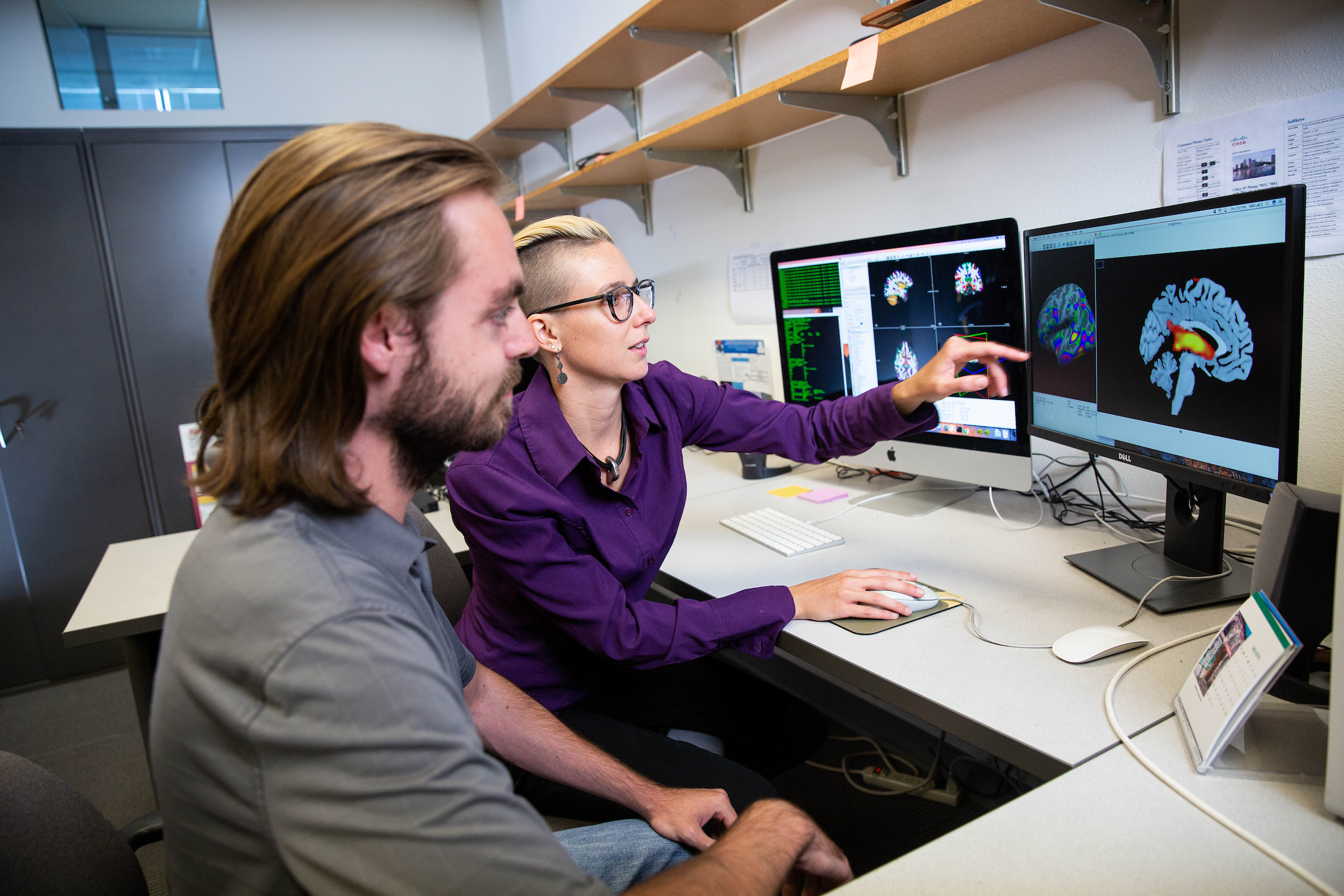

Assistant professor B. Blair Braden works with doctoral candidate Cory Riecken in the Autism Brain Aging Lab. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

Considering that Behr and Golubock, two adults with autism who are on the high-functioning end of the spectrum, still experience communication challenges underscores the importance of interventions for people on the lower-functioning end of the spectrum.

However, both caution that such interventions must be carefully thought out.

Behr believes having grown up “in the wild,” as he phrases it — meaning they weren’t diagnosed until later in life, and as such, didn’t receive therapy or behavioral intervention as children — puts them at an advantage over children today because, while he and Golubock had to think hard about social interaction and figure it out on their own, children today are simply following instructions on how to act without thinking or understanding why.

Braden is taking their concerns into consideration as she works to design new types of interventions that adapt tools used to teach social communication skills to teens and young adults with autism to make them feasible for people who are experiencing age-related decline in that area.

“I just think it’s important for everyone to know what to expect when they get older, especially if there’s reason to believe aging may affect you differently,” she said.

Braden and her team are always enrolling new adults with autism and neurotypical participants for studies.

Top photo: B. Blair Braden's lab, the Autism Brain Aging Laboratory, works on studying age-related changes in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

More Science and technology

ASU receives 3 awards for research critical to national security

Three researchers in the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering at Arizona State University have received grant awards under the Defense Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research, or…

Celebrating 34 years of space discovery with NASA

This year, NASA's Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is celebrating its 34th anniversary of the world's first space-based optical telescope, which paved the scientific pathway for NASA's James Webb Space…

Making magic happen: Engineering and designing theme parks

The themed entertainment industry is widespread and diverse, encompassing everything from theme parks to aquariums, zoos, water parks, museums and more. The Theme Park Engineering and Design…