From the rise of artificial intelligence to the future of water, Arizona State University faculty and students discussed a slew of science topics at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

AAAS is the world’s largest science and technology society, and its annual meeting draws thousands of scientists, engineers, educators, policymakers and journalists from around the world.

This year’s meeting was held Feb. 14–17 in Washington, D.C. The 2019 meeting theme, “Science Transcending Boundaries,” explored ways science is bringing together people, ideas, and solutions from across real and artificial borders, disciplines, sectors, ideologies and traditions.

One of the biggest ways ASU research is emblematic of this year’s AAAS meeting theme, is in its transdisciplinary approach to solve pressing world problems — from interplanetary and global scale efforts down to the level of each person, such as new platforms to enable more personalized learning and success of each student.

Faculty and students presented their ideas and results on a range of topics using several science communication formats, including formal presentations, rapid fire talks, organizing sessions and poster sessions. Here are a few highlights from the AAAS meeting.

Exceptional student scholars tackle worldwide issues

Several ASU schools, department and researchers are committed to making a difference to human-caused climate change, known as the Anthropocene epoch. But this is not just an academic exercise — in the Gulf Coast, for example, it is now affecting people in their own backyards. A USGS report estimates that Louisiana, which experiences more coastal wetland loss than all other states in the conterminous United States combined, lost more than 2,006 square miles of land from 1932 to 2016.

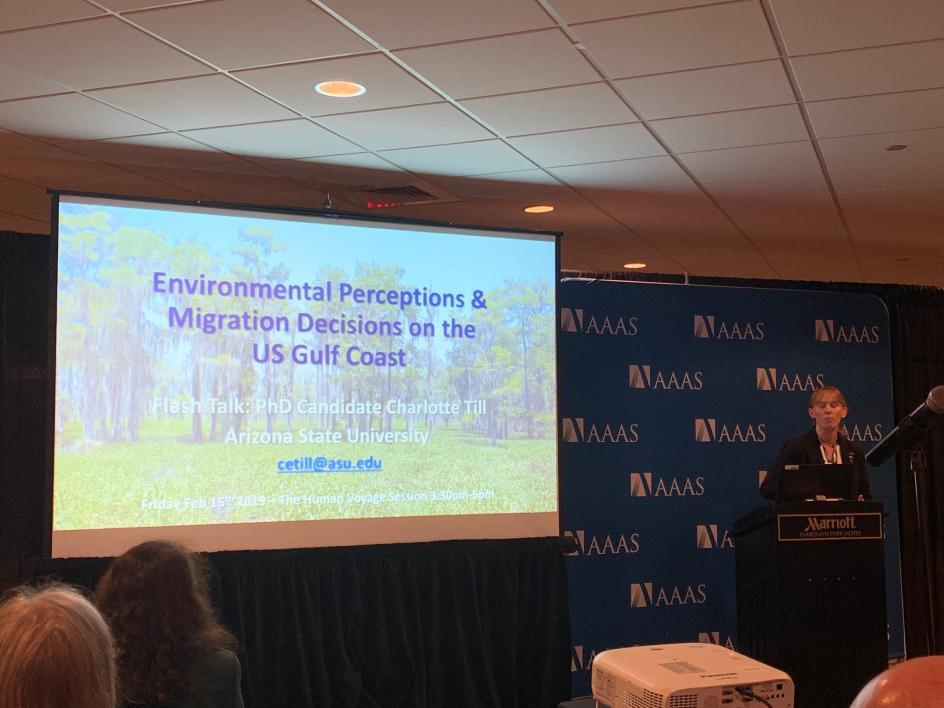

“Every hour of every day, an area the size of two football fields goes underwater,” said Charlotte Till, an ASU Fulbright Scholar and graduate research associate in the School of Human Evolution and Social Change. “There are about 600 million Americans that live in the path of hurricanes. There is about 30 percent of the population that lives directly adjacent to an ocean (within a mile of the ocean). People will need to move if they are losing two football fields of land every hour every day.”

Till gave an AAAS flash talk on how U.S. Gulf Coast residents have grappled with decisions on whether to remain in, or leave, their homes in the wake of hurricanes and the predicted sea level rise with the warming of the world’s oceans.

For the residents she surveyed, their environment meant to them concepts like “home, family and community,” according to Till. “Guess what. They don’t want to go.”

Till will continue her dissertation work this summer to further explore how people living on the front lines of climate change perceive their environment, and their own futures as the risks increase with environmental change in their own backyards.

School of Sustainability researcher Veronica Horvath addressed the future of the American West’s most precious resource, water. Horvath, an Arizona State University Master of Science in sustainability student and Decision Center for a Desert City research assistant, is a first-place awardee of the 2018 Central Arizona Project Award for outstanding water research.

“As a researcher, I am curious to understand how cities address freshwater resources, long-term planning for sustainability and water governance," Horvath said.

At AAAS, she presented on a Decision Center for a Desert City 2018 survey that explores residential perceptions on sustainable water management in Phoenix, Las Vegas and Denver. The survey focuses on the need for water management changes and support for specific strategies toward sustainability. Although there were many takeaways from the survey, she found interesting that a large portion of residents supported strategies such as wastewater being treated to drinking-water standards.

"It has been an amazing opportunity as a Decision Center for a Desert City research assistant to travel to AAAS on behalf of ASU and a research endeavor that has been years in the making," Horvath said. "Our results suggest that increased engagement to encourage personal responsibility for water issues and knowledge of how to get involved with water sustainability solutions can work on meeting the needs of urban water sustainability at the local level."

A recent publication in Sustainability Science includes the full research team who brought this extensive project to fruition: Abigail Sullivan, Eleanor Rauh, Amber Wutich, Dave White, Kelli Larson, Danielle Chipman and Krista Lawless.

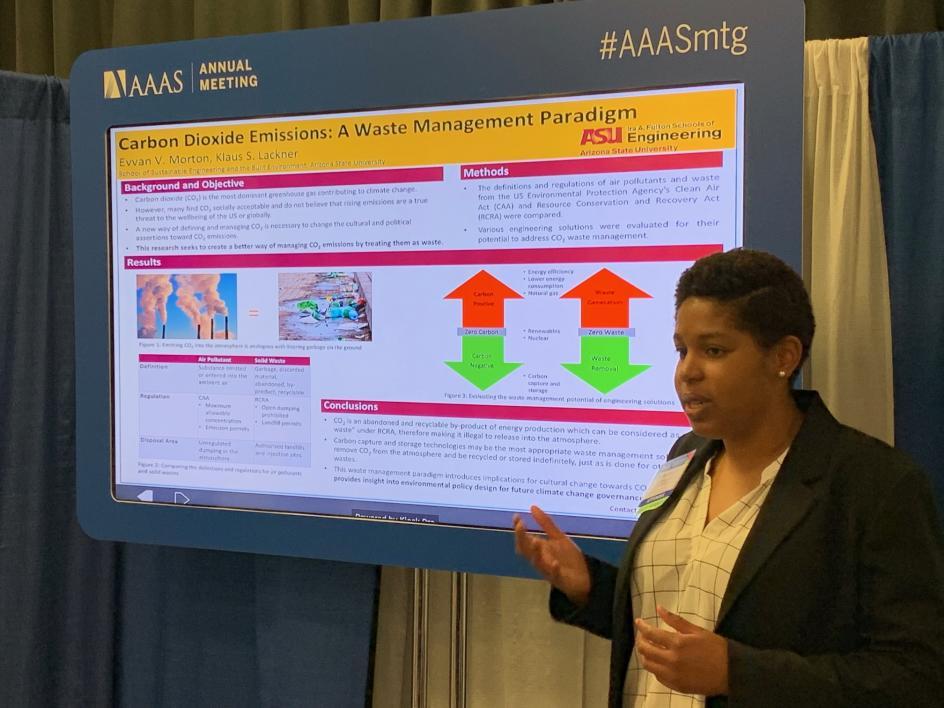

In addition to the land and water, there is also the future of the air we breathe, and how to best mitigate the most dominant greenhouse gas, rising carbon dioxide levels. When it comes to managing carbon dioxide levels in the air, Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering graduate student Evvan Morton thinks it may be best to start changing our policy mindset by flipping the conversation.

“It may be better to manage carbon dioxide emissions by treating these emissions as waste," Morton said. "If you thinking of CO2 as waste, you are literally littering the air like we do with garbage on the ground. What would that mean culturally and politically with how we perceive CO2 emissions and the environmental policies that we make?”

Morton, who is a graduate student thinking globally in mentor Klaus Lackner’s Center for Negative Carbon Emissions, explored this new paradigm in her talk.

Rather than relying on the EPA’s definition of air pollutants and regulatory policy under the Clean Air Act, the EPA may regulate CO2 differently if it is defined as a solid waste under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act.

“Carbon dioxide falls within this definition,” Morton said. “It’s a waste byproduct from combusting fossil fuels. It is also recyclable if captured.”

ASU is at the academic forefront of making carbon-capture technologies viable, and Morton, an engineer by training, wants to begin to link the technologies with changing policy. Along with the sustainable engineering doctoral degree she will earn within the next two years, Morton is studying to earn a graduate-level academic certificate in Responsible Innovation in Science, Engineering and Society from ASU’s School for the Future of Innovation in Society.

This new waste management paradigm not only has potential for a cultural shift in the way society thinks of CO2 emissions, but also future climate-change policy.

“What would happen if we say it is illegal to dump CO2 into the air? Our atmosphere is already clogged, so perhaps there is no better way if we are going to get past the 1.5 degree Celsius–[global warming temperature change] allowable target,” said Morton.

The rise of AI and self-driving cars

Whether you buy in to the hype or fear, AI is everywhere these days.

To ground folks into why this is the case, Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering Professor Subbarao Kambhampati gave a tour de force overview on the last four decades of AI during a standing-room-only AAAS session on “The Rise of AI: Status, Prospects and Thresholds.”

“AI is bigger than you suppose,” Kambhampati said. “And it’s bigger than you can suppose. Everybody is falling over each other to say their consumer products have AI in it — even electronic toothbrushes. But naysayers say it will destroy the world.”

Kambhapmpati says one of the key reasons AI has become the topic de jour is to understand the contrast between the development of human intelligence and artificial intelligence. In human development, a baby first shows perceptual intelligence, recognizing the faces and voices of their parents; then emotional intelligence, managing anger and tantrums; then social intelligence of interacting with others; and finally, reasoning and cognitive intelligence.

“If you think about AI’s progress toward intelligence, AI almost went in the opposite direction,” Kambhampati said. “Back in the 1980s, it was rule-based systems. In the 1990s, reasoning, and Deep Blue vs. Kasparov in chess, and now, perceptual intelligence with speech, language and image. Perceptual abilities made AI come to us. And it leads to all sorts of off-the-wall worries that people make up in their own lives.”

That contrast explains a lot of what has been developing in AI. We could program the computers about how to play chess, and the rules of companies. But we could not program the computers themselves, we had to let them learn, and slowly recognize images and speech. And these perceptual learning aspects of AI are only as good as the algorithms programmed by people, who can be prone to biases.

“Intelligence is the ultimate dual-use technology, and it can be used for good and bad. We can generate fake videos, fake text, and in the future, this may boggle the mind,” Kambhampati said.

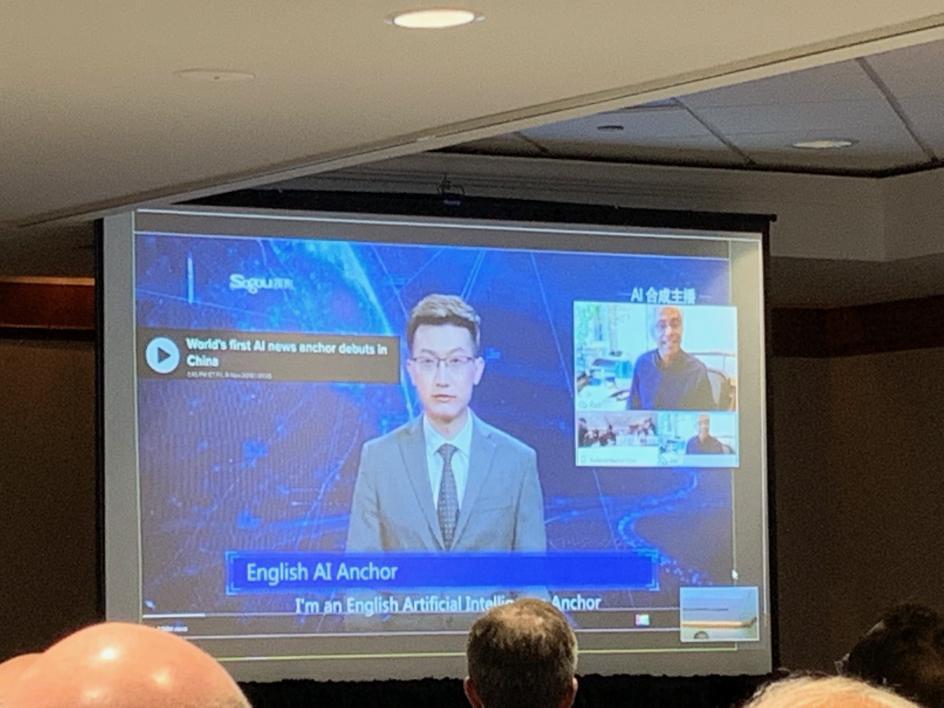

Just this year, China has developed the first AI English anchor who provides real fake news — but don’t buy into the concept of killer AI bots quite yet.

“AI systems are now doing pretty well on perceptual tasks, but we are still far from real intelligence. AI technology is here to stay, but there are significant positive impacts it can bring,” he said.

Kambhampati joked that above all, percepts AI needs a new type of serenity prayer to live by: “Humans, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot, use data to learn the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference!”

Future of driverless cars

One game-changing societal application for AI is autonomous vehicles. Recently named as a top 10 academic think tank, the Washington, D.C.-based ASU Consortium for Science Policy and Outcomes (CSPO) — under the leadership of faculty members Mahmud Farooque and Jason Lloyd — organized a conference on the future of driverless cars, which has the potential to eliminate half of current jobs. In 2017, they helped launch the first project focused on autonomous vehicle citizen forums that will soon be expanded to 25 cities in the U.S. and Europe.

“We deal a lot with emerging technologies, and there are uncertainties on the technology side and uncertainties on the societal-impact side,” Farooque said.

The first findings of the study were reported at AAAS from University of Maryland colleague David Tomblin, who showed that citizens cared most about how autonomous vehicles would impact their families and social lives in surveys of citizens from both a big city, Baltimore, and rural Cumberland, Maryland.

“The most important thing were the social issues,” Farooque said. “And it flipped so quickly, like, ‘I’m going to get that time back that I take my parents to the doctors, my kids to the soccer practice. But at this same time, that’s my only contact with them during the day. I’m going to lose that.’ And what if they go to the casino instead of the doctor’s office? Now, you can see that the hopes and the fears are very closely linked, and it’s all about societal things, not necessarily the technology side.”

While Baltimore citizens grappled with issues like free time, the rural residents of Cumberland saw AI as a huge infrastructure opportunity to become more connected.

“They were more hopeful in the rural areas because they see that they are currently disconnected from mobility choices,” Farooque said. "There is one Uber driver in that town. If it’s automated, I can reconnect. But would it may certain problems worse? We have an opioid crisis. With all of these cars without drivers, we don’t know where they are coming and going.”

According to Farooque, the CSPO teams’ autonomous vehicle survey results could be summarized into three main issues.

“One bucket is autonomy: How much control do I want to give, and how much control do I want to retain? Number two is the economy and jobs: Am I going to lose, or am I going to gain? What’s going to happen? And number three is safety, but not just safety about saving lives, but is it going to be safe for me to get in one? What’s going to happen in my everyday life?”

The ASU CSPO-led large societal forums on autonomous vehicles will take place in Phoenix, Washington and Boston in May. Thereafter, it will expand to 22 other cities in the summer.

AAAS 2019 honorees

At the conference, Fulton School of Biological and Health Systems Engineering faculty Samira Kiani became the very first ASU recipient of the 2019–2020 Alan I. Leshner Leadership Institute Public Engagement Fellows, given to 10 researchers in this year’s theme of human augmentation. These scientists and engineers were chosen for having demonstrated leadership and excellence in their research careers and an interest in promoting meaningful dialogue between science and society.

“The topic I’m working on is very timely with engaging the public,” Kiani said. “There are so many implications with CRISPR, gene editing and how it is changing the future. And it’s not just in health, but every aspect of our future: climate, food, everything.”

During her fellowship year, Kiani wants to have the opportunity to extend the reach of her documentary, “Code of the Wild.” In collaboration with director and filmmaker Cody Sheehy (Rhumbline Media), Kiani will also work on an initiative called Tomorrow Lab, which aims to foster a creative and engaging dialogue about rapidly developing genetic technologies, how they transform the future and what it means to be human in these reimagined societies. The online learning educational platform will bring together all of the information that exists on gene editing and CRISPR into a highly appealing visual learning tool.

“I thought this was the perfect opportunity to use filmmaking and the creative arts to bring to the forefront the type of conversations that will eventually come up," she said. "As we go forward, more and more conversations are needed because of the recent Chinese gene-edited babies and to see what is actually happening. In my lab, we are developing tools that allow for the safer delivery of CRISPR for gene therapies, and I’m very excited about these technologies. CRISPR has benefits for clinical adult therapies, and beyond.”

Erika Camacho, an associate professor in the School of Mathematical and Natural Sciences at ASU's New College of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences, received the AAAS 2019 Mentor Award on Feb. 17 at the conference.

In addition, three ASU faculty — Bertram Jacobs, Hal Smith and Huan Li — also attended the 2019 AAAS Fellows ceremony in recognition of their career contributions to science, and were honored by other past ASU AAAS Fellows and colleagues. Jacobs and Smith were recognized for their pioneering efforts in biological sciences, while Liu was honored for his research in information, computing and communication.

Top photo: Emily Santora, undergraduate global health senior in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, and Barrett, The Honors College, prepares to give her poster session talk at the AAAS meeting.

More Science and technology

ASU receives 3 awards for research critical to national security

Three researchers in the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering at Arizona State University have received grant awards under the Defense Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research, or…

Celebrating 34 years of space discovery with NASA

This year, NASA's Hubble Space Telescope (HST) is celebrating its 34th anniversary of the world's first space-based optical telescope, which paved the scientific pathway for NASA's James Webb Space…

Making magic happen: Engineering and designing theme parks

The themed entertainment industry is widespread and diverse, encompassing everything from theme parks to aquariums, zoos, water parks, museums and more. The Theme Park Engineering and Design…