ASU adds Ukrainian to offerings of languages crucial to national security

Critical Languages Institute teaches immersive classes to accelerate proficiency

The Critical Languages Institute at Arizona State University has added Ukrainian to its roster of languages taught to bolster national security, and it’s one of the few immersive programs for that language in the United States.

Five students are taking beginning Ukrainian at the Tempe campus this summer in a seven-week course designed to accelerate competence in beginners. Besides the spoken language, they're also learning to read and write in the 33-letter Ukrainian version of the Cyrillic alphabet.

The U.S. government has designated Ukrainian as a critical language with proficient speakers in high demand, and the institute, part of the Melikian Center in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, teaches 11 of those languages. This summer, in addition to Ukrainian, the institute offers Albanian, Armenian, Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian, Hebrew, Indonesian, Persian, Polish, Russian, Turkish and Uzbek.

Geopolitics plays a role in why languages are deemed to be important. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Ukraine achieved independence, and after that, “A whole new generation is growing up speaking Ukrainian,” said Mark von Hagen, a professor of history and global studies who was interim director of the Melikian Center last year. He launched the program after securing donations to fund it.

Video by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

The institute’s courses are tuition-free, funded by federal agencies, partnerships and donors, though students pay an administrative fee and the cost of study abroad. The classes are open to anyone, including high school juniors and seniors. The federal Title 8 program pays for language instruction for graduate students, such as Brandon Urness, a student at the Thunderbird School of Global Management at ASU.

He became interested in Ukraine after hearing Sen. John McCain discuss the Russian invasion of Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula in 2014. Clashes between rebels and Russian forces in the region continue.

“Ukrainian is the most critical language in the world today with what’s happening in eastern Ukraine with the Russian annexation,” said Urness, who has a bachelor’s degree in political science. “That was the first time in my life I’ve seen something like that and it was shocking to me.”

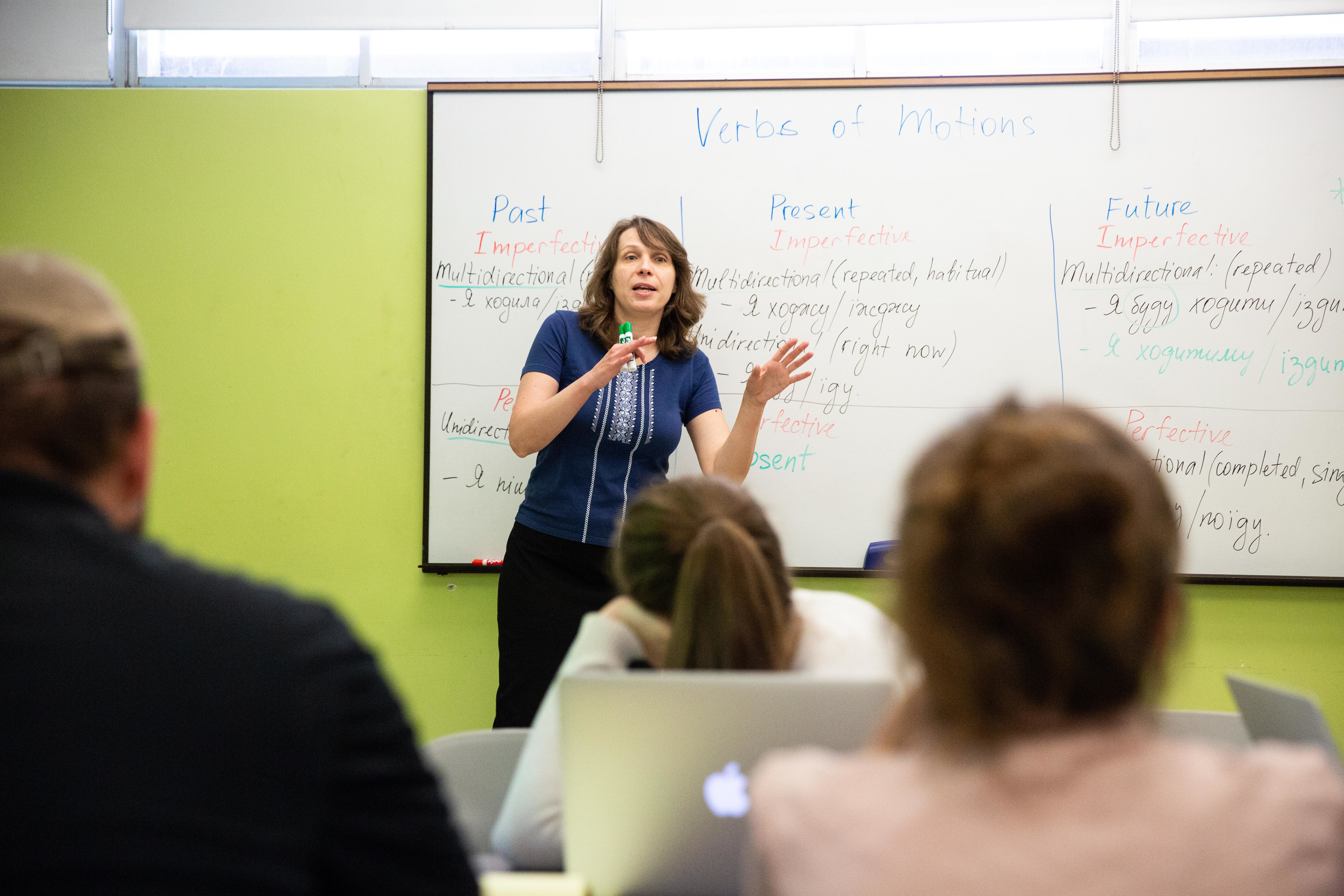

Professor Olena Sivachenko goes over motion verbs with her students during the Ukranian language course. The unique course is an intensive language course teaching the Cyrillic language and Ukranian to non-native speakers in a matter of weeks. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

Urness, who would like someday be an election observer in Ukraine, said the class is so intense that he’s been dreaming in Ukrainian every night.

“One of the biggest challenges is the amount of time it takes to master a language,” said Urness, who became fluent in Mongolian while serving on a mission there.

Jordan Tomlinson, a senior majoring in medical studies, is learning Ukrainian because he plans to attend medical school in Ukraine, where tuition is much cheaper.

“One of the hardest things about Ukrainian are verbs that differentiate between doing something once versus multiple times,” said Tomlinson, who’s also studied Russian. “Having to differentiate between the two is difficult.”

After the half day of class, the students spend many additional hours studying Ukrainian on their own.

“For me, it’s listening to music, watching videos and talking to my friends in Ukraine,” Tomlinson said.

“You just have to try to speak the language as much as you can.”

Ukrainian instructor Olena Sivachenko (left) assists students Olena Melnyk and Jordan Tomlinson in the Critical Languages Institute course. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

The immersive courses are not just for prospective diplomats, but also for people who study anthropology, history, literature, human rights and military policy, von Hagen said.

“A lot of people who are doing research in Russia are finding it more difficult because of restrictions on archives and interviews with officials, but many of us are aware that it’s easier to do the same work in Ukraine. They’ve declassified pretty much everything,” said von Hagen, who is teaching at the Ukrainian Free University in Germany this summer.

He said that the country is safe, except for the occupied area, which will likely have to adjust to being a “militarized democracy.”

“I teach Ukrainian history as an example of empires,” he said. “Russia was an empire and they’re still parting painfully with the past. All empires go down ugly.”

More Local, national and global affairs

Sustainability takes spotlight at ASU-hosted social work educators conference

The academic discipline of social work not only educates future social workers who help people cope with life’s challenges — it also advances research that furthers social change. To further that…

ASU at the heart of the state's revitalized microelectronics industry

Gradually, and then suddenly. It’s not only a famous line from Ernest Hemingway’s novel “The Sun Also Rises,” it’s an apt description of how Arizona has transitioned from an economy based on its…

ASU class connects students with veterans

A brand-new class offered this spring through Arizona State University's School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership is making an impact on students and military veterans. The course,…