Diamond electronics offer brilliant solutions

ASU professor exploring ways to use diamonds in electronics, cancer, space

Diamonds are among the most coveted objects in the world. As gemstones, they are brilliant, rare and symbolic. As a raw material, they are a physicist’s best friend.

If you think about certain characteristics of a material — hardness, for example, or ability to conduct heat — diamonds are usually at one extreme end of the spectrum.

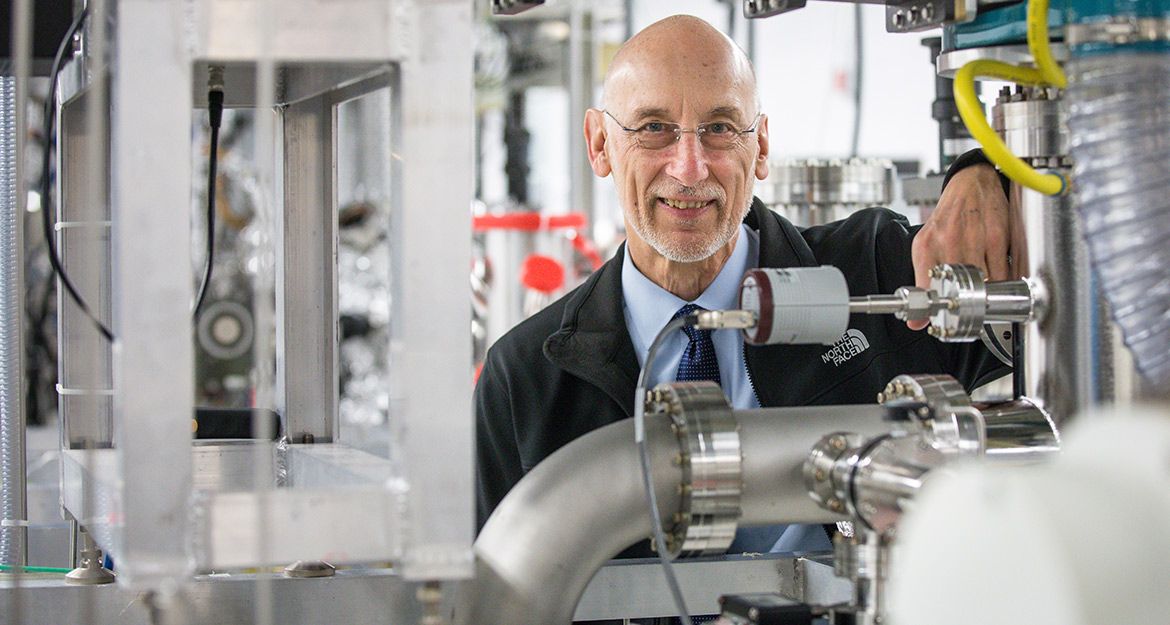

“It’s surprising that a material so simple, just carbon atoms arranged in this cubic crystal system, has such unusual properties in so many ways,” said Robert Nemanich, a Regents’ Professor of physicsThe Department of Physics is a unit of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. at Arizona State University.

As one of the world’s foremost experts on diamonds, Nemanich knows what they are capable of. And he has a different sort of proposal for how to use them.

Doping diamonds for better electronics

Diamonds are the overachievers of the materials world. They can sustain incredibly high temperatures and electric fields. They also conduct heat better than any other material. These properties make them ideal for very specific applications.

Currently, silicon dominates the electronics market. It’s used to make everything from your cellphone computer chip and laptop processor to microwave ovens. But as versatile as silicon is, there are certain areas where it falls flat.

“When it comes to high-temperature, high-power, radiation-hard devices, silicon doesn’t work as well. In fact, it doesn’t work at all,” said Manpuneet Kaur Benipal, a postdoctoral researcher in Nemanich’s lab.

Benipal and her colleague Brianna Eller both received their doctorates from ASU. With Nemanich as an adviser, they are now starting a company, ADVENT Diamond, to make electronic devices out of diamond.

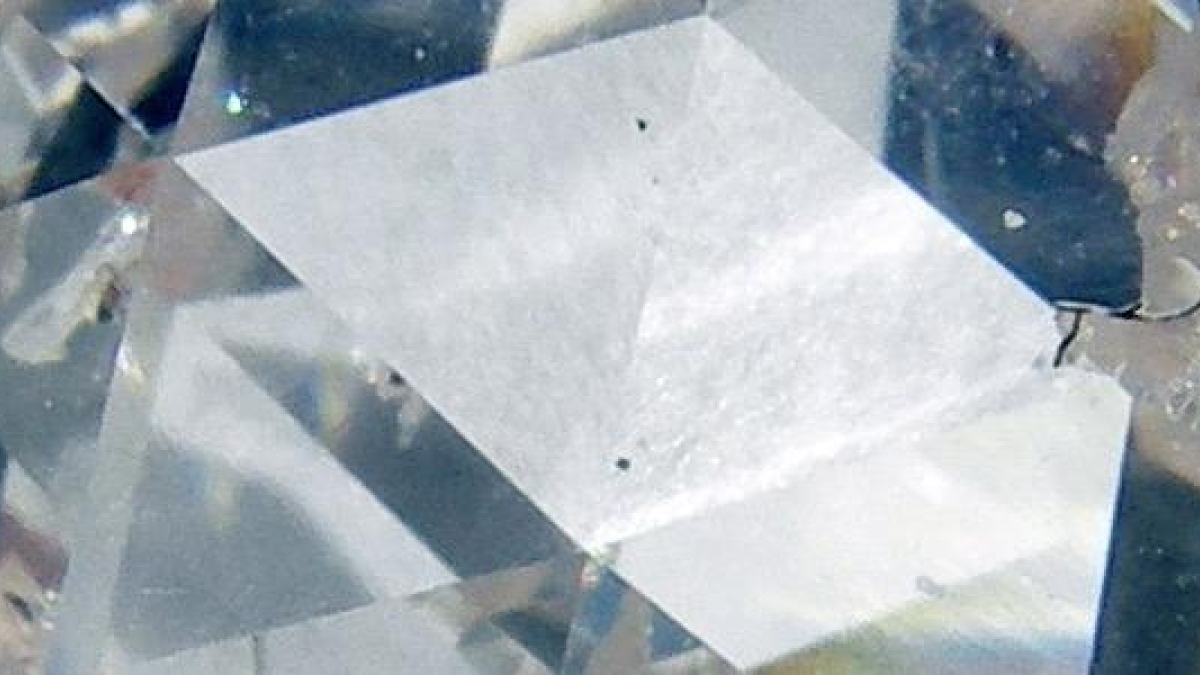

But we’re not talking about using recycled wedding rings. Eller and Benipal are working with doped diamond layers grown on small diamond plates. The ASU team even has a patent in the works for part of the growth process, called doping.

Take a tour of Robert Nemanich's lab and learn more about doping diamonds.

The term “doping” may conjure images of athletes illegally growing their muscles, but in the materials field, doping allows scientists to grow diamonds specifically for electronic purposes. Here’s how it works: You take a diamond substrate, or a small sample of diamond, and immerse it in a plasma composed of a mixture of chemicals. The atoms from the added chemicals organize themselves on the surface of the diamond, replicating the crystal structure of the substrate.

The lab-grown diamond layers that result include impurities that change the material’s electrical properties. Benipal and Eller use microfabrication processing of the doped diamond layers so that they behave precisely in the way they want. The process works so well that a small diamond can do the same work as materials that are much larger in size.

Does this mean we can expect to see tiny diamonds in our smartphones soon? Not exactly. Silicon continues to be more cost-effective for low-temperature applications, like cellphones and laptops. But diamond is a good choice for anything with a high-powered engine, such as an electric vehicle or an aircraft. Because diamond is excellent at conducting away heat, it would completely replace the need for a cooling system. Diamond also works well at very high pressures, which makes it perfect for deep-earth drilling.

More precise cancer treatment

We know diamonds’ ability to withstand extreme heat and pressure makes them superheroes in the world of electronic devices. But they have another power that scientists are harnessing to improve an entirely different field — cancer treatment.

Diamond is radiation-hard, meaning it takes much longer than most other materials to degrade under X-rays, gamma rays and fast charged particles. This property makes diamonds an ideal material to build radiation detectors for a variety of applications, including proton beam technology. This is a form of radiation therapy that precisely targets and destroys tumors with highly charged subatomic particles called protons.

Researchers at Nemanich’s lab, along with proton beam experts at Mayo Clinic Arizona, are working together to see if the use of diamond detectors can further enhance proton beam’s benefits to patients. Mayo Clinic is currently the only site in the Southwest to offer the technology.

Mayo Clinic’s intensity-modulated proton beam therapy features pencil beam scanning, which deposits streams of protons back and forth through a tumor. The beam closely targets the tumor, while largely sparing surrounding healthy tissue and organs from its radiation.

The researchers are studying to see if diamonds can be used as a detector for the pencil beam to go through. This could possibly help radiation oncologists further fine-tune the path of the protons, which could be particularly beneficial for pediatric patients.

“It’s most important in children to spare healthy tissues because those tissues are still growing, so we have to be very careful to treat as little of the healthy tissue as possible,” said Martin Bues, a proton beam physicist and researcher at Mayo Clinic’s Phoenix campus who is working with Nemanich and the ASU team on this project.

“It’s surprising that a material so simple, just carbon atoms arranged in this cubic crystal system, has such unusual properties in so many ways,” said Robert Nemanich, a Regents’ Professor of physics at Arizona State University. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

A diamond in the sky

If diamond is a material superhero, perhaps it’s only fitting that scientists want to send it into space. Nemanich was recently awarded a grant from NASA to build diamond electronics for a rover that will explore the surface of Venus.

“Venus is 450 degrees centigrade,” Nemanich said, “So it’s very, very hot.”

How hot, exactly? To give you an idea, 450 degrees centigrade is about 842 degrees Fahrenheit. In comparison, the hottest weather ever recorded on Earth was a mere 129 degrees F, in Death Valley, California, in 2013.

Through the NASA grant, Nemanich and his team are building an amplifier, a device that increases the power of an electrical signal. But Eller said that diamond could be useful for other parts of the rover as well, since very few other materials can function in such extreme heat.

As demand for high-powered electronics increases, diamonds will have an even larger role to play. Space exploration, electronic vehicles and deep-earth drilling only scratch the surface of potential applications.

Just as silicon brought about a new era of electronics, novel materials often drive the progress of new systems and devices. Perhaps the most exciting applications for diamonds are those that haven’t been thought of yet, since diamond would enable them to be built.

“There is always a need for something bigger, something better, something more efficient, something that works at higher temperature or higher voltage, which we think diamond can do,” Eller said.

More Science and technology

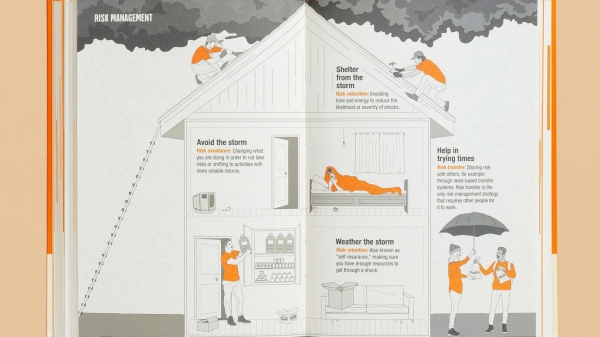

ASU author puts the fun in preparing for the apocalypse

The idea of an apocalypse was once only the stuff of science fiction — like in “Dawn of the Dead” or “I Am Legend.” However these days, amid escalating global conflicts and the prospect of a nuclear…

Meet student researchers solving real-world challenges

Developing sustainable solar energy solutions, deploying fungi to support soils affected by wildfire, making space education more accessible and using machine learning for semiconductor material…

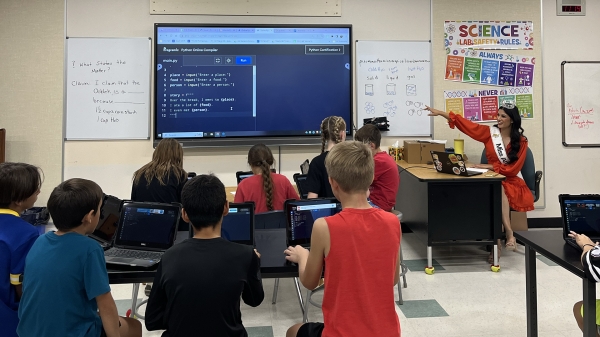

Miss Arizona, computer science major wants to inspire children to combine code and creativity

Editor’s note: This story is part of a series of profiles of notable spring 2024 graduates. “It’s bittersweet.” That’s how Tiffany Ticlo describes reaching this milestone. In May, she will graduate…