Searching for the first Sun Devil war heroes, part 3

Like Pat Tillman, Howard Draper and Albert Pitts died in combat; they were killed during WWI along the Western Front

Editor's note: This is the third in three-part series that came from the search through history for the first Sun Devil war heroes. Howard Draper and Albert Pitts were killed overseas during WWI. Today, we learn about their lives on the Western Front and the legacies they left behind.

About 1 million American troops poured into France in the summer of 1918. They were under Allied command, not American, and were used mainly to augment Allied forces.

They weren’t thrown on the lines immediately. They trained with British and French troops, far from the front. The guns could be heard 30 miles away. They were billeted closer and closer to the front as training progressed. This was to acclimate them to the din of artillery, which former Tempe Normal School student Albert Pitts memorably described as being so loud it was “no longer sound.”

(Think about that for a minute if you want to understand what the Western Front was like. “No longer sound.”)

After landing at Brest in February, Pitts trained and worked different jobs. He wrote home in early April: “For the past month I have been battalion clerk, which is much to my dislike, for, being in the army, I would rather be delivered from the narrow routine and burden of petty duties and be doing the common work and drilling of soldiers. I'm going to raise such potent objection to office work and execute so poorly the manual of the pen and keyboard that I'll probably get that which I earnestly long for. I made a great simpleton of myself when I let out the evil word about my office experience. I have been dabbling and fumbling at idiot’s work. There is some enervating, noxious, death-dealing influence to office work which crushes my soul, paralyzes my mind, robs me of purpose in life, makes sweet tasteless. Never again, you field desk, you Corona embryo typewriter, thou pen, thou ink — ”

He goes on for four more lines.

One wonders at the reaction of Pitts’ father, James, to a letter he received after the war. It’s the type of note a guy would write to his dead buddy’s parents, full of praise but devoid of what they did together on leave.

“Al was in very great demand at divisional headquarters to do clerical work and they tried very hard to have him transfer, but he wouldn't think of it,” wrote Cpl. J.J. Walsh. “He said to me, ‘Joe, I might be of much better service to my country doing clerical work, but they never hear a big gun,’ and he said, ‘I'm in the infantry and if I should change it would look as if I was afraid to fight.’ So there you are. Mr. Pitts. If that isn't red-blood stuff why I have never seen any. Us boys often remark of what good positions Al passed up to get killed.”

James Pitts surely smiled, and perhaps recalled whatever story he heard the day he came home to a charred kitchenIn 1910, when Albert Pitts was 17, he accidentally set the kitchen on fire when his parents were away. He lit an oil lamp without a glass chimney on it, and the flame set a kitchen towel ablaze. Neighbors watering their yard put the flames out. .

Spectacle and 'corned willie'

In late May 1918, Pitts’ regiment was assigned to the 32nd Division. It was reorganized into four battalions in April and sent to a 27-mile-long sector on the border of France and Belgium in Alsace. It was considered quiet, which meant no major combat activity, but aggressive patrols and raids went back and forth every day. This was Pitts’ first visit to the front. He marched there, carrying a full pack. When he reached the first trench, he was so exhausted he “didn’t feel the slightest thrill. Had been anticipating the excitement for weeks, but none was forthcoming.”

Pitts writes about night duty guarding the line, firing his first shot and coming under fire for the first time. (With 8 feet of dirt between him and the enemy, “it affords considerable excitement with very little danger.”)

He writes about not eating for 36 hours. “The kitchens couldn't keep pace with the infantry,” he said. This happened a lot. The rest of the Army was as green as the troops.

War was spectacle to Pitts.

“We have chased the Germans from one stronghold to another, merely by the superiority of our guns and explosives. You cannot imagine a spectacle so stupendous, magnificent, terrible and destructive as an American barrage. Physical hell then seems to assert itself; there is no longer daylight, only red fire; no longer sound, only crash and whang.”

He described another battle: “an amazing spectacle; the blasts of artillery, the put-put-put of machine guns, the crack of rifles, these physical and objective circumstances are stupendous enough to leave an impression for a life time. The mere magnitude of the thousands of shells fired, the tens of thousands of bullets that whistle through the air throw individual perspective out of its true proportion, and leave one quite unable to be surprised by smaller events.”

In late July the division pulled out of Alsace and traveled by train to Chateau-Thierry in the Marne. The night before Pitts was billeted in a barn. “I rustled up a few candles and read 'Lorna Doone.' I stole the book from the YMCA.”

In the morning they marched — cursing their packs again — to another town where they boarded troop trains.

“At noon we were given a piece of red horse,” he wrote of corned beef, known as red horse, corned willie, etc. “I worked a bugler, who was dishing it out, for two pieces and stole a third. When the hike was resumed, I nearly perished for lack of water. Alas, how I repented the corned willie.”

The Battle of Chateau-Thierry

Howard Draper, among a handful of Tempe Normal School students who enlisted a month after the U.S. declared war on Germany, may have come under fire in July. He served in Company C, 109th Infantry, 28th Division. The 28th was shelled before they were put on the front lines.

The division’s first action came 1918.

The Germans launched an offensive that became the Battle of Chateau-Thierry. Four companies from the 28th were attached to a French division on the front line, while the rest of the division took up second-line defense positions.

This is the story of the 28th Division at Chateau-Thierry, told by Bloody Bucket, a website dedicated to the unit:

“In the early hours of July 15, the German 36th Division crossed the Marne River and attacked the Allied front. When the adjacent French units fell back, L and M Companies were surrounded. Wave after wave of Germans attacked the Pennsylvanians. Despite the overwhelming odds, the two companies stubbornly held their position and inflicted heavy casualties. At 8 a.m., the remnants of L and M Companies withdrew and fought their way back to the front line of the 109th, five kilometers away. Of the 500 assigned officers and men only 150 remained. The brunt of the German offensive now fell on the 109th Infantry and the other units of the 28th Division. For three days, the 109th held its positions while under heavy attack. Fighting in ravines, woods and trenches, the doughboys fought like veterans. A German after-action report described the battle as ‘the most severe defeat of the war.’ For its staunch defense the 109th was nicknamed 'Men of Iron' and the 28th was later dubbed the ‘Iron Division.’”

Draper might not have been there. An exhaustive (and exhausting — it’s five volumes and 3,000 pages) history of the division by Colonel Edward Marin — "The Twenty-Eighth Division: Pennsylvania’s Guard in the World War" — quoted a survivor as saying many of the replacements for Company C were not from Pennsylvania. Draper may have been shipped in as a replacement after the battle.

In a strange twist, our Arizona boys may have walked right past each other during the war — twice. The first time came during the night of July 30: Pitts was part of a force moved up to relieve Draper’s division.

Campus life at war time

The 1917 yearbook didn’t feature photos of the sports teams. “Due to enlistment of so many of the star athletes, the Saguaro Staff was unable to secure pictures of various athletic groups.”

ASU was known as the Arizona Territorial Normal School from 1889-1896. It was later known as the Tempe Normal School during WWI.

Enrollment dropped drastically because of the war. In 1917, there were 418 students. In 1919, that number had fallen to 320. The school didn’t exceed 418 students again until 1923, said ASU archivist Robert Spindler.

“Before the war, this was still one of very few places of higher education that was available between Texas and California,” Spindler said. “And so there were many male students who came here in that period because it was the only place you could get higher education and qualify to go to somewhere like Stanford or the big colleges elsewhere. So, before the war, it wasn’t quite as female-dominated in student body. During the war, it was very likely it was dominated by females. That also had an impact on sports, because they were having trouble fielding teams for the male sports. Things like women’s basketball were very popular in that time.”

President A.J. Matthews didn’t forget the students who had gone overseas. University archives hold a list typed at his request of students in the American Expeditionary Force. Asterisks mark the casualties.

War gardens were planted on every available plot of ground. The Food Conservation Committee preserved and dried fruit, which was then sold to the dining hall. The proceeds were donated to the Red Cross. Salvage drives were held to bring in iron, tin, rubber, brass, copper and other materials. Matthews became the Tempe president of the National Red Cross. The campus chapter of the Junior Red Cross knitted hats and gloves for troops.

Looking back through editions of the Tempe Normal Student, the student newspaper, the war begins to bleed into campus life. Amongst the usual fare of recitals, house meetings, “hiking parties” and assembly notes, war-related news appears.

Across the Vesle

American infantry going into action west of Fismes, France. Both Arizona men in this series fought in Fismes. Photo courtesy of the American National Red Cross photograph collection (Library of Congress)

The Americans, led by the French, now faced driving the Germans north back across the Vesle River in France. They fought for days over fortified farms, fields and woods. Pitts went back into action on the morning of July 31. The 125th and 126th infantries were tasked with breaking the kaiser’s last line of resistance south of the Vesle.

In the week of countryside fighting, Pitts’ division captured 18 villages and fortified farms, four pieces of heavy artillery, five pieces of light artillery, 10 trench mortars, 28 machine guns and hundreds of rifles. One German officer and 96 soldiers were taken prisoner.

By Aug. 4, the Germans had been driven into a small town called Fismes on the Vesle. Both Arizona men fought in Fismes. The Germans fought back with the crown prince’s storm troopers, flame throwers and snipers. To give an idea of the battle’s ferocity, 90 percent of the town was destroyed.

In the first two days of the battle, Pitt’s 32nd Division lost 2,000 men.

Even after the Germans were driven out, snipers remained and the town wasn’t firmly in Allied control for a month.

Then our boys walked past each other a second time. On Aug. 7, the 32nd Division (Pitts) was relieved in the front at Fismes by the 28th Infantry Division (Draper). Draper and his comrades in the 28th began calling the Vesle Front “Death Valley.”

Sausages and corpse water

The Quentin Roosevelt plane crash. Photo courtesy of Theodore Roosevelt Digital Library/Dickinson State University

Pitts wrote home about this break from the line. The company was paid. Men bought bread, eggs and jam. Some went to mess. Most went into the woods and cooked their own food.

He and a friend went into town and “managed to have supper after a fashion with a German family. The old frau was very unfriendly, and was willing to feed us only after the display of a large number of francs. I bought a bottle of champagne, which probably played a good role in winning her over to our cause of eating. At the supper table were her two daughters, their fat-headed lovers, and one little girl about six or seven, who had big brown eyes. I gave her a few sous. All were sulky and morose; I very affable with my meager French; treated them all to a drink, and for a few slices of sausage and potato salad we parted with five francs.”

Pitts strolled through the village, bought some Swiss cheese and a can of apple jelly, and drank water from a clear babbling brook that reminded him of Tennyson.

“Only when I went up the stream fifty feet I found a dead Boche in it. Since that time I have been desperately ill. Affectionately, ALBERT.”

As a postscript, Pitts sent something he’d picked up. “The enclosed piece of canvas is not sent as a souvenir, but a suggestion of historic value. It is taken from the plane of Lieut. Quinten (sic) Roosevelt.”

On Aug. 7, soldiers from Pitts’ division found the grave of Lt. Quentin Roosevelt, son of former President Theodore Roosevelt. He had been shot down behind German lines on July 14.

The Germans buried him next to his wrecked plane where it had crashed and gave him a large funeral with military honors.

American troops found the grave and the wreckage of Roosevelt’s plane intact, except for the engine. Within about 24 hours the plane had been disassembled and carried off by souvenir hunters. Someone even pilfered Roosevelt’s dog tags, which the Germans had fastened to the rudimentary cross they erected to mark the grave.

Before the division moved on, soldiers from the engineer regiment made some improvements to the grave and a major general wrote a letter to Theodore Roosevelt to inform him that his son’s grave had been found.

Twenty days later, Pitts’ regiment was assigned to cross the Aisne River and relieve the French.

The exchange of troops happened the night of Aug. 27-28 at 2 a.m. This was going to be the second battle of the war for the 32nd Division.

It was Pitts’ last.

Battle of Juvigny

American Red Cross men distributing chocolate and tobacco to men coming from the first line but who were still being held in support near Juvigny, France, in September 1918. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress

The French general commanding the 10th French Army (of which Pitts’ 32nd Infantry Division was a part) ordered a general attack on the town of Juvigny on Aug. 29, with the objective of a complete break through the German line. Pitts went into battle alongside two tank companies and a troop of Moroccan cavalry. He surely would have mentioned both had he survived to write another picaresque letter.

A tremendous artillery preparation had been delivered during the night, followed by a rolling barrage in front of the attacking infantry in the morning, but the Germans were dug into caves and fortified machine gun nests. The 32nd soon found they occupied a bad position, on high open ground on the slope of a hill facing the enemy. There was little cover, except shell holes, and they faced artillery and machine gun fire from positions with excellent views of the Allied front. The position couldn’t be abandoned without endangering the French; as a result, the casualties were high. Shortly after noon, the Germans counterattacked. The American machine gunners held their ground and repelled the counterattack. Casualties were high on both sides.

A wounded friend of Pitts was in the hospital. A comrade came in who was next to Pitts at Juvigny when he was killed. Cpl. J.J. Walsh had been friends with Pitts since boot camp, and they fought together. It was Walsh who wrote to Pitts’ father after the war. He began with this sentence: “He was a mighty changed boy to what he was when I first met him.”

“The division was … sent to the Soisson front and that is where poor Al got hit,” Walsh wrote. “The boys were raiding some machine gun nests that were holding up the advance and as usual Al was among them. He was absolutely fearless and was continually volunteering for anything and everything that turned up. He and I have been through hell together, Mr. Pitts, and I was proud to know and have him for a pal. He was hit by a machine gun bullet and died instantly. Our company lost heavily at the time and today there is very few of the boys left that came over with us. Albert was loved by everyone in the company, both officers and men.”

Days later

Seven days after Pitts was killed, Draper was 27 miles east on the Vesle River at Magneux (98 miles northeast of Paris). Air observers noticed a general German retreat. Orders were given to pursue and attack.

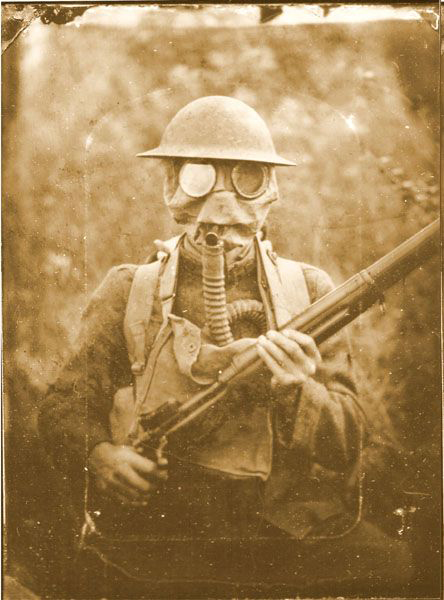

109th Infantry soldier wearing a gas mask.

Three battalions of Draper’s division, including his 109th Infantry, crossed the river in the afternoon of Sept. 4. The plan was for them to leapfrog over each other, advancing 5 miles to the Aisne River.

Col. Edward Marin described the situation in his exhaustive "The Twenty-Eighth Division: Pennsylvania’s Guard in the World War":

“After advancing about a mile from the river, through the woods which ran up the slope, they emerged into the open. Immediately it seemed as though the heights above the river were massed with machine guns and from their dominating position they could sweep the whole plateau. Patrols were sent out that night, and those that returned brought in the information that the enemy had strong machine gun positions across the entire front of the One Hundred Ninth.”

The commanding officer ordered an attack on the morning of Sept. 5. When the first battalion reached the top of the slope, German machine gunners mowed them down.

John Hanlon described the day in his book "A History of Pittsburgh and Western PA Troops in the War." He specifically mentioned Draper’s company:

“One of the American units which met real opposition at about this stage of the advance was the 109th infantry. … The 109th infantry covered itself with glory in the advance across the five miles of hill, valley and plateau between the Vesle and the Aisne. Company C of the 109th suffered heavy losses, and on the Aisne plateau this company displayed amazing morale and fighting ability and strength with tenacity of purpose, so characteristic of all the American fighters in the world war for freedom.”

The Germans kept a steady hail of bullets ripping across the open plateau into the night. Ration parties sent to the front were wiped out. Men were sent back to guide them by the least dangerous route, and all were killed.

Draper was killed either in the daylong assault or looking for food that night.

Beginning of the end

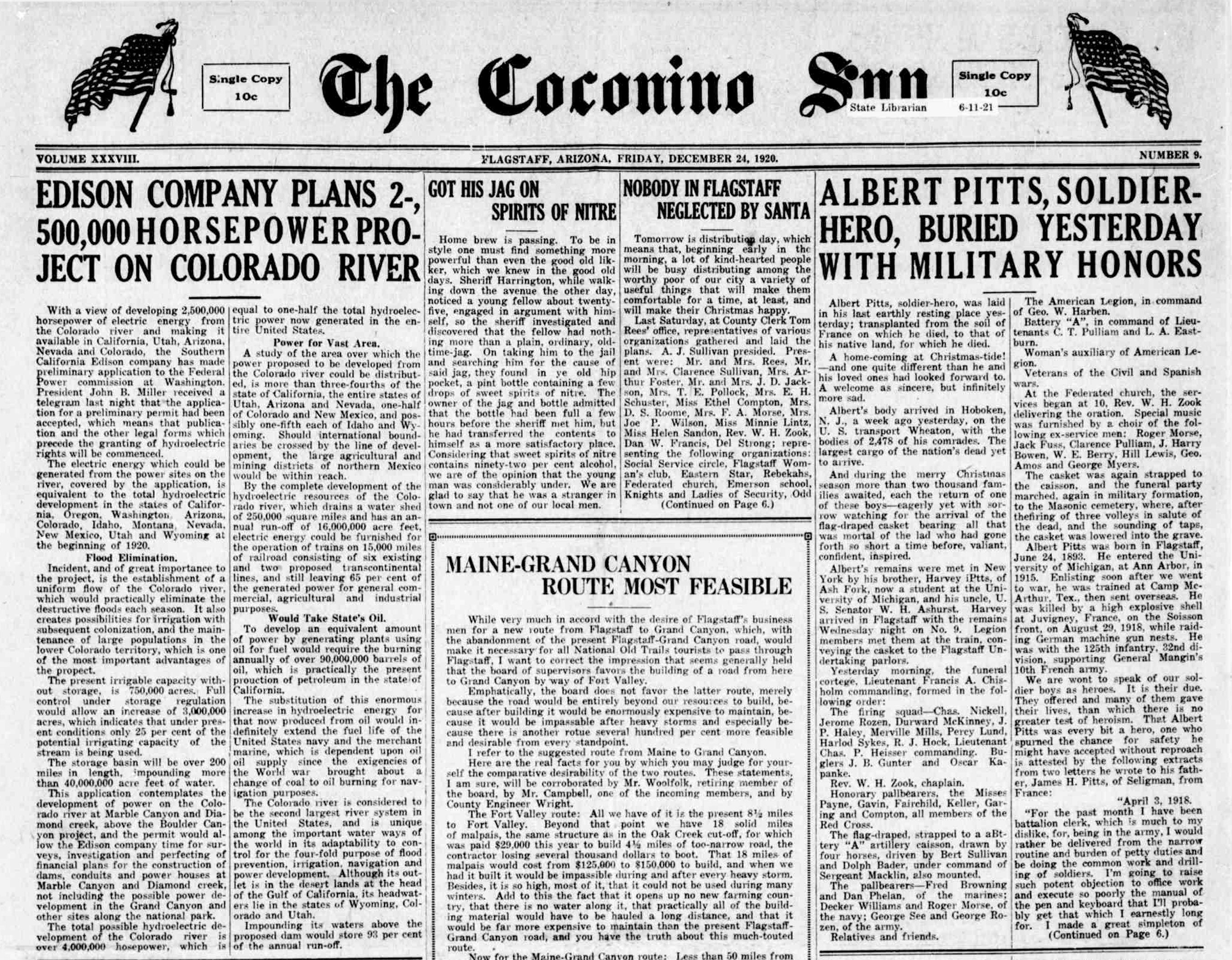

Flagstaff's local paper, The Coconino Sun, published a story about Albert Pitts' death and funeral. Pitts was born in Flagstaff in 1893.

On Sept. 7, 1918, the pursuit came to an end, and the Americans and French were on the Aisne River. Draper’s 28th Division was pulled off the line the same day. It suffered 8,772 casualties during the Aisne-Marne and Vesle River campaigns and 14,000 in the entire war. Pershing dubbed it the “Iron Division.”

Thus ended the Second Battle of the Marne. It was the beginning of a series of German defeats that would lead to the end of the war three and a half months later.

“A lot of it was because of Howard Draper and those men who were in very early; they proved themselves in battle,” said ASU historian Heidi Osselaer. “And when the Germans saw how effective they were that summer of 1918 … they performed very well, and it proved this was just the beginning; there’s millions of these boys in America and they’re just gonna keep coming, and they’re gonna keep coming.”

Fresh American troops arrived at the rate of 10,000 a day, when the Germans were unable to replace their losses.

“That was the period where it was guys like Draper that went in early and gave their lives, but they fought well, and all their leadership performed well, and there was equipment coming,” she said. “That was the big thing that was gone for the Brits and the rest of the Allies, so I think this was a turning point.”

Return home and legacy

On Oct. 19, 1918, the Arizona Republic published a casualty list. Draper is listed as a private. (He was most likely posthumously promoted to corporal, according to Sgt. Damian J. M. Smith, command historian, Pennsylvania National Guard.)

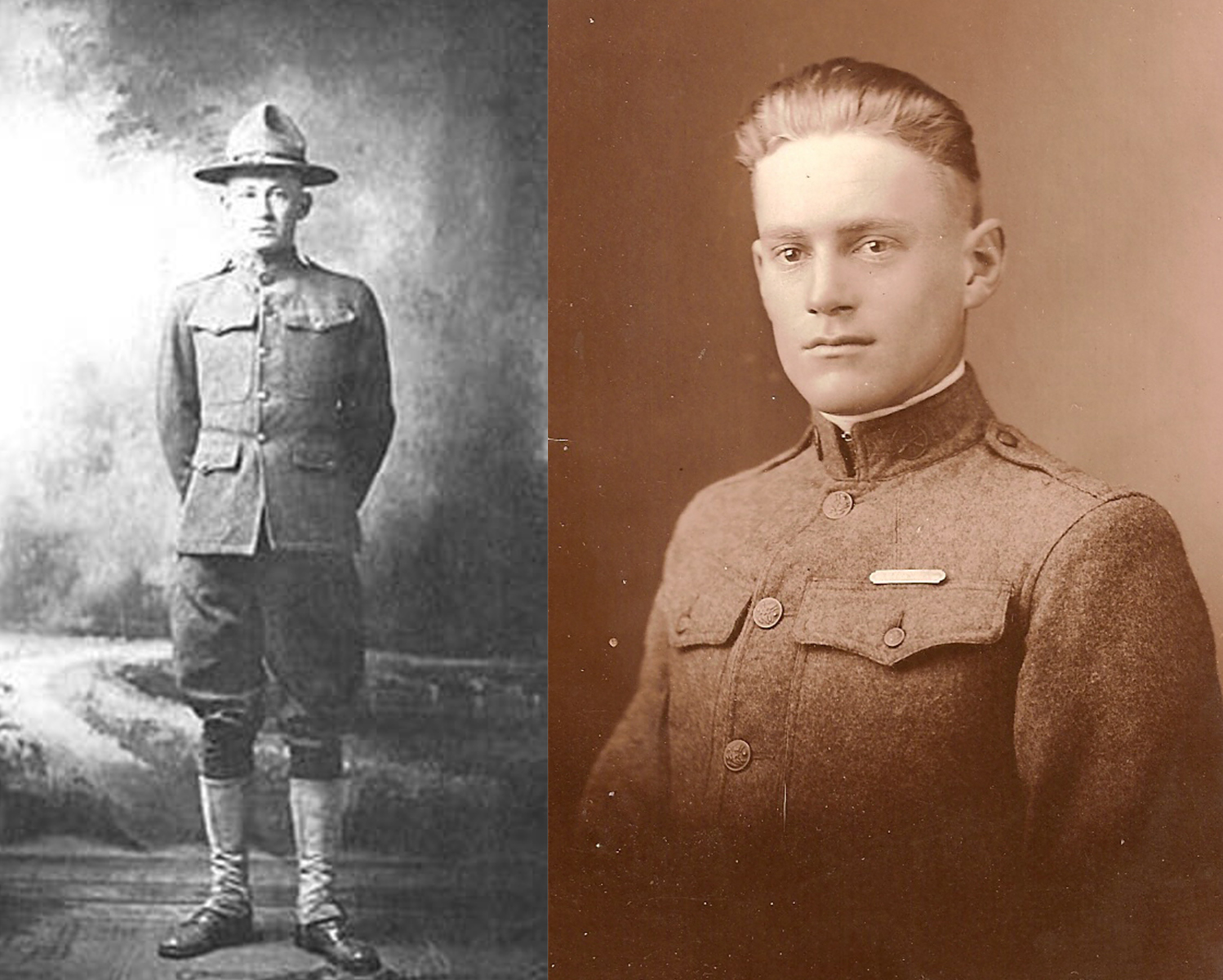

Albert Pitts (left) and Howard Draper. Photos courtesy Arizona State University

On Oct. 23, 1918, The Weekly Journal-Miner of Prescott reported Albert and Martha Draper had received a telegram from Washington. The Drapers were living in a mining camp in a town called Constellation, southeast of Crown King. Constellation is a ghost town now.

“Another Yavapai youth has fallen in France,” the paper reported. “This young man was in every sense a patriot, and his sincere desire to help win the war was shown when he manfully stepped forward and went into the ranks.”

Meanwhile, Pitts was the first former Arizona state employee killed in action. His body arrived in Hoboken, New Jersey, in December 1920 on the U. S. transport Wheaton, along with the remains of 2,478 of his comrades. It was the largest cargo of the nation's dead yet to arrive from Europe.

His brother Harvey escorted his remains back to Flagstaff from New Jersey. He was buried a month later in the Citizen Cemetery.

Draper’s body wasn’t shipped home until three years later, in June 1921. By this time his parents were living at the White Mine outside Wickenburg. His remains were sent with two other Arizona men by train from Hoboken, New Jersey, to El Paso. Wreaths on their coffins were inscribed, “With sympathy and pride Arizona pays homage to her soldier dead.”

Draper was buried in Mountain View Cemetery in Prescott, alongside governors, congressmen and Indian fighters. The cemetery lists six famous people interred on the grounds. Draper’s name is not among them. A small stone set into the ground marks his place: “Howard M. Draper, Arizona, Cpl. 109 Inf. 28 Div., September 5, 1918.”

That was his physical end. In Arizona, he stayed far from forgotten.

Draper had an impact on his history professor from Tempe Normal School. John Murdock was dean of the school from 1933 to 1937. He was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives and served from 1937 to 1953.

Remarks he made in Congress on Nov. 10, 1941 (the day before Armistice Day) were reprinted in the Casa Grande Dispatch 18 days later. America was in an isolationist mood once again (though only for a few more days, until Dec. 7). The consensus was that getting involved in World War I had been a mistake.

“I shall think of some young men, former students of mine in the year 1917. I might mention one, Howard Draper of Wickenburg, Ariz. He studied government with me in the spring of 1917.”

Murdock quoted from an essay referenced by the Republic in its 1933 remembrance of Draper and Frank Luke.

“He and four others volunteered within a few days, and Howard lost his life. I am thinking of his mother, and America’s whole effort then was a mistake. Such is not the verdict of history.”

Eighty-four Sun Devils have been killed in combat.

Searching for Sun Devil war heroes

Part 1: Pitts and Draper: Different, yet similar

Part 2: An unpopular choice to enlist

Part 3: Life — and death — at the front

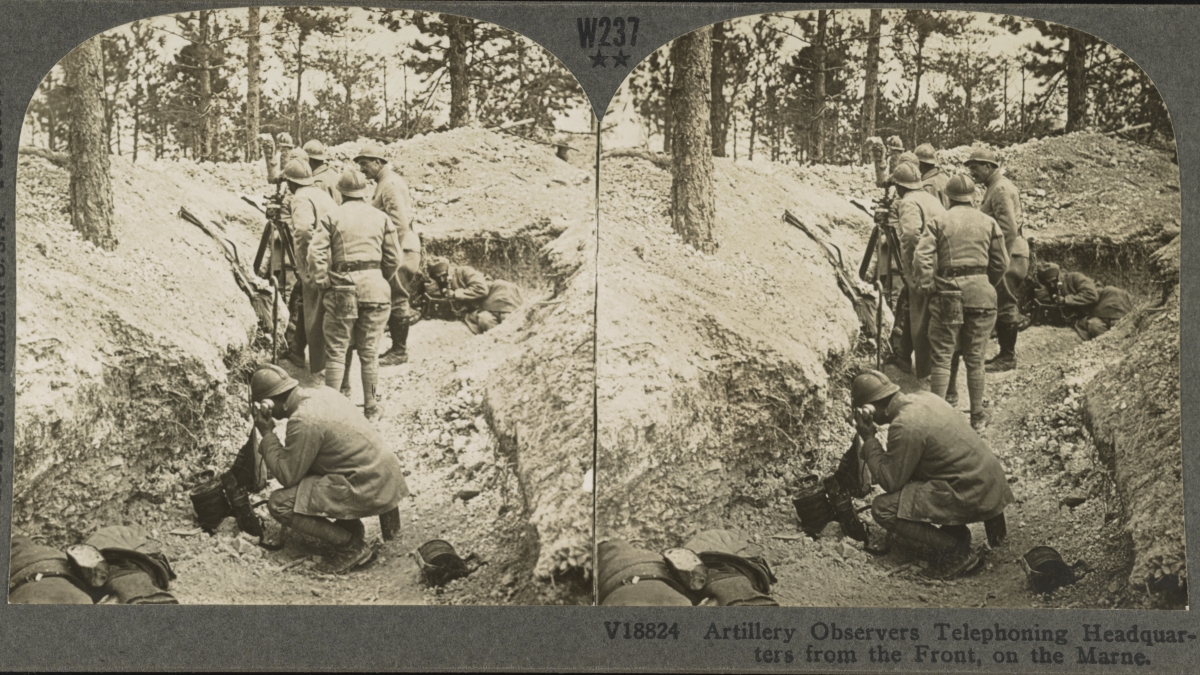

Top photo: Artillery observers telephone headquarters from the front, on the Marne in France. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress

More Law, journalism and politics

CBS News president to give keynote address at Cronkite School’s spring convocation

Ingrid Ciprián-Matthews, president of CBS News, will serve as the keynote speaker at Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication spring 2024 convocation. …

School of Politics and Global Studies director's new book explores mass violence

Why do people commit atrocities and why are certain groups, including religious and ethnic, more vulnerable to large-scale violence? These questions are explored in a new book by Güneş Murat Tezcür…

ASU faculty contributing to improvement of Wikipedia

Many academics have a love-hate relationship with Wikipedia. While the website has information about almost anything you can imagine, the credibility of that information is sometimes suspect. Tracy…