She Se Puede: ASU alum creates opportunities for Latina girls in STEM

Si Se Puede Foundation has been organizing robotics programs for East Valley students for nearly 20 years

Update: The Degrees of Freedom team won the Rookie All Star Award at this weekend's FIRSTFor Inspiration and Recognition of Science and Technology Arizona West Regional 2017 and advance to the FIRST Championship competition in Houston during the weekend of April 22.

A team of high school girls is ready to compete in a robotics competition Saturday in Phoenix thanks to a nonprofit organization founded more than 20 years ago by Arizona State University alumnus Alberto Esparza.

The Si Se Puede Foundation focuses on helping children from low-income families achieve academic success, but they’ll take anyone who wants to join their robotics programs. Esparza said that since 1998, his program has seen about 85 students go on to become engineers.

The group’s work highlights a range of outreach efforts from the ASU community that include Camp Catanese, a tech-heavy college access program for Phoenix students; CompuGirls, a STEM program for minority girls; Conexiones, an academic achievement program for children of migrant workers across Arizona; and the Upward Bound Project, a college prep program serving potential first-generation college students.

The Si Se Puede Foundation’s newest team, Degrees of Freedom, a collection of predominantly Latina East Valley girls, wants to start gathering trophies. This is their story:

–––

It’s spring break and a chilly, dark morning as seven young girls huddle together for a selfie in the Chandler Techshop parking lot.

The Degrees of Freedom high school robotics team is headed to Flagstaff for the FIRST regional robotics competition where they hope to claim the rookie all-star award for first time teams. Alberto Esparza, CEO of Si Se Puede that funds the team, checks everyone is present and snacks are accounted for as they get ready to leave at 5 a.m..

Outside the parents of Valeria and Camila Treviño huddle together as they see both their daughters off. They would go, but they can’t afford to spend time away from their jobs. As the vehicle begins to drive off, Valeria and Camila’s mother walks alongside as she waves goodbye.

–––

Alberto Esparza, with his graying hair and trimmed mustache, towers over children running through the Hartford Elementary cafeteria. Little ones tug at his shirt to show him their Lego robots or run into him for a quick hug. Esparza walks with a gait of authority that would have served him well 23 years ago as a probations and parole officer.

Thinking back to his undergraduate years, Esparza comments, “when I was at Arizona State University, I saw myself going into the FBI; I saw myself becoming an attorney. But I had a passion for the community.”

In 1993, Esparza felt he had reached a crossroads. He left corrections, and a lucrative position, to spend his life savings on creating the Si Se Puede Foundation with no previous non-profit experience and little support from his family — who couldn’t understand why he left a stable career path.

Esparza became the primary teacher of foklorico dance groups, soccer programs and even ESLEnglish as a Second Language classes with the hopes of improving the odds of succeeding in high school and college for the children of his East Valley community. Working in corrections had made him feel he was treating problems rather than preventing them. “It’s not that I’m a tough guy,” he said of his own success in school, “I grew up in that environment, too.”

After four years of work, Esparza found himself broke and sleeping in his unheated office on a cold November night questioning his choices. But that same year Si Se Puede received its first funding grant from United Way for $25,000.

“I don’t mind saying that the application that I filled out was filled out in pencil. I didn’t have a computer, typewriter, if you will, and I felt so uncomfortable when I submitted it.”

With the support of the Chandler Police Department and those who were familiar with his approach he secured the grant that allowed him to start Lego robotics programs in Chandler schools.

“I decided, ‘why don’t I bring robotics to the East Valley to communities deemed at risk,” Esparza said. “Your zip code shouldn’t dictate whether or not these programs are available.”

Today, Esparza’s Si Se Puede foundation partners with schools all over the Valley offering programs for a range of ages. His only rule is that they don’t charge students for participation. He has seen 85 students go on to study engineering at a variety of different universities and considers everything “his kids” go on to do a success.

As a young mother arrives at Hartford elementary and hugs her son, he points out she was once one of his students in elementary school. He remarks that this East Valley community is where his heart is and that his success may be impressive but a result of years of effort, “I’m not the smartest guy in the world, but I’m persistent.”

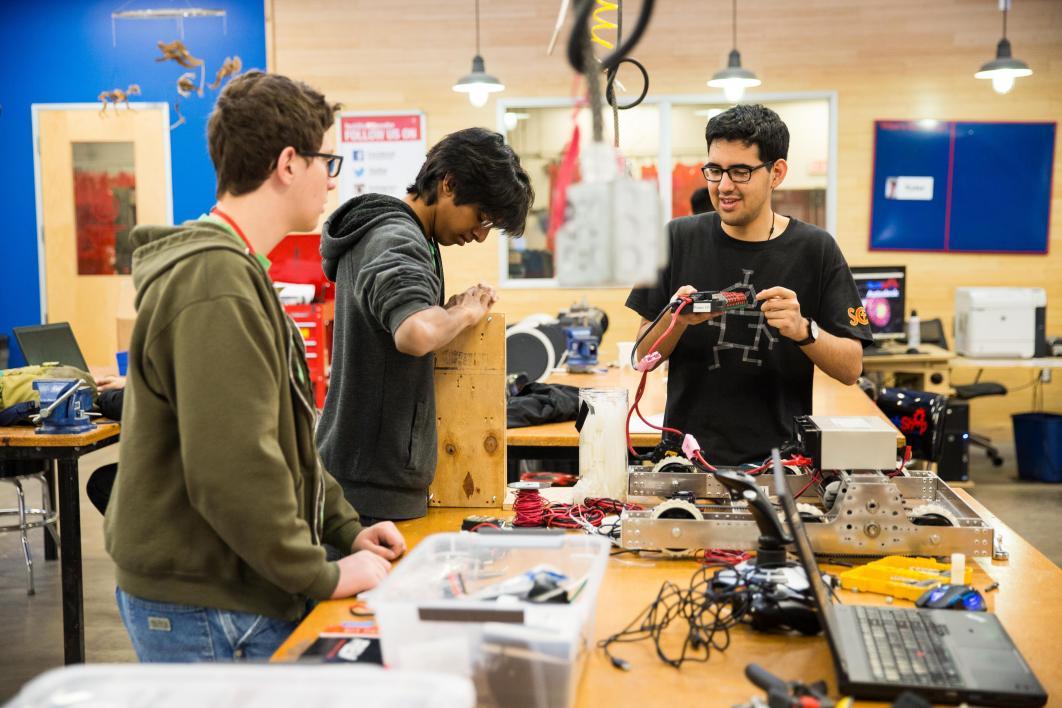

Before heading to Flagstaff for the FIRST robotics competition, the girls of Degrees of Freedom and the Binary Bots team, a co-ed team sponsored by Si Se Puede, spent every Saturday and sometimes weekday afternoons planning and building their team robots. Students from all over the Valley that participate in either team met at the ASU Chandler Innovation Center, which adjoins the Chandler TechShop. The teams must raise $5,000 to compete and money to purchase tools and equipment. The students work with mentors from General Motors, ASU alumni and ASU students to raise money and build robots.

The theme of this year’s competition is “STEAMWorks.” Robots must pick up gears and balls and then climb a rope.

ASU junior Ruy Garcia Acosta, who is now a mechanical engineering student, went through the program himself in elementary school and mentors students on both teams. He credited his time with Si Se Puede for opening up his perspectives.

“It helped be more intrigued about the engineering aspects,” he said speaking of his time in the program. Acosta manages to squeeze in time with high school students because, “I interact with the kids because they’re really smart and really bright, and I really like to make sure that they know that they’re on the right track.”

Acosta and other mentors supervise students and provide insight as they design their robots and use the equipment to cut, drill and program.

ASU alumnus Allan Cameron, a doctorate in elementary education, coaches the Degrees of Freedom team. He was part of the squad that beat MIT in a robotics competition that later was dramatized in the 2015 movie “Spare Parts.”

He met Alberto Esparza a few years ago at a party.

“He was thinking of starting a high school level team for the community,” Cameron said. “So there I am with a little drink in my hand, and I say if there’s anything I can do to help let me know. The next thing I know I’m spending five days a week working with the kids.”

"Dr. Cameron," as the kids call him, helped Esparza start the Degrees of Freedom this academic year, purposefully making an all-girls team to create more leadership opportunities. Cameron, who has daughters of his own, sees the team as an attempt to address larger cultural influences that deter many young women from STEM fields.

“Girls tend to get the Barbies. Guys tend to get the trucks, the dynamic stuff that moves,” Cameron said. “In here, they get to get dirty and break things … and culturally, we’re swimming upstream.”

Valeria Treviño is one of those young women on the Degrees of Freedom team and sees aerospace engineering in her future. Bailee Kagen is interested in quantum physics.

Treviño and her sister on the team joined Si Se Puede in third grade and have participated in every robotics program offered. The girls are able to come afterschool because their mother drives them every day and even gives rides to other team members. Treviño’s parents wholeheartedly support their daughters, who will likely be the first in the family to attend university. “My mom wanted to give us opportunities she didn’t have,” Treviño said.

With a month left to go before competition time, the girls are testing, driving and adjusting pieces of the robot frame. “Let yourself get comfortable, and make sure you have it where you want it,” a mentor tells the girls. They take turns drilling a hole into a piece of rectangular metal that is part of the robot’s adjusted frame.

Madeline Badger was using the drill as her teammates cheered her on. When she finished she exclaimed “nailed it guys!” Valeria Treviño, however, laughed, “You didn’t nail it, cause you’re not using nails.”

–––

The FIRST regional robotics competitions began in Flagstaff last month. Robots are weighed and measured to comply with competition standards. Teams are given the day to test their robots on the field or make adjustments before competition. The following day with music blasting and teams wearing matching red Mohawks and gold lame capes — there’s even a fully suited horse mascot — competition begins.

Months of labor are boiled down to a series of 2-minute rounds. As students compete, they collect points that give them their standing.

“I’ve had the time of my life,” blasts on overhead speakers the girls lip sync and goof off around the robot as they wait to compete in their first match.

Degress of Freedom drivers, Valeria Treviño and Madeline Badger, do their team handshake before heading to the driving port. The first 30 seconds, robots function automatically and as a buzzer sounds Valeria and Madeline dart out for their controllers. They maneuver their robot around collecting gears and in the last 20 seconds push their robot to climb.

As the competition wears on, the team continues to perform. But their final two rounds are plagued with communication problems from the controllers and a loose piece of hardware that prevents the robots from climbing.

As winners are announced, the girls have their hearts set on the rookie team award, given to the strongest community influence in their first year as competitors. It allows the winner to advance to international competition.

At the end of the day, different categories are called, the girls place seventh out of more than 50 teams. But they tear up as the final winners are announced and they don’t hear their names.

Esparza reminds them how highly they placed for a first-time squad while Cameron reminds them of a lesson he reiterates often, “You’re here to fail, because if you’re not failing, you’re not pushing hard enough; you’re just doing all the stuff that everyone has done before.”

At the end of the night, the girls shake hands and congratulate other teams. As Esparza prepares to leave the auditorium, the girls come bounding across the floor smiling and laughing. They’re teasing a teammate for getting her first kiss, on the cheek, from a boy on a competing team.

“It was in front of everybody, and everybody was like ‘beso, beso, beso,’” said Valeria Treviño as her teammate hides her face in her hands.

Later, over a dinner of chow mein and stir fry, they discuss strategy of how to improve their chances at the next regionals at Grand Canyon University.

Sights, sounds and efforts of competition.

More Science and technology

AI-equipped feeders allow ASU Online students to study bird behavior remotely

ASU Online students are participating in a research opportunity that's for the birds — literally. Online Bird Buddies is a project that allows students to observe birds remotely, using bird feeders…

National Humanities Center renews partnership with Lincoln Center for responsible AI research

The National Humanities Center has announced that Arizona State University's Lincoln Center for Applied Ethics is one of four organizations to receive funding for the second phase of their…

Advanced packaging the next big thing in semiconductors — and no, we're not talking about boxes

Microchips are hot. The tiny bits of silicon are integral to 21st-century life because they power the smartphones we rely on, the cars we drive and the advanced weaponry that is the backbone of…