Stronger together: When design and art meet science and technology

Herberger Institute artists, students work with scientists and big data in multidisciplinary projects

Microscopy. Big data. Seismology.

These are just some of the tools faculty and students at ASU’s Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts are using in their research and their work — work that also gives back to technology, science and other disciplines outside of design and the arts.

“The multidisciplinary environment of ASU and the energy and curiosity of the Herberger Institute faculty have fused to create this incredibly rich environment for the intersection of the arts and sciences — and beyond,” said Jake Pinholster, associate dean at the Herberger Institute. “We are rapidly moving to a place where design, the arts, the sciences, engineering and the humanities are drawing from one another to solve big problems and find new areas for exploration.”

Susan Beiner, Joan R. LincolnThe professorship was endowed in 2010 by David and Joan Lincoln, longtime supporters of a number of ASU programs ranging from Lincoln Center for Applied Ethics and the Center for the Study of Religion and Conflict, to those within the arts, law and ASU libraries. Endowed Professor in Ceramics, is teaching a new Arts and Science course in the ASU School of Art this semester.

“The art and science collaboration is an opportunity for art students to become exposed to areas of science to spark new concepts for their art as well as to open their mind to utilizing new techniques and materials,” Beiner said.

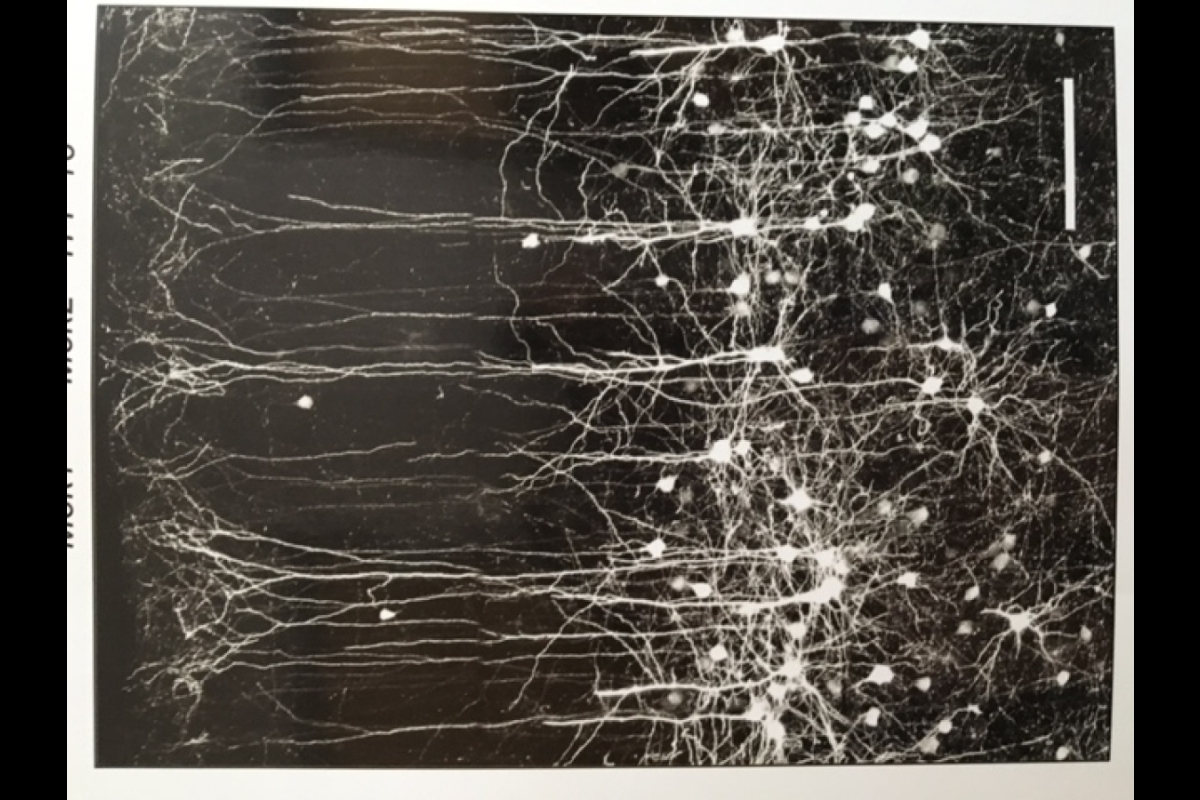

In 2015, the Herberger Institute’s School of Art partnered with the ASU School of Life Sciences (SOLS) for Sculpting Science, a project where art students worked with faculty in the SOLS Electron Microscopy lab to create works of art that represented electron microscopy images of various materials, from plant parts and pollen to sludge and fired clay pieces. The artists received inspiration for their art, and the scientists saw new ways of presenting their information and communicating their work.

“It was so successful that I decided it needed to be a class,” Beiner said.

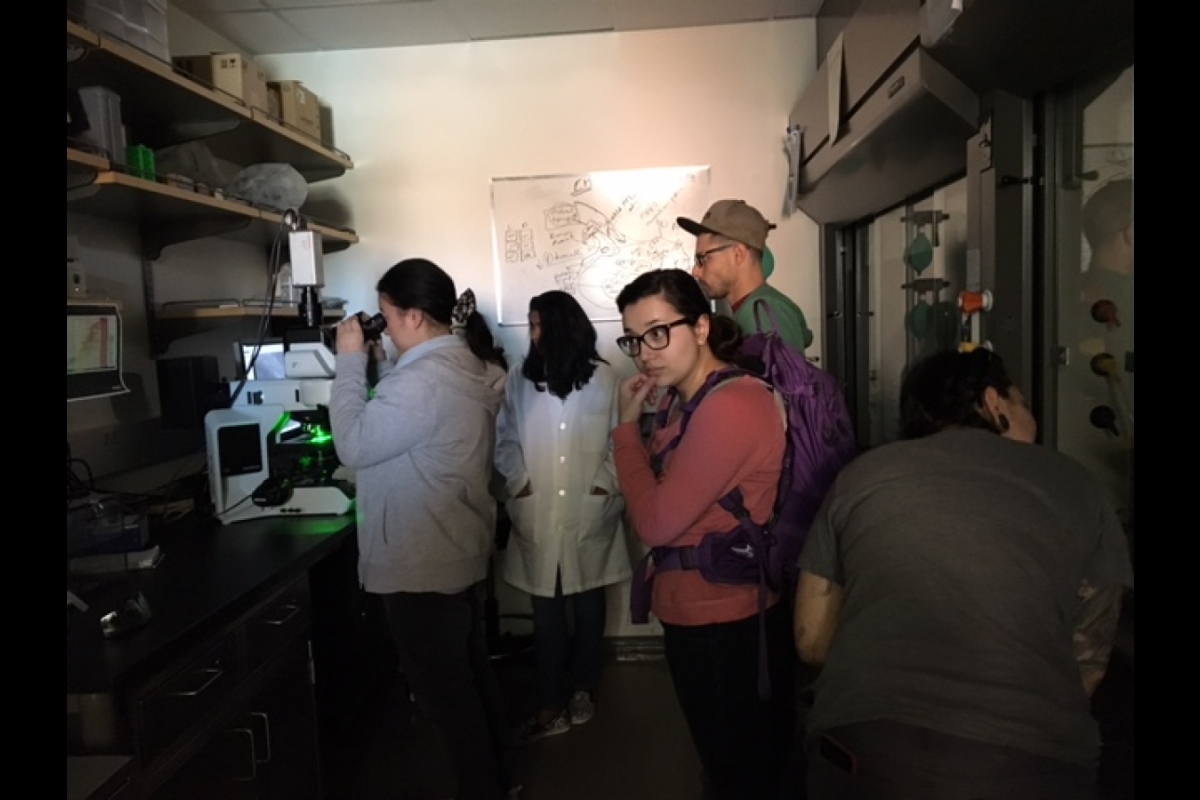

The new Art 494/598 course expands on the collaboration with Robert Roberson, associate professor in the School of Life Sciences, and using scanning electron microscopy scans. Students visit multiple labs and research collections in the School of Life Sciences and hear professors present their areas of research.

“In this ongoing relationship, the art students will translate new scientific hypotheses into visual imagery,” Beiner said, “and the scientists will gain rare insight into what their research could look like as real 2-D or 3-D objects.”

Roberson said he’s excited to continue working with the School of Art.

“Collaborations between scientists and artists can result in a beautiful piece of art for the artist and a means of communicating for the scientist: a win-win situation,” he said.

In the same way that Beiner’s students translated scientific scans from the Electron Microscopy lab into sculpture, Jessica Rajko uses dance to present big data beyond its purely technical aspect.

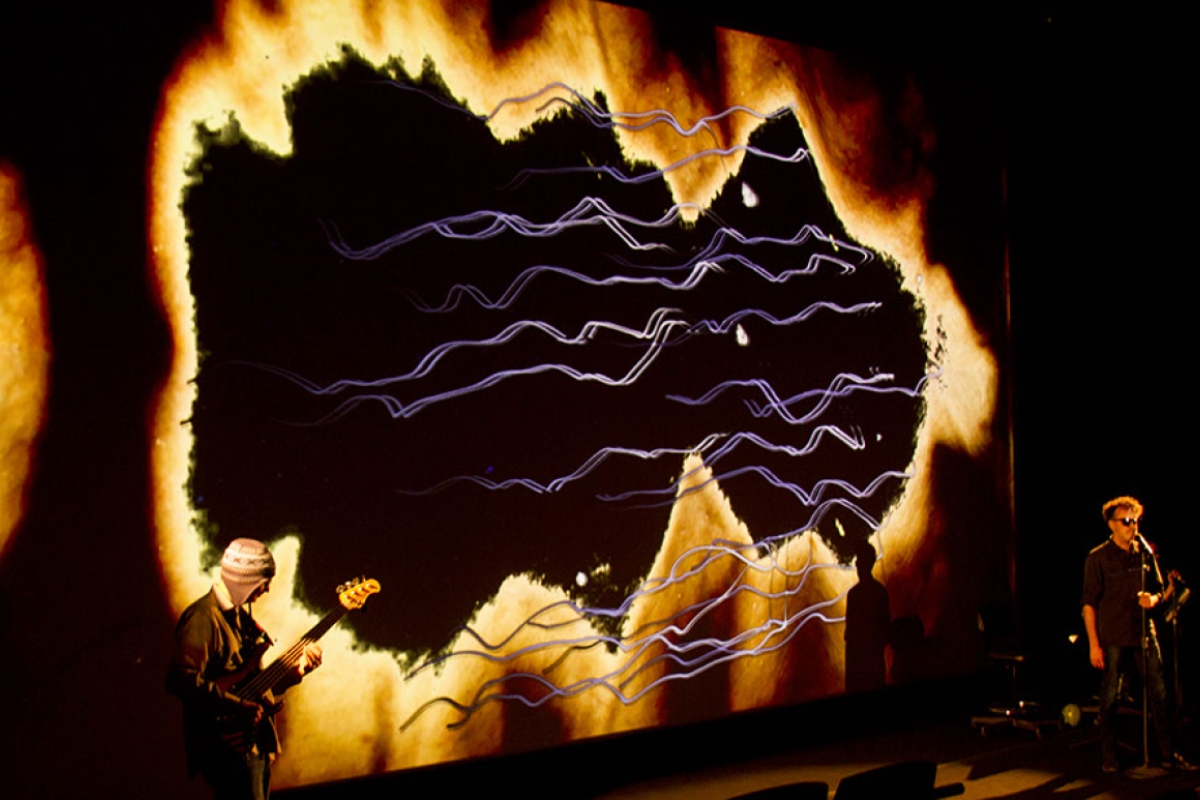

Big data is full of numbers and databases, charts and graphs, terabytes and gigabytes. But when Rajko, an assistant professor in the ASU School of Film, Dance and Theatre, looks at big data, she sees art. Her latest work, “Me, My Quantified Self, and I,” which premiered Feb. 10 at Unexpected Art Gallery in Phoenix, is the culmination of the past two years she spent researching big data.

“I was interested in how we make data tangible so that we can start to build meaningful tangible metaphors about humans’ relationship to data,” Rajko said.

Rajko’s research started with a project called “Vibrant Lives,” funded through seed grants from the Herberger Institute and the ASU Institute for Humanities Research. Rajko and her collaborators built interactive installations where people could feel their own data. In one installation, guests plugged their mobile phones into wearable devices that provided haptic feedback when they scrolled through their information, so they could feel how much data they were using.

“We were really interested in human experience of data,” Rajko said. “In this research we realized more and more how much people are implicated in big data infrastructures, because really big data is about people. It’s about human activity.”

One way her piece aims to make data feel less elusive is with the example of a giant 20- by 20-foot hand-crocheted net. Through a grant from the city of Tempe, Rajko enlisted the Tempe Needlewielders, a volunteer organization that creates and donates handmade items to local charities, to crochet objects onto the net during the performance.

“I really wanted to think about metaphors for data that more accurately reflect what data feels and looks like, which is messy and improvised,” Rajko said. “Having these women crocheting and building and growing this net live through the performance harnessed a lot of what I see as the behaviors of data.”

By creating these new metaphors and exploring the everyday experience with data, she’s reframing big data, both for a new audience and for those inside the bubble.

“Technology always feels like an insider’s game — we often feel like you have to be a computer scientist to understand,” Rajko said. “The arts in this particular case offer a different type of dialogue around technology, one that feels like it doesn’t talk at people but includes them in it.”

To expand that dialogue, when her show premiered the weekend included a facilitated group discussion about digital human rights, privacy concerns and decolonizing approaches to data use as well as personal cyber-consultations on protecting your data with ASU’s Global Security Initiative.

Lance Gharavi, assistant director of theatre in the School of Film, Dance and Theatre, also uses art to reach a wider audience. In May, Gharavi will present an hourlong performance piece all about the Earth’s core, called “Beneath.” In the vein of Radiolab or Cosmos, the show is a family-friendly scientific exploration of the Earth’s deep interior.

“People will hopefully leave understanding things about the science of the Earth’s material that they didn’t know before, and they will have had a great time,” Gharavi said. “We all gaze up into the sky and into the stars and wonder about what’s up there. We know the mass of Jupiter’s moons. We know what the atmosphere of Venus is made of. We know what the center of galaxy smells like; seriously, we do. But we know almost nothing about the what’s a few hundred miles underneath our feet. ... That’s what the show is about — that mystery of what lies beneath.”

Gharavi, who is working with geophysists, seismologists, mineral physicists, geochemists and other scientists at ASU, said he loves telling stories and loves working with scientists to tell their stories — stories about what they’re doing, what they’re learning and what they’re discovering.

“The advantage to the scientists is their work gets communicated to populations they might not have reached otherwise, and that’s in the case of this kind of work that I’m doing here, which is really about communicating science in a sort of discursive way,” he said.

The performance is part of a larger collaboration between the Herberger Institute’s School of Film, Dance and Theatre and the School of Earth and Space Exploration. Ian Shelanskey, a graduate student in the Herberger Institute studying interdisciplinary digital media and performance, is working with professor Edward Garnero and graduate student Hongyu Lai, both in the School of Earth and Space Exploration, to create a tomography visualization tool.

As Gharavi describes it, seismic tomography is basically taking a CT scan of the planet. The data output is columns of numbers. This new tool creates a picture of the Earth’s interior based on mathematical operations of the data. Scientists can use the tool to adjust the math and see changes in the picture in real time, allowing for deeper analysis and conversation.

Gharavi said this kind of interdisciplinary work is beneficial to everyone.

“The scientists and the designers and the artists that I work with all have different sets of training and skills and specialized knowledges,” he said. “Those are different among us, but we all have a passion for asking questions and finding answers and solving problems, and that’s what we do.”

Top photo: Jessica Rajko’s “Me, My Quantified Self, and I” dance work features a 20- by 20-foot hand-crocheted net as a metaphor for big data. Photo by Tim Trumble/Courtesy of the Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts

More Science and technology

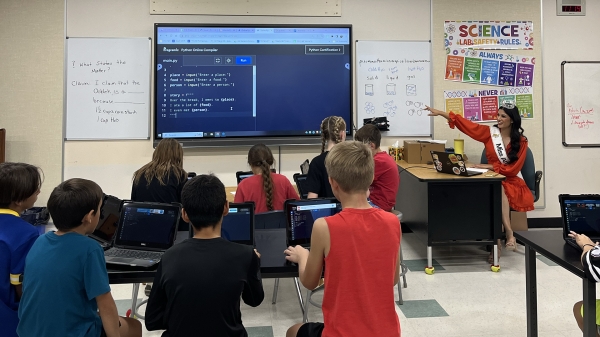

Miss Arizona, computer science major wants to inspire children to combine code and creativity

Editor’s note: This story is part of a series of profiles of notable spring 2024 graduates. “It’s bittersweet.” That’s how Tiffany Ticlo describes reaching this milestone. In May, she will graduate…

ASU applied behavior analysis program recognized in Four Corners region

Helping students with learning disabilities succeed in school and modeling effective communication skills are just two examples of how applied behavioral analysis improves lives. Since launching…

Redefining engineering education at West Valley campus

Editor's note: This story originally appeared in the summer 2024 issue of ASU Thrive magazine. What makes the School of Integrated Engineering different from other engineering schools? We listened…