Tempe names ASU’s Lester as MLK award recipient

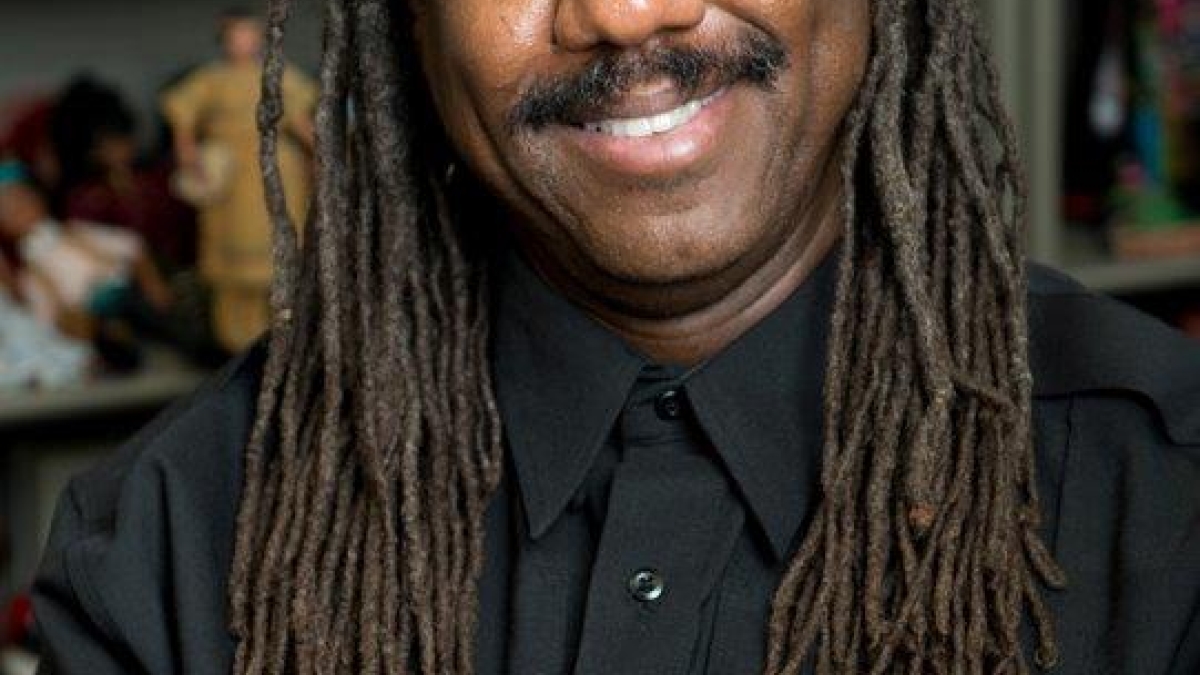

ASU professor Neal A. Lester has won several awards and recognitions throughout his academic career, and on Martin Luther King Jr. Day he’ll receive one that ranks right near the top.

The city of Tempe has announced that Lester will be given an MLK Diversity Award by the municipality’s Human Relations Commission for his commitment to diversity.

“Dr. Lester’s work in race relations, empathy and workplace training creates a more welcoming and inclusive environment, not only at ASU but throughout our Tempe community,” said Ginny Belousek, city of Tempe diversity manager. “His belief that culture and difference should be acknowledged, valued and celebrated is a shared vision with our city.”

The annual award is given to individuals, groups or organizations that best exemplify the spirit of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Lester, who is an ASU Foundation Professor of English and the founding director of the Project Humanities initiative, is one of nine recipients who will be honored at a Jan. 16 breakfast at the Tempe Marriott at the Buttes Resort.

Lester founded Project Humanities in 2010 at a time when humanities programs were being cut from school curricula. Since then he has demonstrated the rapidly growing success and impact of the ASU initiative with cultural workshops, community outreach and bias training in the workplace.

Lester spoke to ASU Now about his views on diversity and race, and how there’s still much work to be done in Arizona.

Question: Your most recent award is named after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Do you have a strong memory of King, or is there a speech or action he took that resonates with you?

Answer: I was a young child during the height of Dr. King’s activism work. I do, however, remember people around me being very sad when he was shot and killed. I have taught his speeches over the years, and his messages of equality, equity still resonate today in this country, particularly when we try and figure out the best way to resist oppressions non-violently.

There’s an urgency that people don’t always read when talking about Rev. King’s life work and the legacy he left behind.

Many have a tendency to think, “Change comes slowly.” Then I ask them to look at his “I Have a Dream” speech, and we then talk about the urgency and quiet impatience in his words about waiting too long and being tired of being treated like second-class citizens.

Yes, I am most taken by the urgency that we don’t often read when we look at his work.

Q: The MLK holiday evokes particularly strong feelings in Arizona given its history: The holiday was rescinded in 1987, but reinstituted in 1992. How far have we come as a state in terms of race and diversity since then?

A: I grew up in the Southeast and did most of my studies in the South, including graduate school in Nashville.

This whole notion of coming to the Southwest was interesting to me because when I made the decision to leave the Deep South to come to Arizona in 1997, people kept asking, “Why do you want to go to Arizona? They don’t even want to honor the MLK holiday.”

I know that’s one of those images and heritages that’s hard to shake off like Alabama and the firehoses and dogs attacking protesters and George Wallace standing in the door at the University of Alabama to prevent racial integration of the very school at which I was first tenured.

In my first KJZZ radio interview upon arriving in Arizona and being asked to talk about being black in this state, I described my experience as “bringing moisture to the desert” because it was a very different place than Birmingham, Alabama, where there was and is a greater black presence and also a greater African-American presence in terms of those in government and other policymaking positions.

I was pleasantly surprised to find here, however, a vibrant and growing Black Theatre Troupe, something I hadn’t seen in Birmingham.

In my classroom, I had a bizarre set of questions coming to me from white students at ASU who would say the things that most people would never dare to say in Alabama. For example, a white student commented with grave concern that she “didn’t know how she would do in my African-American literature survey course because she hadn’t been around a lot of black people.”

That was very strange to me on a couple of levels, and so there’s still this narrative today, which is, “Why are you still in Arizona since there are so few black people there? There are brown people, but not black people.”

As to how much progress blacks in Arizona have made, I’m not one to oversimplify or to uncomplicate: I think we can’t look at one group without looking at another group in terms of social justice issues related to black and brown folks in Arizona. We have to talk about racial profiling, and we have to talk about immigration.

When I first came here, I distinctly recall an Arizona Republic headline reading something to the effect of, “If you have brown skin and speak Spanish, your civil rights can be violated.”

So while there have been no dogs biting and firehoses put on people, brown and black and LGBTQ people are still being treated inhumanely and discriminated against.

This, sadly, is not just a local or regional problem. The whole sense of divisiveness and raw and unadorned incivility and unkindness underscores a national concern, especially now as we move into a new presidential term.

Q: What is your definition of the word “diversity,” and how should it be applied?

A: Rather than define it, I’d rather approach the notion of “diversity” in a different way.

Diversity is such as loaded word that often translates to people in different ways. Then it translates first to race and then gender.

To me, what is more meaningful than cultural potlucks, heritage months and diversity weeks is to talk about inclusion — the ways in which we all have unconscious biases and how those biases and systems of privilege play out every day and everywhere.

If we could find our shared humanity and start looking through the lens of what our award-winning Project Humanities university initiative calls Humanity 101 — compassion, empathy, forgiveness, integrity, kindness, respect and self-reflection — then there’d be no need to have a focus on “diversity” per se because people would be respecting each other whether you are able-bodied, able-minded, atheist, trans* or cis*, or overweight.

To me, the notion of diversity is not just one or two things, it’s about looking at our identities from an intersectional perspective.

We can’t talk about race without talking about gender, class and religion, for instance.

That’s what to me has been missing from the more traditional conversations about diversity.

When we talk about diversity, it’s not ever just about race or just about one part of our intersecting identities. When we talk about diversity, we have to recognize that we’re all members of multiple communities simultaneously, and it depends which community needs our attention at the time.

It means we don’t exist as a single thing.

I think this line of thinking opens up the conversation to where non-people of color don’t feel dumped on and then people of color don’t feel like we have to continually educate.

There is a thing I have come to call “racial fatigue.” Over the past couple of years with police shootings and other racially charged happenings in this country, I teach about race in my classes, I write and publish about race, I live in a society where race is brought up, but every single moment of my life is not focused on race.

When I sit down to dinner, I don’t focus on race. Anything that’s on the television, anything on a magazine or the radio can, however, signal race, so there’s no reason to avoid conversations about race, sexuality or gender, or think our social problems around these various systems of privilege go away if we stop talking about them and thinking about them.

Finally, I’ll say I get discouraged when I hear people say we talk too much about race; as though somehow not talking about race, it would make the problem go away.

That’s like saying if we stop talking about our cancer, somehow it will go away. I don’t measure progress in terms of how many heritage months we have, but how people are treated, even when you’re sitting at the proverbial table of opportunity.

Q: The world has definitely become a more diverse place, but it seems as if there’s a push and pull, one step forward, two steps back feel to things. Do you see it that way?

A: We have come to understand diversity in more complex ways, so we don’t necessarily think of diversity in one way.

If we were to say, “There’s been no progress,” which by the way, I would never say, I would say, “That’s not true.” We don’t have the same Jim Crow laws, but we still have the segregation economically and racially in Arizona and across the country.

We don’t have bodies hanging from trees as in Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit,” but we certainly have a disproportionate number of black males in prison and being shot in the streets unarmed than we do other folks.

Yeah, we’ve come a long way, but we can’t pat ourselves on the backs and say there’s still not a lot of hard work to be done. That’s what people still need to recognize. We’ve still got to work ahead of us, and that’s where my emotional and political fatigue comes in.

Q: You have this gift for getting all the parties to listen without pulling any punches in your message. What is it that you want people to come away with whenever you are asked to speak on diversity?

A: I actually do try to pull punches, but not in a way that’s shocking. I try to get people to think in ways they haven’t thought before.

For example, if we’re talking about the N-word, I want to get people to recognize that if you change the ending of the word, you do not actually change the meaning of that word. So my punch comes in pointing out that the “a” version of the N-word was used in Minstrel songs, in children’s books, in selling commercial ads.

That’s the punch, but it comes from having done the research. I don’t come in and try and punch people by lecturing or sermonizing to them. I try instead to engage them to help move them toward the same kind of discovery I experience when digging beneath the surface of these complex topic and ideas.

I say, “Here’s what I’ve been doing, let me show you what I’ve found. Is there anything you’ve learned now that you’ve heard what I have to offer?”

So, I’m always looking for ways to start a critical conversation with people from the point of what they already know, then go into what they want to know, then ask if they’ve learned anything … just one thing from their experience with me in these formal settings in the process.

I always try to come away asking, “Well, what did I learn from the same experience about myself, about other people, and about the subject I am presenting?”

That’s why teaching is so exciting to me, because even though I have a general script or text to teach, I never know how the audience is going to react. In the end, this diversity work reminds me daily that “we actually are more alike than we are unalike,” as poet Maya Angelou has pronounced.