Leonard Cohen was never supposed to be a huge star. He was a failed poet and novelist before he tried his hand at songrwiting. He didn’t have the best voice, and for years he couldn’t sing or play the guitar.

But when he died last week at the age of 82, the critics, the entertainment world and fans mourned his loss.

The Canadian folk singer-songwriter never produced a Top 40 single or album on his own, or was considered a mainstream success. His fame came mostly through other musical artists who covered his songs, including Judy Collins, James Taylor, Joan Baez, Jennifer Warnes and k.d. lang.

His most significant work, 1984’s “Hallelujah,” was a fluke and originally rejected by his music label. It was eventually issued on a small indie label and landed with a thud. It took almost a decade for the song to find its audience, but when it did, the tune exploded. To date, “Hallelujah” has been covered by more than 300 artists in various languages and featured in film (“Shrek”) and television soundtracks (“The West Wing”) as well as televised talent contests, helping him to ride a wave of rediscovery. (It also was performed this past weekend by Kate McKinnon on "Saturday Night Live.")

Cohen’s status as the ultimate cult artist made him a symbol of resilience and productivity, which is how he earned a place in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, the Canadian Music Hall of Fame and the Canadian Songwriters Hall of Fame.

ASU Now spoke with Peter Lehman, a professor in film and media studies in the English department and the director of the Center for Film, Media and Popular Culture, to discuss Cohen’s odd but deeply impactful career and what he hopes his legacy will not become.

Question: How would you describe Leonard Cohen’s music and recording career?

Answer: Leonard Cohen is frequently thought of as a cult figure in part because he was never primarily a Top 40 singles artist. Many people knew his recording of “Bird on a Wire,” but most of his other songs became known in cover versions. The public often only knows who sings songs, not who wrote them. Secondly, he was frequently referred to as a “poet.” Although intended as a compliment, I think this is always a mistake in popular music, a disservice to musicians and poets. Cohen, of course had been both a poet and novelist prior to becoming a musician, and this may have even further muddied the water.

Q: Cohen tried his hand at almost everything — poetry, novels, music — but his impact on film and television seems like his biggest legacy.

A: The extensive use of Cohen's music in film and television throughout his career has played a major role in giving him high visibility, often with exactly the right audiences. And, as so often happens with movies, this exposure, even more than hit singles at the time of release, brings the music to the attention of new generations of young people who become fans. In 1971, Robert Altman used four Cohen songs in his critically acclaimed and commercially successful revisionist Western, “McCabe and Mrs. Miller.” Altman became an almost heroic figure to a generation of film critics and students for his independent, innovative filmmaking, and “McCabe and Mrs. Miller” retains its classic status to this day for critics, film fans, and film students, continuing to bring attention to Cohen.

In recent years, Cohen's music has been featured in innovative, challenging television series: “Nevermind” was used over the credits of Season 2 of “True Detective” (2014), and “You Want It Darker” was used to startling effect in an episode of Season 3 of “Peaky Blinders” (2016) prior to its CD release. These shows are edgy and push musical boundaries.

Q: Did you ever see him perform in concert, and if so, what was that experience like?

A: I saw Cohen live on his rightly famous World Tour in Phoenix on April 5, 2009, at the Dodge Theatre (now Comerica Theatre). It was one of the greatest concerts of my life, in a league with Roy Orbison, Merle Haggard, Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen. He was 74 years old but at the peak of his powers and with the energy of someone half that age. It was a musically nuanced and sophisticated performance.

I mention in my book, “Roy Orbison: The Invention of an Alternative Rock Masculinity,” that Cohen was a big admirer. On his 1998 tour, during rehearsals Cohen told the musicians, “Make it like Roy Orbison would do it,” and the musicians joked about “Orbisizing” the songs. Cohen even had a photo of Roy Orbison pasted into their chart folders. Cohen was in the audience at the filming of the now-famous “Roy Orbison: Black & White Night” concert in 1987 and Jennifer Warnes, a close collaborator at the time, sang as one of the female backup singers. Obviously, Roy Orbison wrote and sang songs much, much different than Cohen, who knew and cared deeply about a wide range of music.

Q: Cohen’s best-known song, “Hallelujah” is more than 30 years old and still has magic attached to it. Why does the song continue to matter?

A: The best way I can answer this question is by giving you an anecdote. I’ve seen k.d. lang in concert several times. The first two times the one song that brought down the house and where she received a standing ovation was her cover version of Roy Orbison’s “Crying.” At one point she replaced that with Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah,” and that became the song that brought down the house down and garnered a standing ovation. I’ve experienced the extraordinary power of that song when other artists have covered it.

It has an amazing power and beauty and has an intangible quality. When someone sings it, they can make it their own. For me, the magic of the song is how it inspires other artists to do their very best work, and it is unquestionably a phenomenon.

Q: How should Cohen be remembered or not remembered?

A: There has been a movement to elevate rock and country music stars into poets by their estates, the academic and literary world and even the Nobel Prize Committee. What is happening here has a parallel with what happened in English and language departments when film initially entered the curriculum in the late '60s and '70s. There was an effort to legitimize the study of film by overemphasizing its connection to the written word via adaptations of classic novels and by elevating screenplays with “literary” quality that could be read. With music, the emphasis has been on poetry, not novels or plays. Academics are trained in and used to analyzing words. It has been an ongoing process to learn how to analyze the complex sights and sounds of film construction without reducing style to a form of window dressing. Scholars of rock and roll and country music have not yet caught up with film studies in that regard. Johnny Cash is a significant American musician. Despite a recent “New York Times” article dubbing him the "poet in black" and his estate claiming him as a significant American literary figure, his new book of poetry will undoubtedly be minor at best in comparison.

I have tremendous respect for literature and poetry, I read literature every day of my life … but when it comes to these art forms such as movies and popular music, we put too much emphasis on words when we extract them from their context and, with songs, expect the lyrics to bear the weight of the meaning as it were. Leonard Cohen was an outstanding lyricist, but by calling him a “poet,” it distorts his skill as a singer/songwriter/concert performer. He will be deeply missed as a musician.

More Arts, humanities and education

'Devils in the Metal': ASU vet leads iron cast workshop for former service members

Bruce Ward believes everyone has a symbol of strength or resilience, and they have an obligation to find it. His happens to be a paper crane in an ocean wave. “It’s the idea that we are the…

ASU English professor wins Guggenheim Fellowship for poetry

The awards — and opportunities — keep piling up for Safiya Sinclair, an associate professor in Arizona State University’s Department of English. In mid-April, Sinclair received one of 188 Guggenheim…

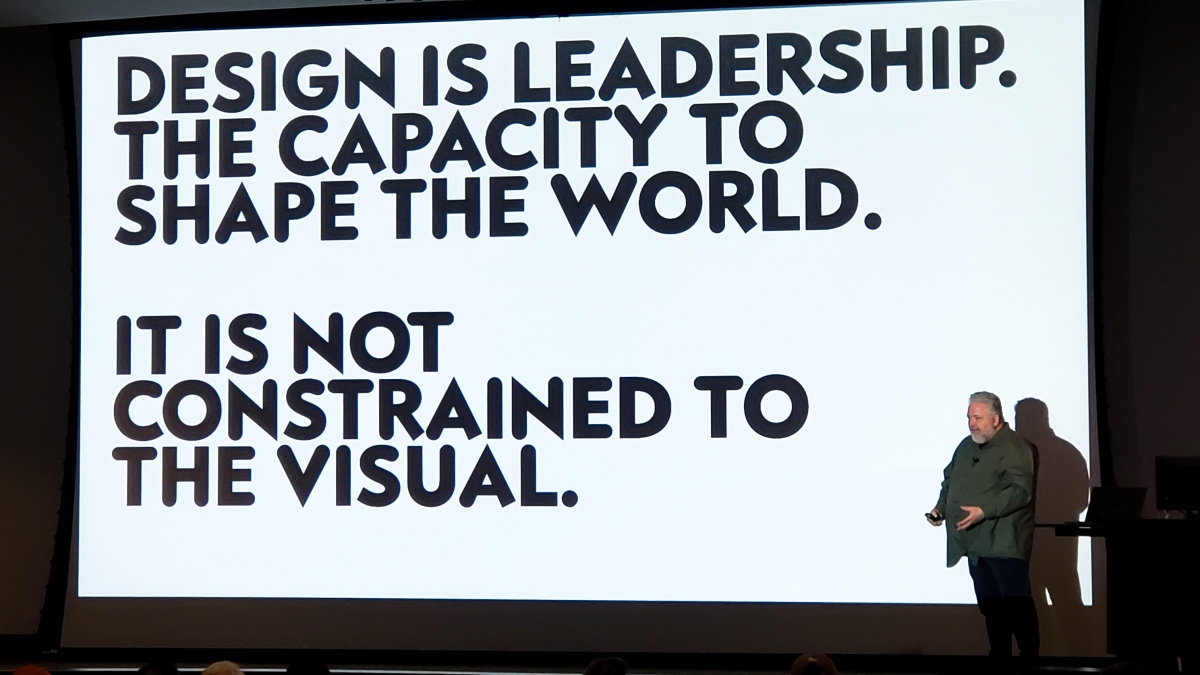

Designer behind ASU’s brand named newest Herberger Institute Professor

Bruce Mau, co-founder and CEO of the Chicago-based holistic design consultancy Massive Change Network, has joined Arizona State University’s Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts as its newest…