New research sheds light on ‘gender gap’ in cystic fibrosis

ASU researcher part of team examining the underpinnings of lethal disease

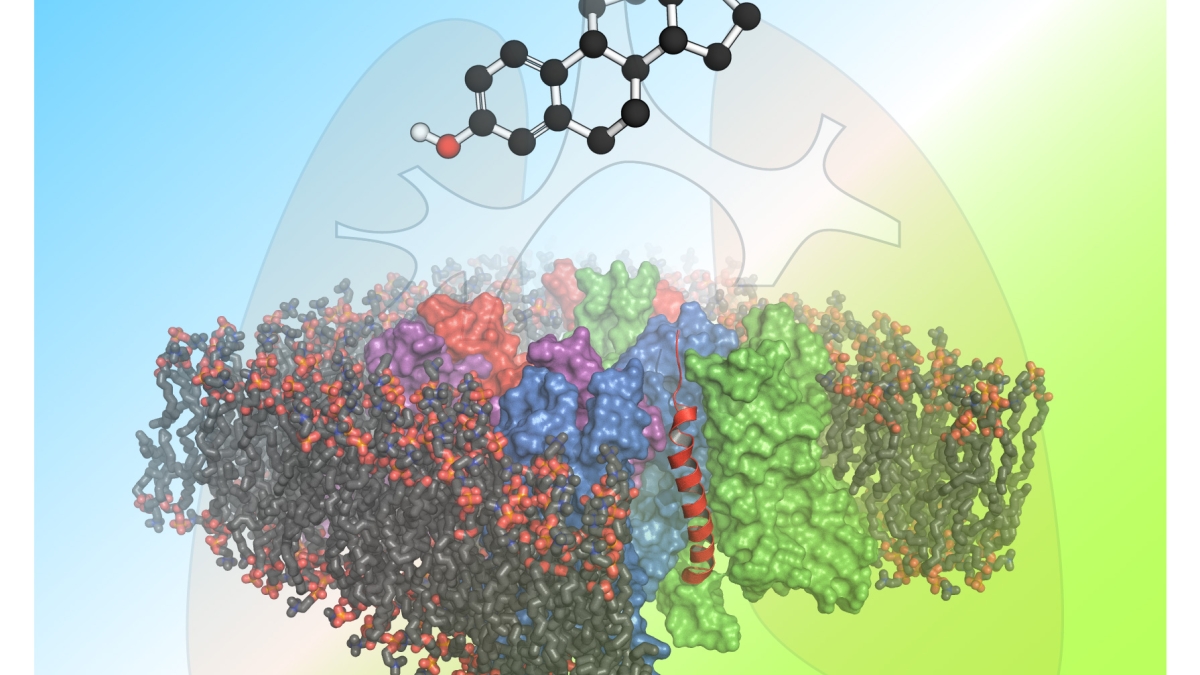

Estrogen (black and red molecule: top of diagram) can exacerbate the effects of cystic fibrosis in women, accounting for a gender gap in disease severity and lethality. The large, multicolored image overlaying the lung is the membrane protein KCNQ1, which acts as a channel for ion flow. A modulator protein KCNE3 (seen in bright red) docks and forms a complex with KCEQ1, causing the ion channel to stay in an open position and allowing the unimpeded flow of ions. The presence of estrogen can disrupt this ion channel, causing a buildup of fluid in epithelial tissue and increasing susceptibility to bacterial infection in cystic fibrosis patients.

A minor hiccup in the sequence of a human gene can have devastating impacts on health. Such flaws cause cystic fibrosis, a disease affecting the lungs and other vital organs, often leading to death by the age of 30.

In new research appearing in the current issue of Science Advances, Arizona State University researcher Wade Van Horn and his colleagues from Vanderbilt and Northwestern Universities examine the underpinnings of this deadly affliction, including its apparent disproportionate effect on women, which is due in part to the influence of estrogen on the flow of important chemical ions.

The research offers new insights into the underlying mechanisms that affect the disease and sets the stage for development of new treatment strategies aimed at preventing or reversing its calamitous effects.

Van Horn is a researcher at ASU’s Biodesign Center for Personalized Diagnostics. In the current study, a multi-university group explores a crucial protein involved in the transport of ions across biological membranes.

Cellular internet

The transport of ions is a vital feature of living systems, allowing a range of physiological processes including heartbeat, hearing and muscle movements. Defects in ion transport are implicated in a broad range of serious diseases, including cholera, pulmonary edema and cystic fibrosis.

“One of the most common ways for cells to communicate is through the flux of ions like sodium, potassium and magnesium. Ion channels are effectively holes in the membrane that are tightly regulated — they're protein-based,” Van Horn said.

The ion transport system investigated in the current research involves a critical protein known as KCNE3, which helps properly regulate ion transport. KCNE3 forms a complex with a partner protein — KCNQ1, which acts as a channel for ions. Together, they form a finely tuned gateway, permitting or blocking ion transport in order to maintain salt and fluid homeostasis.

The KCNE3-KCNQ1 complex is described in the new study with unprecedented clarity using a combination of experimental data, molecular dynamics, evaluation of similar proteins across species and sophisticated predictive modeling of protein structure.

Among its many functions, KCNE3 regulates the flow of potassium (K+) ions which impact transport of chloride (Cl-) ions across epithelial tissues. In patients with cystic fibrosis, the efficient migration of chloride ions is impaired. The research provides new insights into the proper functioning of the chloride ion gateway and mechanisms underlying its dysfunction in patients with cystic fibrosis.

“This is an unusual case in biology where this accessory membrane protein binds to the ion channel and effectively turns the ion channel on. That’s important especially in the trachea and epithelial tissues in your lungs,” Van Horn said.

A better understanding of the structure and function of the ion gateway reveals how estrogen might interfere with the KCNE3-KCNQ1 channel complex, apparently worsening the effects of cystic fibrosis lung disease and leading to higher mortality rates and a shorter lifespan for female patients.

“The focus of this study is to understand how this KCNE3 protein interacts with the ion channel KCNQ1 and how KCNE3 causes the channel to become fully open, or conductive, to ion flow,” Van Horn said.

James Zook pictured at ASU's Magnetic Resonance Research Center. Researchers like Wade Van Horn of the Biodesign Institute use the facility to investigate the structure and dynamics of membrane proteins. Photo courtesy of Biodesign Institute

By combining a variety of experimental approaches including structural biology, electrophysiology, cell biology and computational biology, the study reveals the detailed workings of the membrane protein complex, using the predictive power of structural biology to see how estrogen may influence the disruption the channel.

Among the tools used for these investigations is nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), a technology closely related to the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) now common in clinical settings for observing tissues and organs in the body with high resolution.

NMR exploits the magnetic properties of atomic nuclei, allowing researchers like Van Horn to zero in on structural details of biomolecules (including membrane proteins) with remarkable clarity. Using the technique, scientists are able to predict the effects of certain mutations on protein structure and dynamics and optimize drug interactions with target proteins.

Lethal glitch

Cystic fibrosis is a genetic disorder whose primary effect is on the lungs, though the pancreas, liver, intestines and kidneys may also be damaged. The disease is most common among people of northern European ancestry and strikes roughly one of every 3,000 newborns.

The disorder is known as an autosomal recessive disease, meaning that both parental copies of a particular gene must contain a mutation, resulting in an aberrant form of a protein known as the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR). Individuals with only one defective copy of the gene are generally disease-free, but may act as carriers of the recessive trait.

The most common defect leading to cystic fibrosis is a deletion of three nucleotides coding for the amino acid phenylalanine, though some 1,500 other mutations can also produce cystic fibrosis. Alternate mutations cause differing effects on the CFTR protein, sometimes causing milder or more severe manifestations of the disease.

It is generally recognized that females are more susceptible to the ravages of cystic fibrosis, often displaying more severe symptoms and shorter life expectancy. The hormone estrogen is believed to be a crucial contributing factor to the observed gender gap in cystic fibrosis cases.

Disruption of ion flux accounts in part for symptoms of cystic fibrosis, which include the ramped-up production of sweat, mucus, and digestive fluids. The condition remains incurable. The vast majority of cystic fibrosis patients die from bacterial infections, particularly from the pathogen pseudomonas.

It is believed that proper functioning of the KCNQ1 channel helps mitigate fluid buildup in the lungs. When inhibited by high concentrations of estrogen, ion flow is impaired, allowing bacterial infections to take hold. Around 80 percent of the deaths caused by cystic fibrosis are the result of lung problems. Serious infections caused by the disease are typically treated with antibiotics, which have somewhat improved the prognosis for cystic fibrosis patients, though the disease remains a leading killer.

A number of telltale symptoms are characteristic of cystic fibrosis and include salty-tasting skin, poor growth and poor weight gain, and the accumulation of thick, sticky mucus. The patient is often short of breath, and bacterial chest infections are common.

Such symptoms typically appear in infancy and childhood. Failure of proper growth may be due to a combination of factors, including chronic lung infection, poor absorption of nutrients through the gastrointestinal tract, and increased metabolic demand as a result of chronic illness.

Form and function

As Van Horn emphasizes, membrane proteins, like those examined in the current study, account for nearly a third of all human proteins and are key factors in health and disease. Such proteins are targets of the vast majority of drugs and other therapeutic agents, yet a more thorough understanding of their detailed structure and subtle interplay is necessary before cystic fibrosis and a host of other protein-based diseases may be adequately addressed.

“This is really the golden era for the field of membrane protein structural biology. We are starting to really understand how these proteins are working together and what the architectures look like,” Van Horn said. “In the long term, a better understanding of how membrane proteins work will help to make cystic fibrosis and other diseases more easily treatable.”

Van Horn is an assistant professor in the School of Molecular Sciences.

More Science and technology

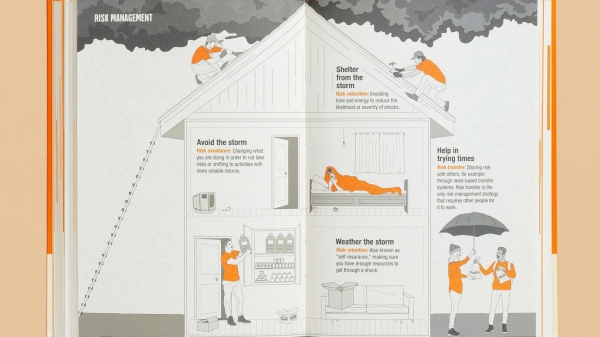

ASU author puts the fun in preparing for the apocalypse

The idea of an apocalypse was once only the stuff of science fiction — like in “Dawn of the Dead” or “I Am Legend.” However…

Meet student researchers solving real-world challenges

Developing sustainable solar energy solutions, deploying fungi to support soils affected by wildfire, making space education more…

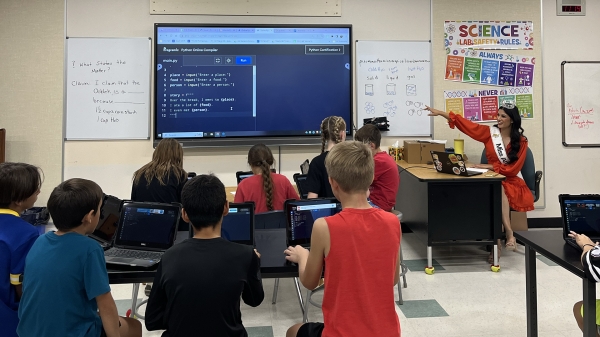

Miss Arizona, computer science major wants to inspire children to combine code and creativity

Editor’s note: This story is part of a series of profiles of notable spring 2024 graduates. “It’s bittersweet.” That’s how…