Mars rover Curiosity makes first gravity-measuring traverse on the Red Planet

ASU graduate student is on a team that found Mars rocks less compacted, more porous than scientists expected

A clever use of nonscience engineering data from NASA's Mars rover Curiosity has let a team of researchers, including an Arizona State University graduate student, measure the density of rock layers in 96-mile-wide Gale Crater.

The findings, to be published Feb. 1, in the journal Science, show that the layers are more porous than scientists had suspected. The discovery also gives scientists a novel technique to use in the future as the rover continues its trek across the crater and up Mount Sharp, a three-mile-high mountain in its center.

"What we were able to do is measure the bulk density of the material in Gale Crater," said Travis Gabriel, a graduate student in ASU's School of Earth and Space Exploration. He worked on computing what the grain density should be for the rocks and ancient lakebed sediments the rover has been driving over.

"Working from the rocks' mineral abundances as determined by the chemistry and mineralogy instrument, we estimated a grain density of 2810 kilograms per cubic meter," he said. "However, the bulk density that came out of our study is a lot less — 1680 kilograms per cubic meter."

The much lower figure shows that the rocks have a reduced density, most likely resulting from the rocks being more porous. This means the rocks have been compressed less than scientists have thought.

Like a smartphone, but better

The engineering sensors used in the study were accelerometers, much like those found in every smartphone. In a phone, these determine its orientation and motion. Curiosity's sensors do the same, but with much greater precision, helping engineers and mission controllers navigate the rover across the Martian surface.

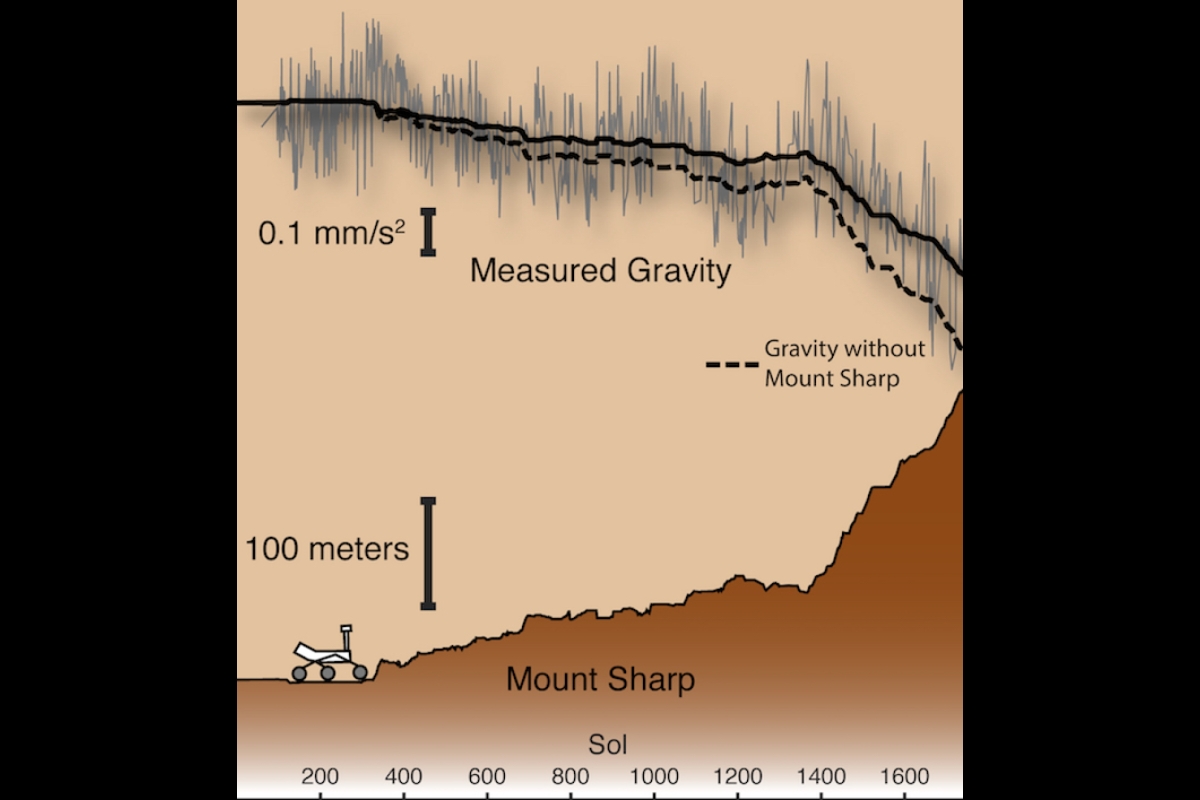

But while the rover is standing still, the accelerometers also measure the local force of gravity at that spot on Mars.

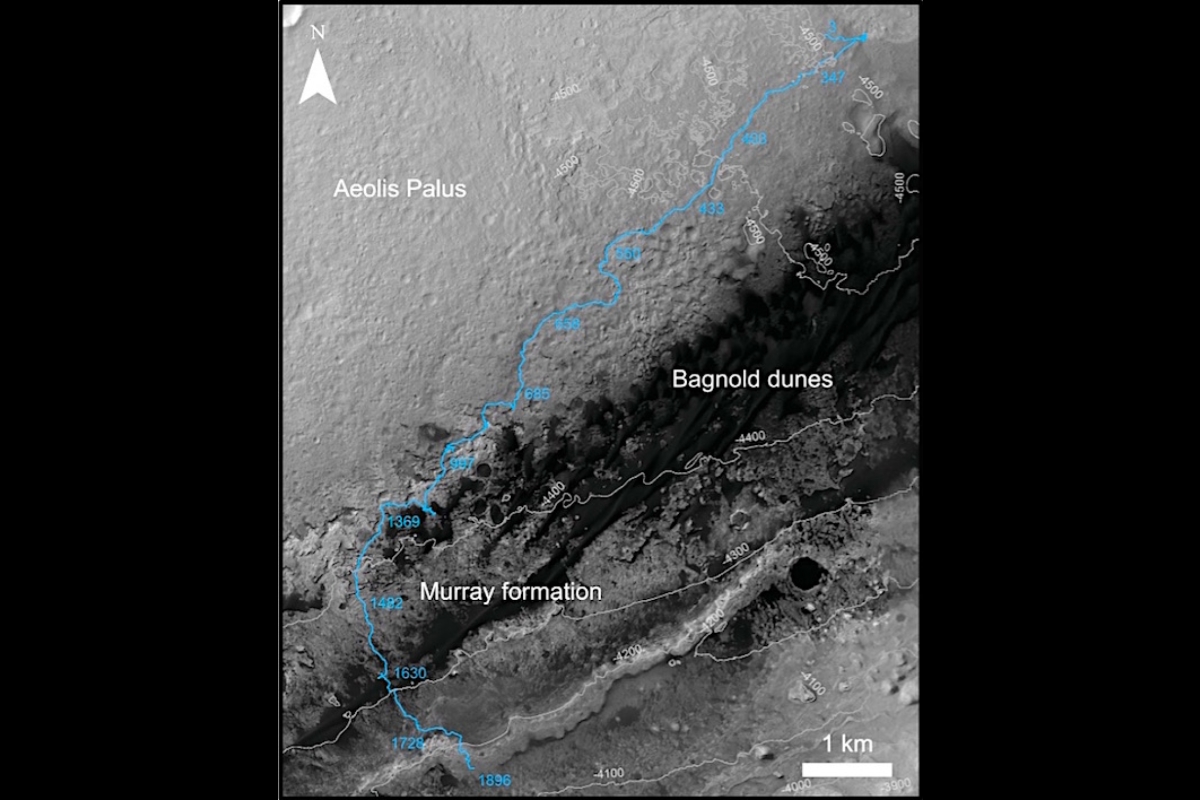

The team took the engineering data from the first five years of the mission — Curiosity landed in 2012 — and used it to measure the gravitational tug of Mars at more than 700 points along the rover's track. As Curiosity has been ascending Mount Sharp, the mountain began to tug on it, as well — but not as much as scientists expected.

"The lower levels of Mount Sharp are surprisingly porous," said lead author Kevin Lewis of Johns Hopkins University. "We know the bottom layers of the mountain were buried over time. That compacts them, making them denser. But this finding suggests they weren't buried by as much material as we thought."

Making Mount Sharp

Planetary scientists have long debated the origin of Mount Sharp. Mars craters the size of Gale typically have central peaks raised by the shock of the impact that made the crater. A central peak would account for part of the mound's height. But the uppermost layers of the mound appear to be made of wind-scoured sediments more easily eroded than rock. Where did they come from?

And did these sediments once fill the entire bowl of Gale Crater? If so, they might have weighed heavily on the materials at the base, compacting them.

But the new findings suggest Mount Sharp's lower layers have been compacted by only a half-mile to a mile (1 to 2 kilometers) of material — much less than if the crater had been completely filled.

"There are still many questions about how Mount Sharp developed, but this paper adds an important piece to the puzzle," said Ashwin Vasavada, Curiosity's project scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, which manages the mission. "I’m thrilled that creative scientists and engineers are still finding innovative ways to make new scientific discoveries with the rover."

Gabriel added, "This is a testament to the utility of having a diverse set of techniques with the Curiosity rover, and we’re excited to see what the upper layers of Mount Sharp have in store."

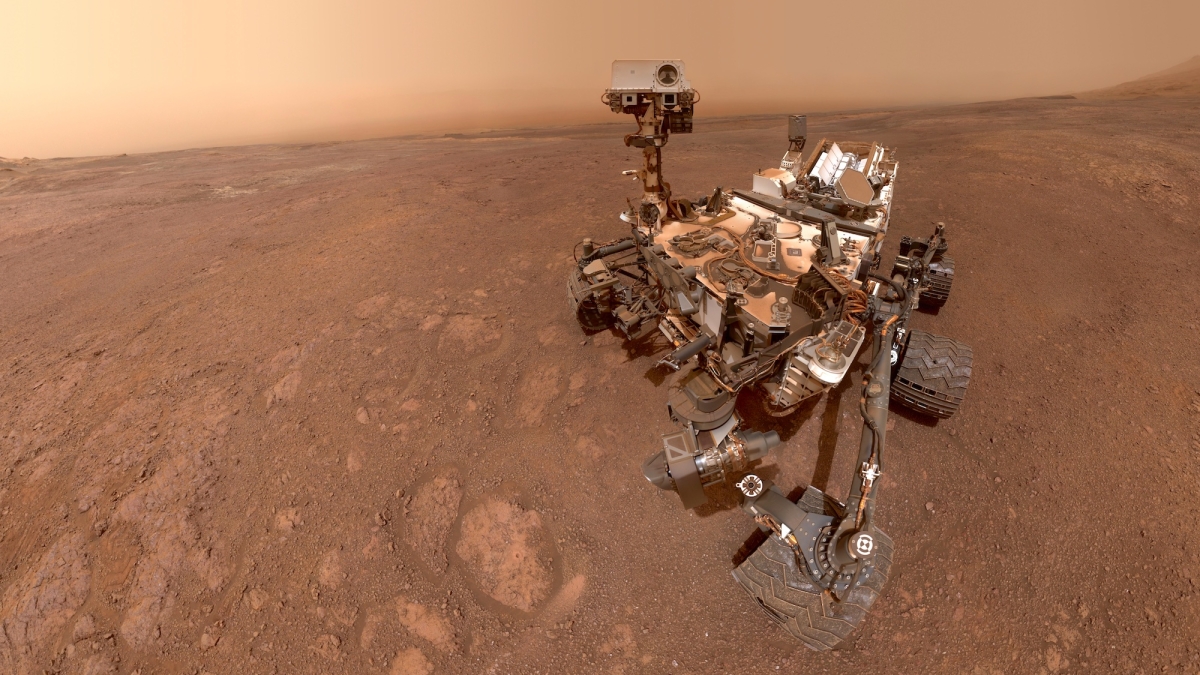

Top photo: In a selfie taken in mid-January 2019, Mars rover Curiosity prepares to enter a new, clay-mineral-rich unit on its traverse up Mount Sharp in Gale Crater. Mission scientists are anxious to see what a new gravity-measuring technique will reveal about the mountain and Gale Crater's history. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS

More Science and technology

Securing the wireless spectrum

The number of devices using wireless communications networks for telephone calls, texting, data and more has grown from 336 million in 2013 to 523 million in 2022, according to data from U.S.…

New interactive game educates children on heat safety

Ask A Biologist, a long-running K–12 educational outreach effort by the School of Life Sciences at Arizona State University, has launched its latest interactive educational game, called "Beat the…

Unlocking Earth's origins

Looking up at a vast, star-studded sky, people have always wondered: Are we alone in this universe? It’s a fundamental question that has intrigued and inspired curious minds across all corners of…